Like many of today’s millennials, adolescent Sabre-Toothed Cats stayed with family longer than expected

Since its extinction some 11,000 years ago, the social life of the menacing sabre-toothed cat has remained a mystery to scientists and enthusiasts alike. But a new study of fossils at the ROM has uncovered the surprisingly intimate relationships between these pop-culturally beloved Ice Age predators and their adolescent offspring.

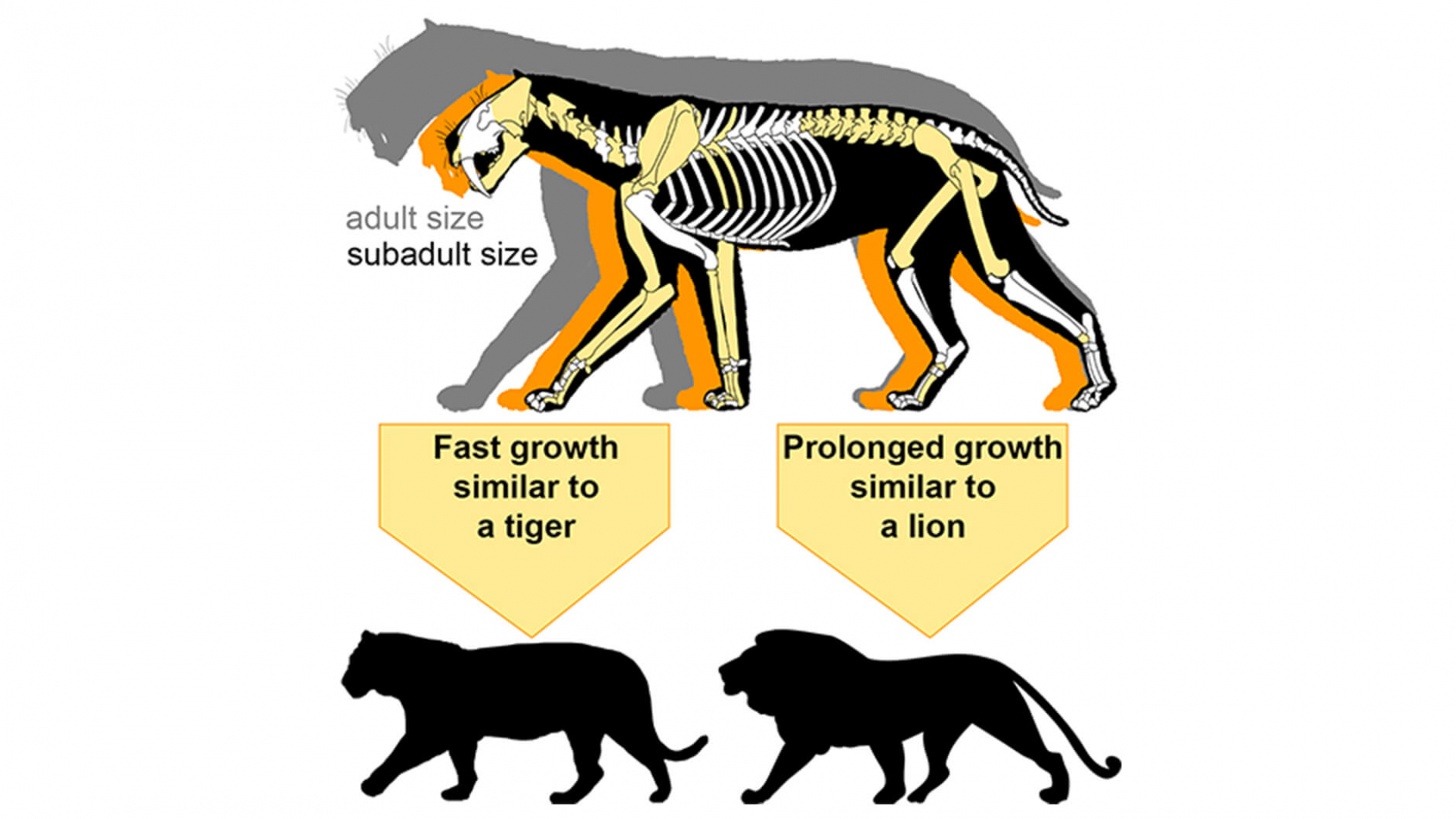

By studying a large tar deposit formed on an ancient coastal plain in present-day Ecuador, scientists at the ROM and the University of Toronto were able to document a family grouping of Smilodon fatalis. What they discovered was that while the supersized felines grew quite quickly, they also appeared to stay with their mother for longer than some other large cats before forging their own path.

The results, published in the journal iScience, provide a fascinating window into the family lives of these notorious mammals. Life, it turns out, was not too dissimilar from that of modern-day humans.

“I stopped growing taller when I was twelve, but I didn’t move away from home until many years later,” explains Ashley Reynolds, a graduate student based at the ROM who led the study while completing her PhD research in Ecology & Evolutionary Biology at the University of Toronto. “These cats seem to have been doing something similar.”

Left: A comparison of the lower left jaw bones from the two young sabre-toothed cats, S. fatalis, that were buried together. They show similar tooth formation, suggesting that the two were related. Comparison of the two left dentaries, ROMVP 5100 and ROMVP 5101. Photography by Ashley Reynolds, © Royal Ontario Museum.

Right: A sabre-toothed cat skeleton on display at the Royal Ontario Museum. Photography by Wanda Dobrowlanski, © Royal Ontario Museum.

The ROM team, which included Reynolds, her thesis advisor and Temerty Chair of Vertebrate Palaeontology Dr. David Evans, and ROM sabre-cat expert Dr. Kevin Seymour, were able to arrive at this conclusion thanks to a rare tooth condition found only in about five percent of the Smilodon fatalis population. By studying both the fossils and unique formation of the Ecuadorian deposit (obtained in the early 1960s by curators A. Gordon Edmund and Roy R. Lemon), the team discovered that three of the fossils were likely related: one adult and two “teenaged” cats. What’s more, they were able to determine that the younger predators were at least two years old at the time of their death, an age at which some living big cats, such as tigers, are already independent.

“This work is not only an important discovery in the study of these famous sabre-toothed predators, but a testament to the importance of museum collections,” says Dr. Evans. “These world-renowned collections were made by the ROM sixty years ago and have been studied for decades. But a measure of their significance is that they continue to produce new insights into the lives of these remarkable extinct animals.”