ROM’s Curator of Fishes on the origins of his 19-year partnership with contemporary artist David Brooks

Few moments in my life have been so disheartening.

After weeks of arduous travel by plane, truck, boat, and foot, I had reached the top of Salto de Oso, a remote, rainforest-shrouded waterfall near the Brazilian-Venezuelan border. But the discovery I hoped to find—a missing link in the 100-million-year history of fishes in northern South America—would remain maddeningly beyond my grasp.

I was a third-year PhD-student and this was already my fifth expedition to wildernesses of the Guiana Shield, a rugged, biodiverse, and geologically ancient plateau spanning the northern South American frontiers of Venezuela, Brazil, and Guyana. I sat by the edge of the falls, with oceanic waves battering rocks at my feet and surging over the falls. My heart sunk upon realizing that I had arrived weeks too late. The rains had arrived before I expected, and with the wet season well underway, the río Siapa—a remote blackwater river populated only by a few dozen Yanomami Indigenous communities—was far too deep and turbulent to even consider sampling with any form of hook, net, or trap. Soaked and covered in blackfly bites, my only solace was the serene glimpse of a red howler monkey leaning to drink in the mist of the opposite bank, blissfully unaware of a graduate student’s despair at having spent tens of thousands of their advisor’s grant dollars with nothing to show for it.

Unbeknownst to me then, my doomed expedition would soon take a dramatic turn for the better. On a rock in the middle of the nearby Casiquiare Canal, I would meet a contemporary artist and naturalist who would become one of my most enduring, life-long collaborators.

Only two years before, I had entered the PhD program in Auburn University’s Department of Biology under the supervision of Dr. Jonathan W. Armbruster. I was driven by a passion to discover and describe new Amazonian fish species, reveal their ecological and evolutionary relationships, and extract from them a greater understanding of the history of life on Earth. I could hardly have found a better lab in which to indulge these passions. My advisor and four colleagues had just been awarded a five-year, $5-million grant from the US National Science Foundation (NSF) to discover and describe all species of the globally distributed fish order commonly known as catfishes. This was part of a revolutionary new series of NSF grants called Planetary Biodiversity Inventories, which sought to accelerate the discovery and description of life’s richness in the face of humanity’s accelerating destruction of habitats that many species need to survive. With this support from NSF, I made nine collecting expeditions to five countries in a brief five-year window of graduate school.

At the climax of the fourth of these expeditions, on the afternoon of April 21, 2004, I made a discovery that still shapes my strategy for exploring the Guiana Shield. Under a bright mid-day sun, my Venezuelan colleague Oscar Leon Mata and I became the first scientists to sample fishes from the top of Salto Tencua, another southern Venezuelan waterfall that interrupts the río Ventuari about 300 km to the north-northwest of Salto de Oso. All the fishes we collected that afternoon were different from the species we had collected just downstream of the falls, and most were new to science. Preliminary morphological features, later supported by genetic research, indicated that some of their closest relatives lived in other drainage basins thousands of kilometers away, sometimes on the opposite side of the Guiana Shield plateau. The immediate implication was that over millions of years, the slow and intermittent geologic uplift of the Guiana Shield plateau itself, which had created the waterfalls, had also isolated fish populations and contributed to the diversification of life across this region. I was compelled to test this hypothesis, and for that I would need another river, and waterfall, draining the Guiana Shield. After scouring maps of southern Venezuela, I identified Salto de Oso in far southern Amazonas State as a promising place to find more such relictual fish species.

One of the challenges to planning a major expedition spanning the seven-weeks required to reach and return from Salto de Oso by boat is finding experienced and stalwart companions willing and able to take weeks away from their jobs. Fieldwork in southern Venezuela is virtually impossible today, given the country’s economic and political turmoil, but it has always been challenging. The upper Orinoco River, which is the main transportation corridor, demarcates a border with Colombia that was then militarized by the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC). Just a couple years before, an American businessman visiting the region to fish for peacock bass had been kidnapped by FARC and held for ransom. There were also insect-borne diseases, such as leishmaniasis, chagas, and malaria, not to mention the giant Orinoco crocodiles that still guarded some of the same remote habitats we sought to sample.

One top candidate who I started recruiting for this trip was Mike Gangloff, a close friend and freshwater mussel biologist who was then a member of my doctoral cohort and is now faculty at Appalachian State University. On my 2004 trip to the upper Orinoco, I had also discovered an abundant, small, encrusting mussel near the mouth of the Ventuari that Mike and I would later describe as a new genus in the zebra mussel family Dreissenidae. Mike was a seasoned field biologist who had spent years descending rivers throughout the southeastern US, and I hoped he would help me investigate this new bivalve. He demurred, though, needing to focus on his dissertation, and recommended that I instead contact David Brooks, an aspiring sculptor with whom his sister, acclaimed American painter Hope Gangloff, had attended the prestigious Cooper Union college.

