Challenging old belief systems and offering fresh perspectives on colonial histories

Ask anyone about archaeology and they will almost certainly tell you that it has something to do with the past. Or perhaps, if you ask specifically about archaeology in North America, they’ll tell you about collecting arrowheads—some might even share a story about how they once found one themselves! While archaeology involves the study of objects from history, archaeologists find and study material traces of past human lives to say something about them in the present.

But what does it mean to think about the past in the present? How do people back then relate to the problems that we face today? What does the world’s current climate crisis, our myriad struggles for social justice, or the general anxieties we face about the future have anything to do with archaeology?

Archaeology offers us the unique opportunity to identify the assumptions that we hold dearest and to shake them until they fall apart. I refer to such assumptions as “defaults”—the “settings” that we inherit from our parents, our family and friends, our communities. I believe that archaeology has the potential to show us that other possibilities exist—there are other ways to be human; there are other ways of relating with the world around us. Archaeology can’t just be about the past. It is about the intersections of past, present, and future.

Without a doubt, archaeology offers fresh perspectives on colonial histories (a major theme of my research), but the archaeological record also provides means of challenging colonial belief systems that still persist today. For example, “terra nullius” was a designation often used to justify European colonialism. The phrase translates to “no person’s land” but was used to mean “unimproved land,” or, in other words, land that had not been modified to fit European expectations.

Colonial powers used the terra nullius designation to justify their actions, wresting lands from Indigenous peoples across the globe. And this narrative still continues to haunt us—ranging from recent struggles surrounding pipeline projects on Indigenous lands to debates about Mount Rushmore.

Almost always justified as “improving” or modifying the land from a settler-colonial perspective, these changes—including the environmental, cultural, and health risks associated with pipelines or the desecration of sacred Indigenous sites in the case of Mount Rushmore—disregard, or deny, far-deeper Indigenous histories and forms of expertise. They also tend to assume that settler-colonial transformations are the only (and best) ways of relating to the land.

Both Indigenous oral records and archaeological traces show just how skewed such interpretations and claims are. There are alternative ways of relating to the land that are distinctly not Euro-colonial nor capitalist.

