The little bear that charmed readers around the world

In 1926, A.A. Milne and E.H. Shepard introduced Winnie-the-Pooh to the world. Yet the bear’s journey into print was a long and circuitous one that crossed an ocean and took a dozen years.

Winnie-the-Pooh’s story begins in White River, Ontario—a railroad town deep in the forest. On August 24, 1914, its small population swelled with soldiers for a few hours during a Canadian Pacific train stopover. Great Britain had entered the First World War earlier that month, and many Canadians answered the call to volunteer. Among the first was Harry Colebourn, a 27-year-old veterinarian from Winnipeg who was travelling with other members of the Canadian Expeditionary Force for six weeks of training at Camp Valcartier in Quebec. Their train stopped to resupply in White River, and Colebourn disembarked with the other men to explore the town.

Most of what we know about his stopover comes from the few words scrawled in his day planner: “Left Pt. Arthur 7A.M. Train all day, Bought Bear $20.” Buying a bear during a layover might sound odd, especially when one realizes this is around $500 in today’s money. Yet regimental mascots were seen as good for morale, so when Colebourn saw a trapper selling a black bear cub, he may have felt it was his patriotic duty to buy it. He named it “Winnie” after Winnipeg.

A playful cub with a sweet tooth, Winnie was a favourite with the troops in Valcartier. In October, she and Colebourn crossed the Atlantic in a ship convoy bound for more training on England’s Salisbury Plain. When Colebourn was about to depart in early December for combat in France, he loaned Winnie to the London Zoo. She swiftly became a crowd favourite and continued to delight a generation of children after she was officially donated to the zoo at war’s end. One of these young admirers was Christopher Robin Milne.

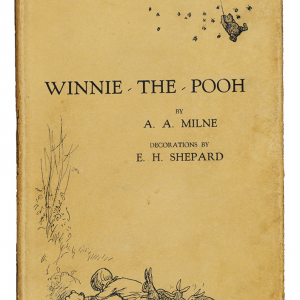

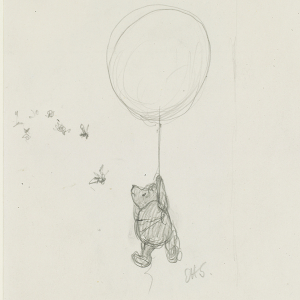

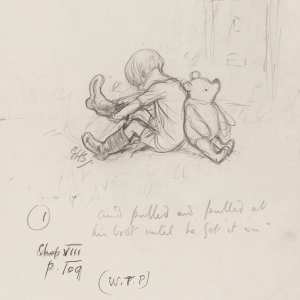

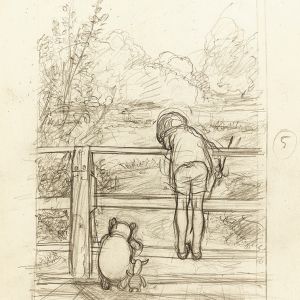

(1) Winnie-the-Pooh, UK first edition. (2) “Bump bump bump” (first sketch). From Winnie-the-Pooh, chapter 1, frontispiece, 1926. E.H. Shepard, pencil on paper. (3) “The bees are getting suspicious.” From Winnie-the-Pooh, chapter 1, 1926. E.H. Shepard, pencil on paper. (4) “And pulled and pulled at his boot … The first person he met was Rabbit.” From Winnie-the-Pooh, chapter 8, 1926. E.H. Shepard, pencil on paper. (5) “For a long time they looked at the river beneath them.” From The House at Pooh Corner, chapter 6, 1928. E.H. Shepard, pencil on paper.

Born in 1920, Christopher Robin was the only child of Alan Alexander Milne and his wife, Daphne. He loved visiting Winnie at the zoo, as evidenced by an iconic picture of him feeding her sweets there. Other photographs taken around this time show him cradling a bear stuffie his parents bought him for his first birthday. More animal stuffies soon followed, and the boy played with these toys in his London nursery, imbuing them with character traits—Tigger’s bounce, Eeyore’s glumness—that would carry over into the Winnie-the-Pooh books (see below).

Christopher Robin’s bear made his first appearance as “Mr. Edward Bear” in When We Were Very Young, Milne’s collection of children’s poems published in 1924. It was a commercial success, in no small part because of Shepard’s wonderful illustrations. He drew Edward Bear to look like his own son’s teddy bear, and this style would continue in subsequent books by Milne and Shepard, including The House at Pooh Corner (1928). Meanwhile, Christopher Robin had decided to rename his stuffie “Winnie-the-Pooh”—“Winnie” in reference to the bear at the zoo and “Pooh” after the name of a swan he fed in the park. In 1925, the Milnes bought a country home 90 kilometres south of London. Christopher Robin would take Pooh and the other animals on adventures in the neighbouring woods. These adventures, infused with his father’s own childhood memories, inspired the Winnie-the-Pooh books. Meanwhile, Winnie was still at the London Zoo, thrilling children who got to see a bear that had played a small but crucial role in the creation of books that would sell millions of copies the world over.

Christopher Robin would take Pooh and the other animals on adventures in the neighbouring woods. These adventures, infused with his father’s own childhood memories, inspired the Winnie-the-Pooh books.

“ ”Winnie-the-Pooh: Exploring a Classic in part, tells the story of Winnie-the-Pooh’s origins. Created by the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, the exhibition of more than 200 objects uses family photos, stuffed animals, line drawings, sound recordings, video clips, and other media to usher people into the homes of Milne and Shepard in the years prior to Winnie-the-Pooh’s publication. The ROM’s new addition explores the Canadian connection, featuring Colebourn’s original 1914 diary and taking us from the forests of Ontario to the London Zoo.

The exhibition also delves into the whimsical world of the Hundred Acre Wood, where we find out how Shepard’s original drawings paired with the text to impart important lessons about friendship and teamwork. Most importantly—at least for the kids among us—we can ring the bell as we go into Pooh’s house, take a turn on the slide, and play Poohsticks on the bridge with our friends. We also see the books go out to print and marvel at Pooh’s wide and enduring legacy.

For those who grew up with Winnie-the-Pooh or read the books to their children, the exhibition evokes a flood of happy memories. There’s Pooh hanging from a blue balloon, Piglet and Christopher Robin looking down on a Heffalump, and Eeyore checking for his tail. The ROM is the final stop for Winnie-the-Pooh: Exploring a Classic, and a fitting place to end its run. The story of Winnie-the-Pooh began in Ontario, and we are delighted to have Pooh visit us again.