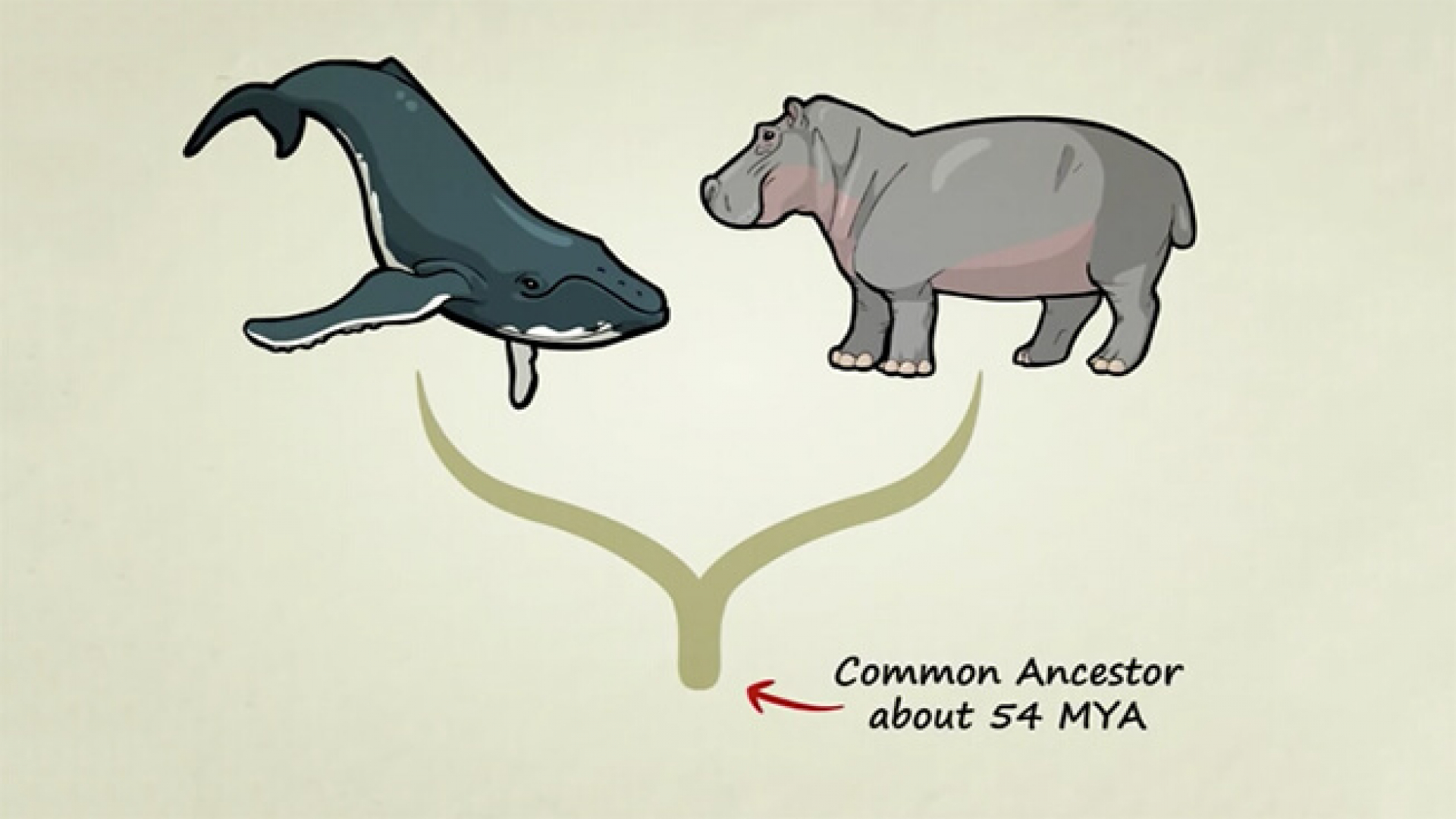

Hippopotamus and whales are much more closely related than you might guess

Looking at whales, you might have a hard time figuring out where they fit into the mammalian family tree. In fact, hippopotamus are actually whales’ closest “cousins”, and they're much more closely related than you might guess. Based on their fossil record, scientists have determined that whales are related to land dwelling mammals that lived on Earth between 52–47 million years ago. These early whales were well adapted to coastal habitats, and over time were slowly able to transition to the fully marine whales we recognize today.

