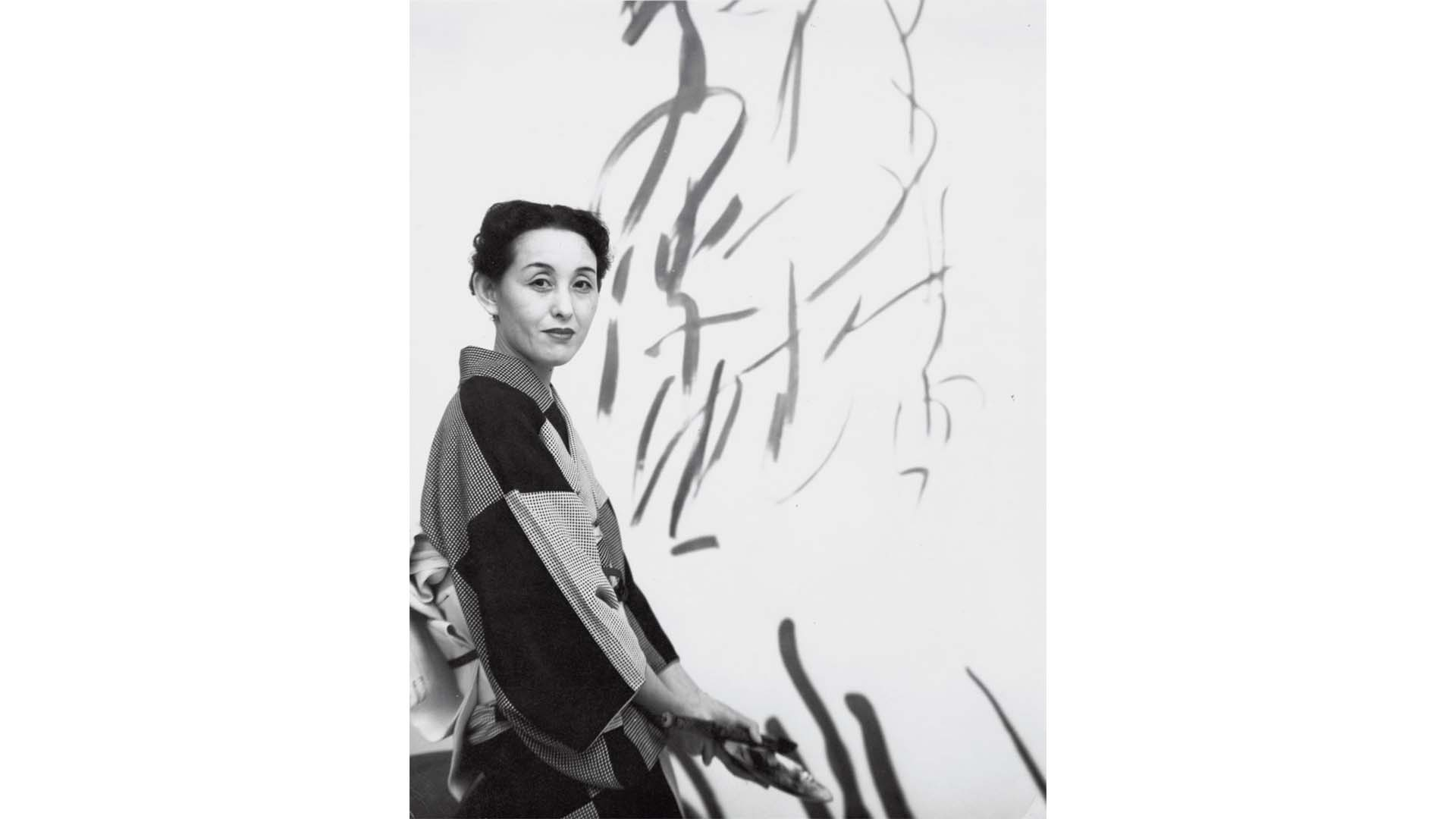

An artist whose individuality could not to be confined to specific genres of art

The extensive and versatile career of Tōkō Shinoda, who passed away in 2021 at the age of 107, makes us reflect on how artistic achievements are recognized through the life of the artist. As an artist who experienced a major break in her career in the mid-1950s, the longevity of Shinoda’s work is a testament not only to her creativity but also to her individuality that could not to be confined to specific genres of art.