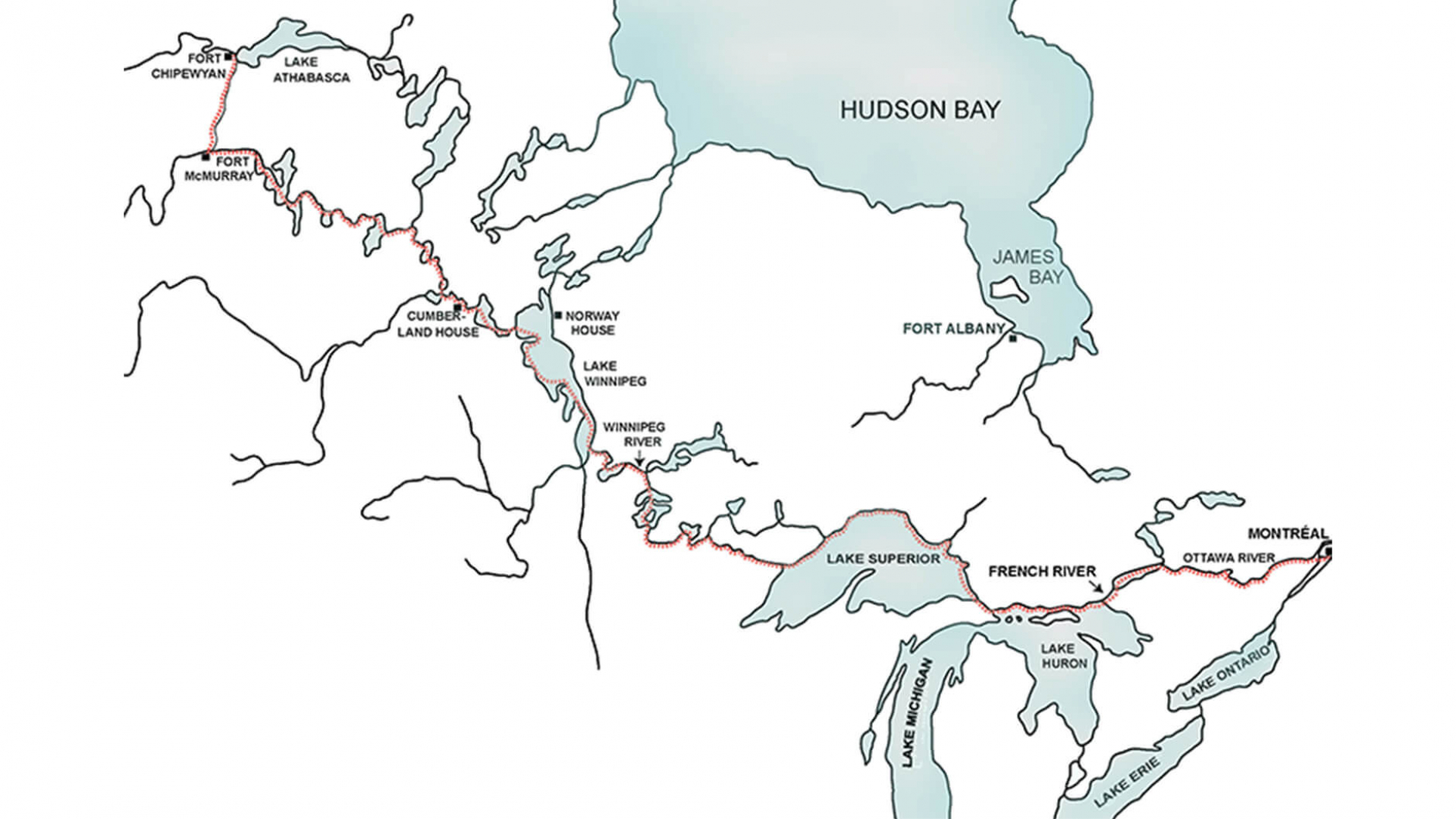

To take a local example, Ontario’s fur trade developed only through a heavy reliance upon Indigenous knowledge and understanding of the land, particularly of rivers and portage routes. ROM archaeologists and scuba divers looked into these riverways in the mid-twentieth century and found thousands of European-produced trade objects left over from the fur trade. Most of them sunk to the bottoms of rivers after canoe accidents, perhaps due to traders shooting dangerous rapids to save time. These collections are the results of disasters and finding them at the bottom of rivers shows just how wrong terra nullius was. First, the artifacts would not have been in those particular rivers without Indigenous knowledge and expertise; European colonists relied heavily on Indigineous people to find trade routes in the first place. Second, the artifacts’ presence along river bottoms stands as direct evidence of colonial failures—the rivers literally took many fur trader lives along with their trade goods because of trader misuses of the riverways.

Archaeology also speaks to our long-term relationship with things and how that association changes us, for good and bad. If you’re anything like me, you might find yourself frustrated by the fact that, without use of a smartphone, you can’t remember phone numbers or manage your way around a city. In just a decade or so, smartphones have completely changed the way most of us relate to the world around us. We focus on the obvious advantages of smartphones without thinking critically about the changes they have helped introduce.

We are far from the first people to embrace new technologies; for at least 2.5 million years, humans and our ancestors have been busy innovated new types of artifacts, ranging from stone tools to CT scanners, each meant to improve their lives in some way. Archaeology offers a valuable, long-term perspective on the impacts of technological changes like these.

Take for instance, the fur trade goods just mentioned. The archaeological record contains information on how some of these new colonial introductions to North America—including brass kettles, steel knives, and various forms of firearm—transformed how people related to their worlds.

Guns offered technological advantages for hunting, but, as with smartphones, their impacts were more than simply functional. Reliance on guns for subsistence practices eventually took the emphasis away from stone tool production, a highly specialized form of expertise. Once this skill fell out of practice, it was difficult to relearn. (If you want evidence of this, I would recommend trying to make your own arrowhead!) As those skills receded, there was an increased reliance on European traders for access to firearms or other means of feeding one’s family and community.

Changes like these factor directly into many popular understandings of colonialism and Indigenous history today. Material changes and other transformations that came about as a result of European colonialism are often framed as evidence for the disappearance of various Indigenous peoples. This forms the second side of the double-edge sword of colonialism. The first justified an annexation of lands because Indigenous peoples didn’t relate to them in European ways; the second justifies continued colonialism on the basis that Indigenous people had changed too much (by adopting European-introduced ways of life). By looking critically at these entanglements of the past, we gain new appreciations for the entanglements we are part of today.

For example, the discipline of archaeology itself is not immune to colonialism. Unfortunately, there are many parallels between the way fur traders exploited North American landscapes for profit and how archaeologist have traditionally conducted their research. That is, archaeologists were often outsiders extracting materials for personal academic benefit with little to no recognition of whose land and whose heritage they were intruding upon.

The last four decades have increasingly brought these ugly truths to the fore. How do we recognize the full diversity and breadth of the past if we only ask questions that are interesting to Euro-colonial archaeologists like me? We can’t. This is why some archaeologists have begun partnering with Indigenous communities and nations. The most impactful work in this area is conducted by projects that integrate Indigenous sensitivities, interests, needs, and expertise, with the goal of changing what archaeology will become in the future.

I currently have the privilege of co-directing an archaeological project in Connecticut with the Mohegan Tribe. Since 2010, we have trained diverse groups of students each summer, studying Mohegan-colonial histories together through the excavation of Mohegan household archaeological sites. Our collaborative methods help us understand settler colonial history in a way that is different from how we might understand it apart from one another. This is to say that through collaboration, our project is greater than the sum of its parts. Most importantly, we are also modelling a progressive and open-minded archaeology so that our students can continue to remake the discipline in ways that take into account the things they have learned while working collaboratively at Mohegan.

In the Archaeology of the Americas section of the ROM, we care for literally thousands of arrowheads along with many other types of artifact. Although traditionally prized only for the bygone times from which they originated, they are very much a part of our world today. From the deep Indigenous histories and Indigenous knowledge systems that the artifacts once participated in, to the problematic ways in which they might have been collected and housed in the intervening years—arrowheads allow us to reflect critically on how we relate to one another and to the world around us. An archaeology of the 21st century is one that is open to allowing such humble archaeological materials to challenge us in ways that reshape who we are and what we want to become.