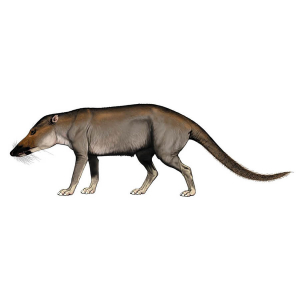

The “first whale” that we know of doesn’t really look anything like a whale at all. This first ancient whale’s name is Pakicetus. Pakicetus lived entirely on land but was well adapted to swimming much like dogs or bears. Interestingly, in 1859 Charles Darwin related a scene of a swimming bear catching insects in the water to that of a whale catching its food and even alluded to the possibility of a bear-like creature being rendered by natural selection to become increasingly marine, eventually giving rise to something such as a whale.

The process of natural selection works over time to better adapt animal’s traits to their environments by having higher survival rates amongst the animals that have the more adaptive trait. Natural selection however can’t act on a trait which doesn’t already exist. A much smaller scale example of natural selection can be seen in the colouration of deer mice in the Sandhills of Nebraska. These mice have developed two very distinct colours based on which environment they are living in within the same general area. Depending on the colour of the soil where they live, they have adapted a colour in which they are the most camouflaged from predators. The mice with dark coats has a better chance of survival on the dark soil, and the mice with the light-coloured coats had a better chance of survival on the light soil, thus becoming two distinct populations. Within just 8,000 years this change has already altered their DNA by a single gene. The differences in these populations could grow to be even more distinct.

Like with the deer mice of Nebraska, natural selection slowly shaped the ancient ancestors of whales to become increasingly adapted to their habitat. While Pakicetus was bear-like, Ambulocetus, with big feet, thicker thighs, and a tail more suitable for swimming, looked much like a furry alligator. This creature was still living on land but was also quite comfortable in the water and lived between 48–41 million years ago.

Kutchicetus, another ancient whale relative, was entirely marine. Kutchicetus had a flat tail that it would have used to swim by moving up and down. Most strikingly, this animal’s snout was elongated with its nostrils on top to allow its body to be mostly submerged while still able to breathe. Similarly, the creature’s eyes were also located near the top of its head in order to see its prey near the shore, while its body was underwater, these adaptations are seen in a wide variety of aquatic and marine animals today.

