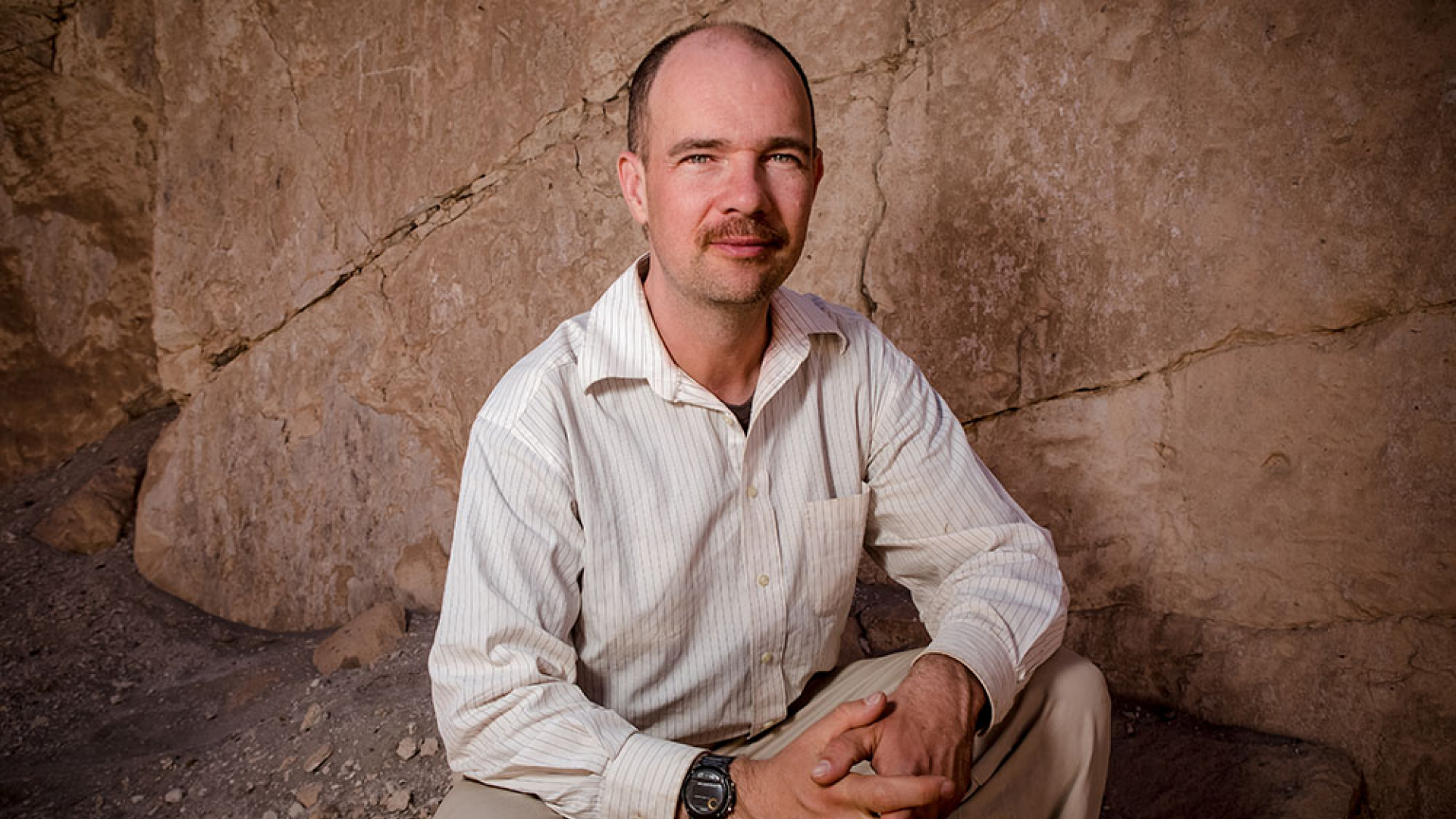

Every Thursday at 10 am on Instagram we chat with a different ROM expert ready to answer your burning questions on a different subject. This Ask ROM Anything features Justin Jennings, Senior Curator of Latin American Archaeology at the Royal Ontario Museum. He has conducted fieldwork in Peru for more than twenty years, and published on ancient states, early cities, and feasting in the Andes and other parts of the world.

Q. What’s the coolest thing you’ve come across?

A. I get that question a lot. The coolest things that archaeologists come across often come together slowly after a couple of years of excavation — we slowly put the pieces back together of what a society used to be like. In some case, that literally means putting an object back together like this face-necked jar from a site in southern Peru that we dug over two years. It likely shows an honoured ancestor and was smashed and scattered when people left the site.

Q. Could the Incas ever have caught up to Europe without contact?

A. The Incas, in some ways, were way ahead of Europe. The first Spaniards marvelled at their cities and artistry when they first came to the Andes in the 1530s. The Inca, though, had no immunity to smallpox and other European diseases and had focused much of their technological innovations on art and architecture, rather than weaponry. So in a way, the Inca were running in a different race, before the two cultures collided.

Q. How historically accurate is the Emperor’s New Groove?

A. In two words, not very. Emperor’s New Groove is an adaption of The Prince and the Pauper, a Mark Twain novel set originally in 16th century England that was shifted to the same period in the Andes by the screenwriters. For the Inca rulers, their blood was sacred — they were the sons of the sun — and they likely would have thought that a peasant was too different to even pretend to take their place. They did, though, make statues that were the embodiment of the ruler by placing the ruler’s hair and nail clippings inside of them.

