How do our stories shape our artistic expression? Walter Toshiyuki Sunahara’s visually striking paintings contemplate his childhood memories of internment in the remote interior of British Columbia during the Second World War

Walter Toshiyuki Sunahara (1935–2002) was a Japanese Canadian painter born in Vancouver, British Columbia. Considered a Nisei, a second generation Japanese Canadian, he was part of a financially successful family—his parents owned fishing boats and a guest house and were prosperous members of the Vancouver community.

In 1942, under the guise of “national security,” the Canadian government imprisoned more than 22,000 Japanese Canadians. Citizens were detained in internment camps and their businesses were seized and sold. Sunahara was seven years old when he was interned with his parents at Bay Farm, Slocan. In later years, he had a recurring nightmare where he was a small boy standing before a door that was about to be broken down.

The camp where Sunahara was imprisoned sat below a brooding conifer-covered mountain. Various aspects of his internment experience can be seen in the artist’s work throughout his life, especially his paintings.

Sunahara graduated from the Ontario College of Art and pursued graduate studies at the Tokyo University of Fine Arts (1960–63), specializing in Nihonga, a traditional expression of Japanese painting and printmaking. After trips to Southeast Asia and Europe, he came home to Canada to not only create art, but also share the means of creating art through education.

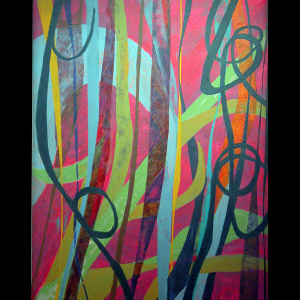

Left: Sunahara in his Toronto studio seated in front of his painting Maya Jungle. Photograph by Yoshiko Sunahara.

Right: Maya Jungle (x. 1996). Sunahara painted this work after spending a couple of weeks visiting his daughter in the Belizean neotropical rainforest at the end of one of her archaeology field seasons. From the personal collection of Kay Sunahara.

During his time at the Ontario Department of Education and the Ontario Arts Council, Sunahara was a key advocate and promoter of the visual arts community. He worked most determinedly to create opportunities and provide broader public exposure for Canadian First Nations artists and craftspeople. His work with the communities led to him being honoured with an Eagle Feather by the Ontario First Nations Cultural Centres at M'Chigeeng First Nation.

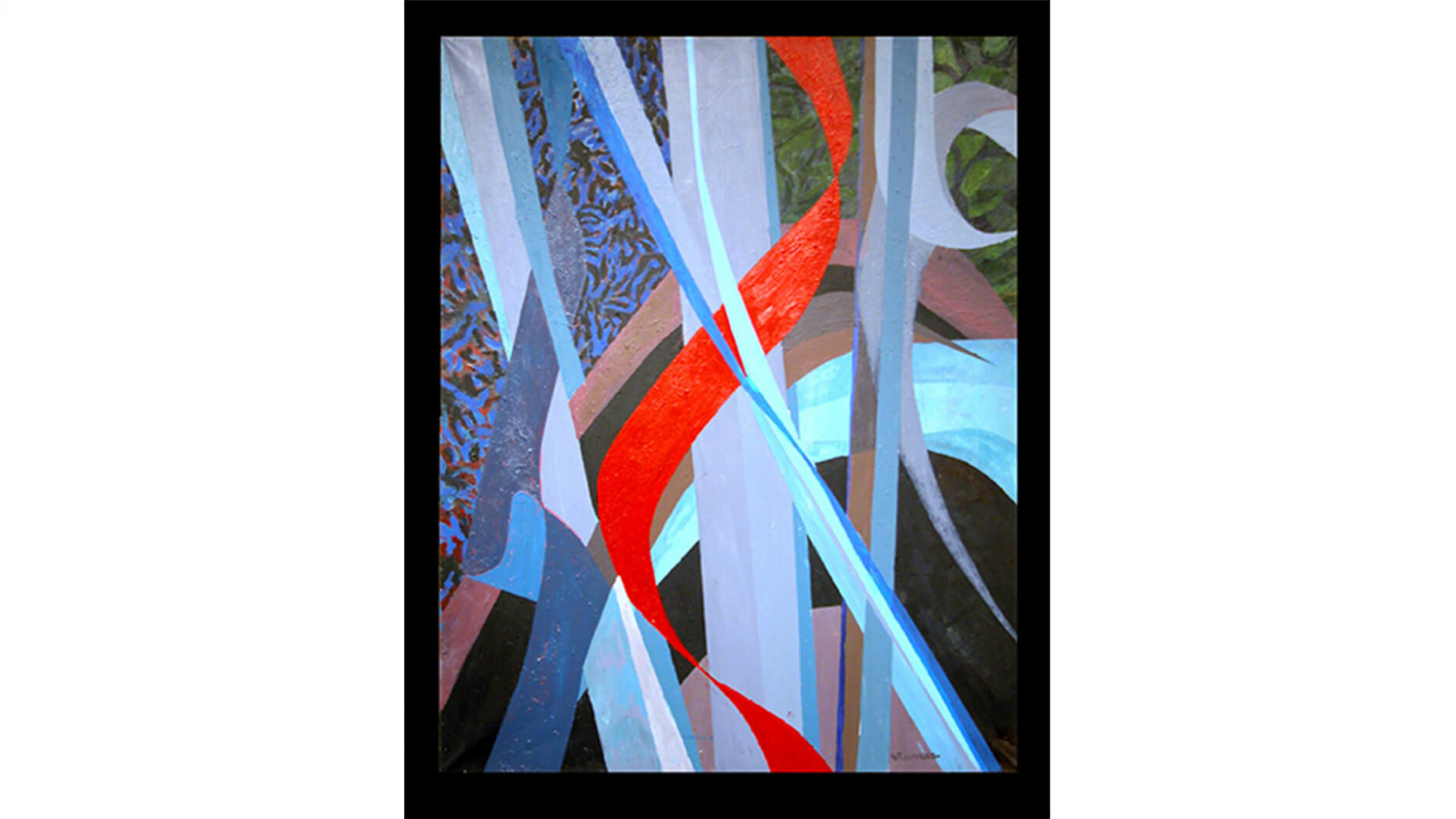

In much of Sunahara’s later work, his paintings have what appear to be ribbons running across the canvas. The curator of the "Founder Exhibit" at the Japanese Canadian Culture Centre Gallery in Toronto, Bryce Kanbara, wrote about the impact of Sunahara’s childhood experience on his artwork. “The troubled memories of parting with loved ones, which had lain dormant since childhood, pierced [Sunahara’s] artistic vision. As his wife, Yoshiko, explains, these paintings began as harmonious depictions of gardens or the natural environment, but each time, his intent succumbed to invasions of incongruous streaks and bands across the surface.”

According to Kanbara, “the interjections were driven by Sunahara’s tormented remembrance of Japanese crowds at the dock-side—the departees on board and the well-wishers below attempting to maintain links with one another for as long as they could by grasping the ends of paper tape cascading from the ship. They are abstract paintings that sublimate themes of historic and personal separation, anxiety and loss.”