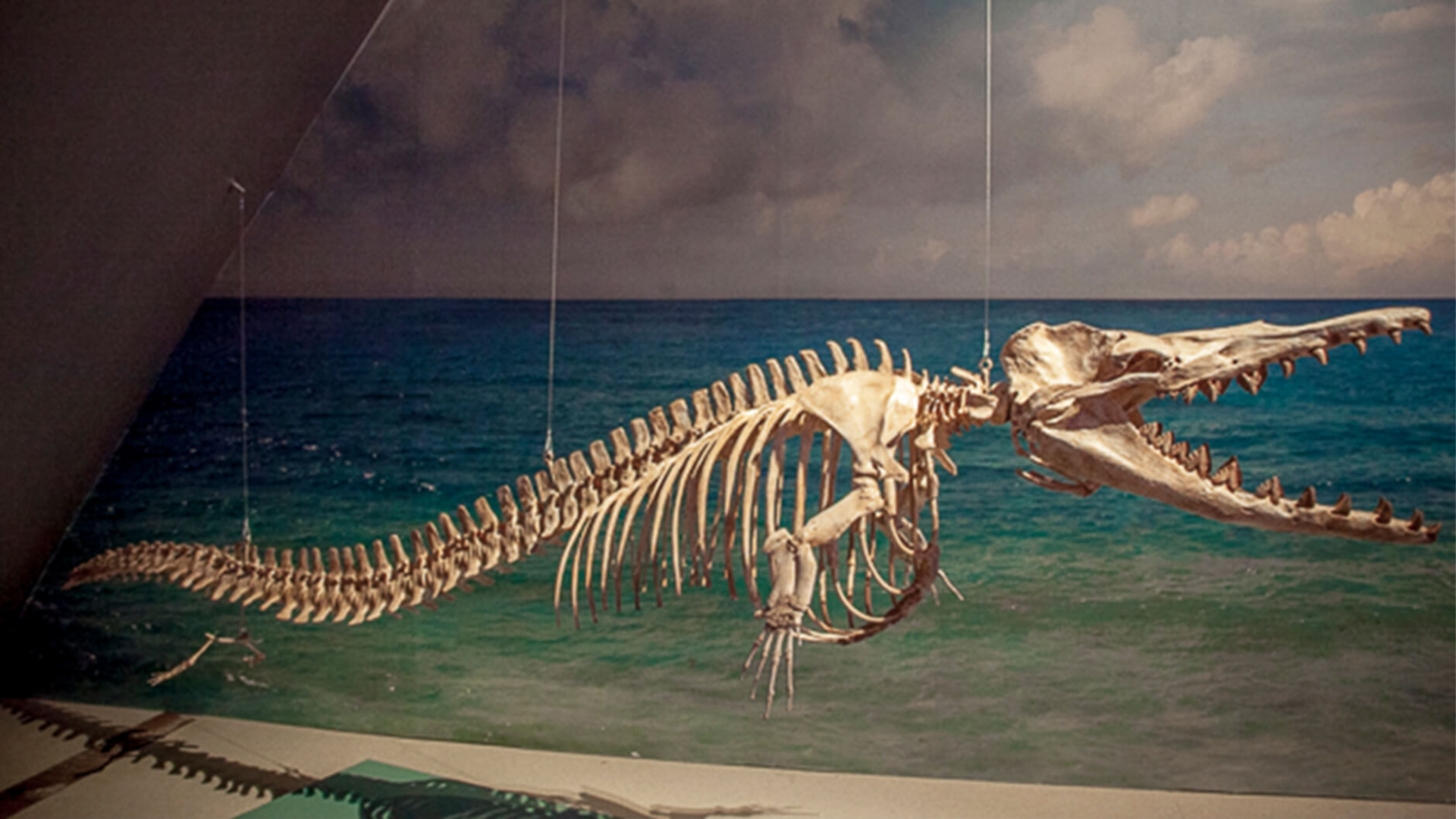

Maiacetus and Dorudon are two final examples that show us ancient whales fully adapted to marine life. With hind limbs separated from their spinal column, they were unable to support weight on land. Maiacetus and Dorudon had ear bones much better adapted to hearing underwater as well as teeth and jaws more adapted to gripping and slicing their prey.

But what do all of these ancient creatures have in common with modern whales and hippos?

Scientists in the late 1700’s first noticed similarities between whales and hippos through their reproductive organs but thought they were incidental. It wasn’t until the 1980’s when the skeleton of Pakicetus was first discovered, containing remnants of bones found only in whales (Cetacea), and even-toed hoofed mammals (Artiodactyla), such as camels, pigs and giraffes.

The ear bone in Pakicetus contains two unique features that are found in Cetacea and Artiodactyla, the involucrum and a sigmoid process—responsible for allowing whales to hear underwater. Pakicetus’ skeleton also contained a uniquely shaped ankle bone, containing a double-pulley feature only seen elsewhere in even-toed hoofed mammals but not found in odd-toed hoofed mammals such as horses or rhinoceros.

More recently, modern science allowed for even further developments in this fantastic detective story. A DNA research study into the relationship between whales and even-toed hoofed mammals revealed that whales do in fact share similar gene sequences with the Artiodactyla. Furthermore, the DNA testing revealed that whales share a DNA sequence found only in one other animal—indicating that among all the non-whale mammals alive today, whales’ closest living relatives are none other than hippopotamus!

The transformation of animals like Pakicetus into animals like Dorudon is a truly phenomenal tale, as the process of natural selection took a mere 10 million years. Though that may seem like a very long time from a human perspective, it is virtually a blink of the eye in the history of our planet. For an animal that looks like a bear or wolf to give rise to something as dramatically different as a whale, in such a comparatively short period of time, is one of the most remarkable transformations witnessed in the fossil record. Natural selection was working in overdrive when it comes to whales!

The extraordinary 50-million-year old connection between hippos and whales confirms the importance of understanding their shared heritage, and informs our understanding of the lives and environments of modern whales. The ancestry of whales as mammals, as hoofed mammals, can only inform our conservation efforts after the destructive relationship humans have had with them over the last two centuries. Knowing their past can only help us further understand and contextualize how whales make their existence today, and how we can better conserve them for the future.

Explore More

In 2017, we shared the incredible journey of Blue, ROM’s beloved blue whale, in Out of the Depths: The Blue Whale Story. Fast forward four years and we’re going back to the depths.

Opens June 26, 2021

American Museum of Natural History

The Harvard Gazette

Stated Clearly