I at first laughed off this suggestion. As a PhD student immersed in the esoteric minutiae of fish taxonomy and the ancient geologic history of South American rivers, I saw little value in inviting an artist to join me.

Mike persisted though. He, Hope, and Brooks had frequently fished South Oyster Bay from the Gangloff family home on Amityville, Long Island. Not only was Brooks an artist, Mike assured me, he was an avid fisherman, birder, and naturalist who would do anything, including cover his own expenses, to join me.

With time running out, and the list of potential scientists getting shorter, Brooks became a top candidate for my B-team, which would replace three A-team scientists when they flew out after the first four weeks of the expedition. Given my tight budget, Brooks’ willingness to cover his expenses became the deciding factor.

So, I gave him a call. If he could arrive on a given day and time at the small airport of Puerto Ayacucho, capital of Venezuela’s Amazonas State, he could fly in to meet me on the same small plane I had chartered to extract my A-team.

The days following my howler monkey encounter at the top of Salto de Oso were depressing and stressful. Blackflies plagued the team from dawn to dusk, the weather was rainy and cool, and team dynamics were deteriorating. As trip leader, I was preoccupied with the money and person-hours spent arriving at a remote destination yielding no significant discoveries. I felt responsible for the failure. When fishing is good, arduous field conditions are easy to endure. But when water levels are high and fishing is bad, those same conditions can be soul-crushing.

I had little reason to think that the replacement of my A-team scientists with an artist whom I only knew from a few phone calls might do anything to turn the trip around. So, in the Casiquiare Canal, my diminished crew and I awaited the B-team’s arrival. I had resolved that as soon as the new expedition team formed, I would instruct our boat captain—famed Curipaco riverman Colorado Santaella—to reverse course and head back up the Casiquiare and down the Orinoco to revisit old collecting sites in the lower río Ventuari, where I was confident the rains had not yet arrived and the fishing would be better. In the meantime, as we awaited the distant drone of an outboard motor, we had little to do but listlessly swat blackflies and clean and organize our gear, laundry, and 60-foot expedition boat: the Lupe Melys.

It was to this dispirited crew that Brooks and three colleagues—the B-team—arrived. True to Mike’s recommendations, Brooks was thrilled to finally meet up with us. Fresh and enthusiastic, the B-team immediately set to work fishing with hook and line, while I pulled up the gillnets in preparation for an early departure the next morning.

Buoyed by new perspectives and a new direction, our luck turned. We concluded our 2005 expedition with several fascinating and valuable discoveries, several of which I am still studying to this day. But what made the trip exceptional was the robust foundation it laid for an enduring collaboration that Brooks and I continue to explore 19 years later.

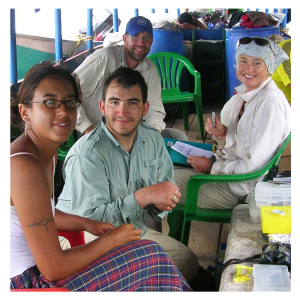

Brooks and Lujan in 2005, on their first expedition together to the upper Orinoco, with teammates Mariangeles Arce and Mayme Grant (right).

Since 2005, Brooks has joined me on seven other expeditions to Ecuador, Peru, and Guyana. He is now a professor at New York University’s Gallatin School and an internationally acclaimed artist, having won the Rome Prize in 2020 and exhibited in over twelve countries.

Most recently, Brooks and I collaborated on an art installation entitled Lonely Loricariidae, which ran from November 18, 2023 to April 7, 2024 at the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Bentonville, Arkansas, as part of their Enduring Amazon exhibition. Loricariidae is the scientific name of the suckermouth armored catfish family that has been the focus of my research since graduate school. The family contains over 1,050 species endemic to tropical Central and South America, 32 of which I have discovered and described as new to science. Hundreds of thousands of these fishes, dozens of which remain scientifically undescribed, are exported every year to supply the global trade in ornamental aquarium fishes.

Lonely Loricariidae engaged this trade to fill ten aquaria with a single wild-caught, undescribed loricariid species each. The aquaria were largely bare, except for a piece of driftwood, and sat atop aluminum sports bleachers as strangers might at a sparsely attended event. Encountered at eye level, the intriguing and varied fishes invite empathy and wonder, themselves becoming spectators of human allure. A goal of the piece is that these Amazonian emissaries penetrate the digital cloak of our modern urban lives to highlight the inherent dignity of Earth’s multitude of other species, and the frequent fragility of these species in the face of man’s environmental footprint.

Creating collaborative projects like Lonely Loricariidae, which bridge the art-nature divide, are one of the reasons I came to ROM. I hope to join other curators here in thinking deeply about how to make visitors empathetic to the plight of Earth’s biodiversity and to use the insights gleaned from my research to spur conservation action. Collaborations with artists will be critical to that mission—as will support from readers like you.