Learn more about what it’s like to be a wildlife photographer

Who wouldn’t want to be a wildlife photographer? You’re on a warm Caribbean beach when suddenly an endangered parrot alights near you. It fluffs its brilliantly coloured plumage and just when it looks your way you—wait a minute.

Let’s bring some reality into this picture. You’re in the Arctic. After five hours of waiting in the freezing cold, a lemming appears. It doesn’t get close enough for a good shot and soon slinks away. So do you.

In reality, wildlife photography can be rather challenging. It has been stated that the animal you’re attempting to photograph may suddenly attack you; for example, males of certain species may become more aggressive during mating season. According to wildlife photographer Paul Nicklen, however, the idea that animals are inherently dangerous is a misconception.

“I’ve been around 3,000 polar bears and never been in a scary situation, except for ones of my own making. The secret with any animal is to let them be in charge of the encounter. I start a long way away, monitor the animal’s behaviour, and let it see me, smell me, and hopefully get used to my being there. By the time I get within 20 feet of a bear it has seen me for weeks and knows I’m not a threat.”

Overambitious enthusiasts will overstep the boundaries of ethical behaviour in their quest for the perfect shot. Getting too close to an animal, startling it to make it look at your camera, and interfering with its habitat all tarnish the profession as well as stress the animal.

“It scares me when people see my work and don’t realize it has taken me weeks, sometimes months, to get that shot. They think they can race in on a Friday after work and run up to a bear: that’s dangerous for them and for the animal,” says Nicklen.

The region the photographer is working in can also harbour dangers. Wading into a leech-filled river is table stakes. At extremely low temperatures, batteries deplete quickly and condensation can damage equipment. A snake or insect bite, or a poisonous plant, can send you to the hospital—if there is one within 300 kilometres.

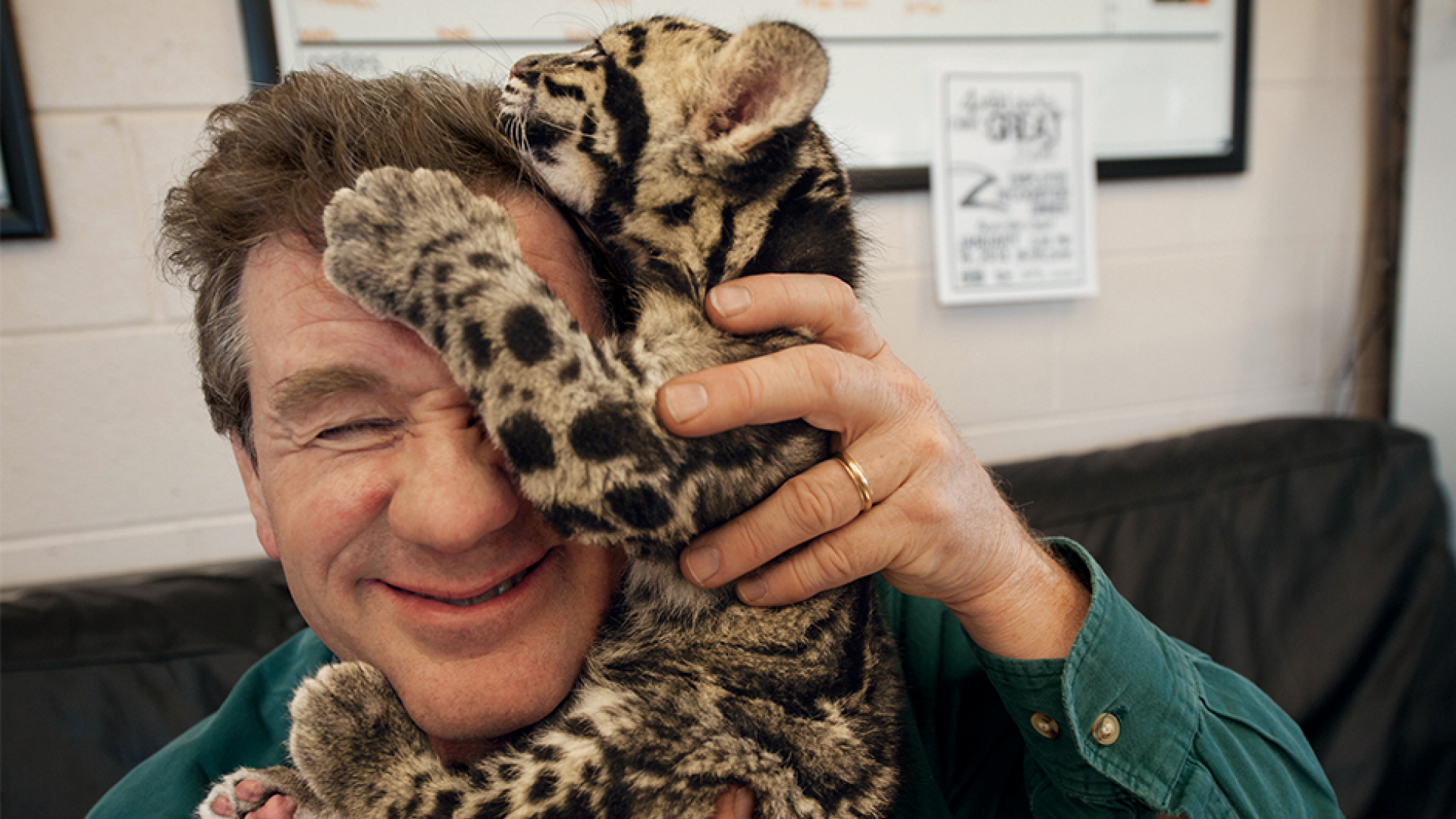

Photographer Joel Sartore recalls being bitten on the leg by a sand fly while on assignment in Bolivia: “A month later I noticed a hole on my leg that wasn’t healing. It turned out I had been infected with a microscopic flesh-eating parasite, and the only treatment was chemotherapy. It was six months before I felt normal again, and I was lucky the doctors figured it out when they did.”

So why go through all this? For Sartore, photography can expose environmental problems and help get people to care. “It’s ridiculous to think that we can destroy so many of the Earth’s plants, animals, and ecosystems and not think it can happen to us. All of this will come back to bite us.... It will not be pleasant.”

Nicklen echoes that sentiment. For him, it is an opportunity to effect change. “If you’re telling important stories through powerful and intimate photographs, people will be interested. They will share them and will want to learn more. To have that microphone is why we shoot.”