How Iris van Herpen transformed the fashion world

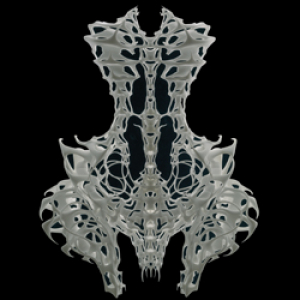

At an Iris van Herpen show, impassive models walk the runway in garments like a 3-D printed polyamide suit that more resembles a bony exoskeleton, a dress sculpted from billows of metal gauze and cow leather or a high collar made of the ribs from small umbrellas—surprising items, even in the unconventional world of haute couture. Van Herpen’s designs clothe the body, in the sense of covering the things that clothing generally covers, but it helps to think of them more as sculptures that pay homage to the bodies that occupy them.

“A lot of designers have a muse,” she says. “I don’t have one, but I think the body itself is my muse.” Van Herpen’s muse is a body with personality: a body that takes the strict poses of classical ballet, an art she has practiced throughout her life; a body that skydives, an experience that inspired one of her dresses; a body that visits sites of science and draws inspiration from them; a body that collaborates with other bodies. In other words, the body van Herpen draws inspiration from might be her own. “For me fashion is a form of art that is close related to me and my body,” van Herpen says. “I see it as a very personal expression of identity combined with desire, mood and culture.”

Her garments bring viewers inside the friction-filled world of technology and nature that she herself inhabits, both as an artist and as a human being. Van Herpen’s creations reveal what can be accomplished when you push the limits of haute couture. Her groundbreaking approach has attracted everyone from museum curators and ballet troupes to major celebrities like Bjork, Lady Gaga and Beyonce, who have all strutted their stuff in van Herpen designs.

From left: Voltage, Dress, January 2013. In collaboration with Philip Beesley Laser-cut 3-D polyester film lace and microfiber. Collection of the designer. Radiation Invasion, Dress, September 2009. Faux leather, gold foil, cotton, and tulle. Groninger Museum, 2012.0201. Magnetic Motion, Dress, September 2014. 3-D-printed transparent photopolymer and stereolithography resin. High Museum of Art, purchased with funds from the Decorative Arts Acquisition Trust and through prior acquisitions, 2015.82. Photos by Bart Oomes, No. 6 Studios.

The innovation and unconventional artistry that has put the designer and inventor in the position to have a retrospective show at the age of 33 is on full display in Iris van Herpen: Transforming Fashion. Van Herpen was one of the youngest people to join the prestigious Chambre Syndicale de la Haute Couture—as Rebecca Mead writes for The New Yorker, “the fashion world’s equivalent of a think tank”—engages with bodies, nature and technology in her work.

At her Amsterdam atelier, she unites the couture techniques of the past with materials and processes that are still being imagined, in a way that can only be described as intensely modern. Traditional couture techniques like hand-dyeing textiles and crafting plissage are combined with laser cutting, 3-D printing and liquid 3-D casting. “Traditional pattern making is also part of the process of each garment,” she told ROM magazine. “This is sometimes combined with digital file making.”

I often feel attracted to these materials that I don’t really know how to handle in the first place

“ ”Her fascination with the world around her—drawing inspiration from crows, as in her 2008 collection Chemical Crows, or from the CERN supercollider, as in her 2015 collection Magnetic Motion—is equaled by her devotion to craft and detail. Van Herpen personally handles each part of her garments with the care consistent with fine art, working collaboratively with technologists to push the boundaries of fabrication while employing traditional couture techniques in her studio. “I think I’m at the point where almost everything I 3-D print I could make by hand,” she says, “and the other way around.” Think of it as artisanal cyberpunk. “Van Herpen’s sensitive visual language is not captured in traditional flowing fabrics like silk, satin, tulle or organza,” writes visual culture critic Anneke Smelik , “but in hard materials such as leather, metal, plastic, synthetic polymers and hi-tech fabrics.”

The Dutch designer calls her style “New Couture,” and it’s as at home in a museum as on the catwalk. Doing runway shows, like those at the Chambre Syndicale where she has shown since 2011, means “you get the energy of the collection and the identity of the models,” van Herpen says, but displaying her works in a museum invites viewers to examine details and see the craft that goes into the work. There’s lots to appreciate: in one design of the three displayed from her 2009 show Mummification, ruffles of suede are paired with two types of chain, cotton and elastic to create a wide-hipped dress that presents a combination sci-fi warrior, Elizabethan courtier and 1920s flapper. So it’s no surprise that museums were some of the first collectors of her designs, although she has created wearable art for celebrities like Bjork, Lady Gaga, and Beyonce.

Before all this, though, van Herpen was her own first model. She sewed her own clothes in high school, which is also when she discovered two loves that would shape her career: working with her hands and using unconventional materials. She grew her talents at the ArtEZ Institute of the Arts, a Dutch university where she studied design, before interning with British designer Alexander McQueen and Dutch designer Claudy Jongstra. She lists McQueen as a continued inspiration.

Van Herpen’s first collection, Chemical Crows, paralleled McQueen’s ongoing interest in birds. She was inspired by crows outside her studio. But her unusual interest in materials led her farther and farther away from the haute couture mainstream. “I often feel attracted to these materials that I don’t really know how to handle in the first place,” she says. That attraction led her to work with makers from other disciplines, like Amsterdam firm Benthem Crowell Architects, her first collaborator on a dress made of polymer and modelled after splashing water, who she worked with in 2011.

From left: Chemical Crows, Dress, Collar, January 2008. Ribs of children's umbrellas and cow leather. Groninger Museum, 2012.0192.a-b. Capriole, Ensemble, July 2011. In collaboration with Isaie Bloch and Materialise. 3-D-printed polyamide Groninger Museum, 2012.0209. Biopiracy, Dress, March 2014. 3-D-printed thermoplastic polyurethane 92A-1 with silicon coating. In collaboration with Julia Koerner and Materialise. Collection of Phoenix Museum of Art, Gift of Arizona Costume Institute. Photos by Bart Oomes, No 6. Studios.

Technology is not an inspiration, van Herpen says, merely a tool. But her search for new materials has led her to the cutting edge. 3-D printing is perhaps the thing most commonly associated with her work today. These creations also landed on TIME’s list of the 50 best inventions of 2011. “Most collections start with new material developments,” she says, “but as every collection is made with different materials and techniques, the process of each collection is different and a big challenge.” “I’m in fashion, but I’m always out with one foot,” van Herpen says. In the years since, van Herpen has collaborated with numerous others, including Canadian Philip Beesley. “A true collaboration is like a precious friendship, trust and effort are really important to let it grow,” van Herpen says. “Philip is one of the most inspirational artists I know.”

A practitioner of what’s known as “responsive architecture,” the Toronto architect uses elements like light and sound that react to the viewer to create immersive spaces. Philip Beesley: Transforming Space, a new exhibit placed alongside Transforming Fashion, surrounds bodies in a novel, playful environment. Together, van Herpen and Beesley’s works represent a new frontier. As van Herpen herself says, “New terrains are found at the intersection between precision and chaos, art and science, the human touch and the high-tech, the artificial and the organic."