Q. Favourite fun fact about Latin American Archealogy?

A. Well, I guess it’s always surprising me. A couple of years ago, for example, we learned about all of these huge, often quite old, sites on the edge of the Amazon — as more has been done, we’re really starting to re-think how the first civilizations formed throughout South America. Is that a fun fact? I don’t know, but it keeps you on your toes!

Q. How do you think the current pandemic and the limitations on travel will affect archealogy?

A. COVID-19 has hit archaeology hard. A few of my friends are fighting the virus, one on a ventilator. There are also lots of longer term impacts. Almost all summer field projects are cancelled, for example, and it’s unlikely that conferences will meet in 2021. If there’s a silver lining, then it is that time at home is perhaps giving us some time to think about all of that excavation and survey data that we’ve accumulated.

Q. What is a common misconception about Latin American society/culture?

A. I guess the common misconception is that there were three cultures Aztec, Maya, and Inca, and nothing else. The Aztec and Inca Empire were really just around in the 15th and 16th centuries CE, and the Maya are a group of people that very much remain in the region (when people say Maya they are often thinking of Classic Maya period centers that date from about 200-700 AD). There are thousands of ancient cultures in the region that did really incredible things — our job as archaeologists is to try to also tell their stories in ways that excite a general audience.

Q. What role do archaeologists have to protect sites like Machu Picchu from over tourism?

A. Archaeologists are on staff at Machu Picchu and those that visit the site will often see them in action directing the never-ending restorations that are required to maintain the site under the strain of its millions of visitors. There are also archaeologists at the Ministry of Culture — an archaeologist Luis Jaime Castillo is now the head of the ministry — and they work to find ways to best protect the site and the famous Inca roads that feed into the site. Yet even more generally, all archaeologists working the region have a responsibility to try to highlight the incredible sites that are beyond Machu Picchu to drive tourists into other regions in order to both relieve the pressure off Machu Picchu and bring tourist dollars to impoverished locales elsewhere.

Q. What’s your favourite Andean civilization?

A. My favourite civilization of the Andes? It’s the one I’ve worked on for more than twenty years — the Wari. Wari is sometimes called the first empire of the Andes and was around from about 600-1000 CE. They may have made the first quipus — the knotted strings that the Incas later used to record information — but did not have writing. So we are left to re-trace their story using pots like this one that we found in our last dig. It shows a bound prisoner with a rope around his neck. Puzzle pieces like this one help us reconstruct the Wari.

Q. What is your favourite archaeological site/museum in Peru?

A. My favourite museum at the moment is the archaeological museum of the Catholic University of Saint Mary’s in Arequipa (where I work in Peru). They’ve got a new director and he’s been digging through their collections and finding quite incredible stuff that no one has seen for years! There’s lots of museums in Peru, and often so much of it is not on display (same goes for the ROM). It’s a thrill when you find something new in these places.

Q. When did you become Interested in your field of work and what do you enjoy about being a curator?

A. Easy answer — always! Who doesn’t like digging around and finding stuff? I enjoyed playing in the sandbox as a kid, and I guess just kept going. I no longer like the sand as much (hard to keep the edges of our holes straight), but still love to be out with friends making new discoveries. By the time I went to university there was nothing else that got me as excited. As for work as a curator, some of the most exciting work is the detective work as you try to dig up what you can in the archives and library about some of the pieces that we have in our collections. We’ve got some things that have not seen the light of day in 100 years, and it is great to have a look at them!

Q. When Spain moved into Peru, were there any rural or remote parts that remained untouched?

A. The short answer is no. The diseases introduced by the Spanish wiped out somewhere between 70-90% of the native population of Peru within a century. The coast was especially hard hit, with many people moving into the highlands in a vain attempt to escape the epidemics. Labour service soon followed that sent people, often to their death, to work (often in silver mining) for the Spanish crown. Yet much of the sierra was only under nominal colonial (and later state control after independence) and continued to use kinship and reciprocity to organize much of their daily life.

Q. Is it true that we don’t actually know what the Inca referred to themselves as?

A. When the Spanish first encountered the Incas in the 1530s, they had translators who spoke their language and we have eyewitness written accounts of these encounters. The Inca did think of themselves as the Inca, but this was the name of a much smaller group of people related by blood and place (the area around Cuzco) who ruled over a much larger region.

Q. What are some traditional feasting practices?

A. What most people ate in the ancient Andes most of the time was a mix of potatoes, maize, and other grains (like quinoa). Often they had these in stews. They ate llama meat as well, the word “jerky” is derived from the Quechua word for dried meat, but in much smaller quantities. Ancient Mesoamerica was maize, beans, and chilli peppers, especially maize. As valleys got more populated, you see in particular a lot of tortilla making in some parts.

Q. Any foods that are considered special or sacred?

A. Rulers did eat differently than everyone else — what they ate and how they ate, in essence, made them a ruler. The Inca Ruler for example had a set of plates and cups that he would only touch, and servants who would make sure that anything he touched would not remain on the ground. Much of the food was made sacred by being prepared in particular ways by women devoted to serving the state.