Shinoda started her career as a calligrapher and became known for her abstract visual compositions using sumi ink from the 1950s and continued producing such works over the course of six decades. Borrowing Shinoda’s own words, her art captures vague, evanescent images of transient things, such as breeze, air in motion, or forms of mind. In Toko Shinoda: A New Appreciation, published in 1993, gallerist Marjorie Chu describes Shinoda’s works as a natural and effortless combination of two seemingly opposite elements—solidity of bold black of sumi ink and translucence expressed by subtle shifts of textures.

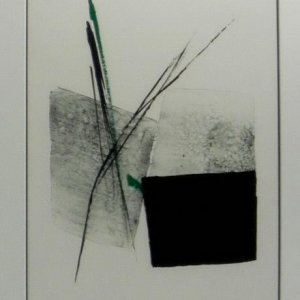

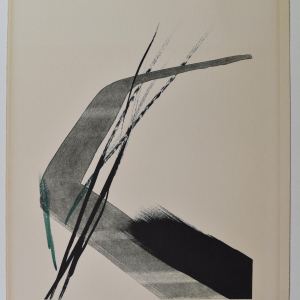

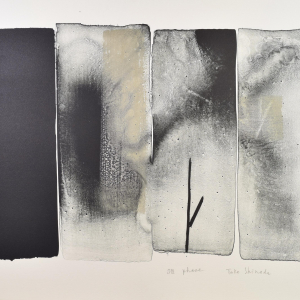

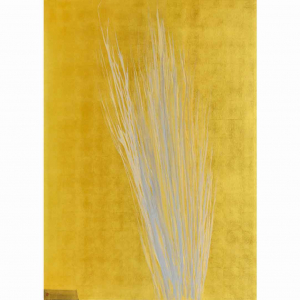

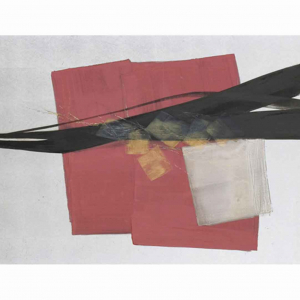

Three lithographs by Shinoda Toko in ROM's collections: (from left) Winter Green (1990), Sprout (late 20th century), and Phase (late 20th century).

While her abstract works are often categorized as painting today, Shinoda did not identify herself as either a calligrapher or a painter. She maintained a fine balance between calligraphy and painting, “a rare artist whose modernism is rooted in tradition without compromise in either direction,” as described by the art critic John Canaday in the New York Times in 1972. Shinoda and her works refuse definitive categorization, and as Chu observes, the artist transcended “the boundaries of geography; the limiting definitions of what is Eastern and what is Western; the sense of time, of past versus present; and the restrictions of social expectations and cultural philosophies.”

Floating Weed: Career Beginnings

Shinoda was a self-trained calligrapher who started her career in pre-war Japan. At the age of 27, she had already determined her artistic direction toward abstract calligraphy—a style where the visual forms of letters surpass their meanings, and one that is considered avant-garde even today. Given the highly conservative society of Japan in the 1940s, such a decision to pursue an unconventional style must have required strong determination, courage, and self-confidence for a young woman. And her endeavour was not without its share of setbacks. Her first solo show of abstract calligraphy in 1940 was negatively reviewed as “floating weed” (ne-nashi gusa), an expression of describing an insecure, unsubstantial way of life.

Modernizing Calligraphy in Japan

Within the Japanese calligraphy world, the struggle for breaking with tradition was felt as early as the 1930s, but it was after the end of World War II in 1945 that calligraphers began seriously modernizing this form as an independent category of “fine art,” partly because of the Allied Occupation Office’s Japanese language reform, under which the traditional writing system had a potential to be eliminated.

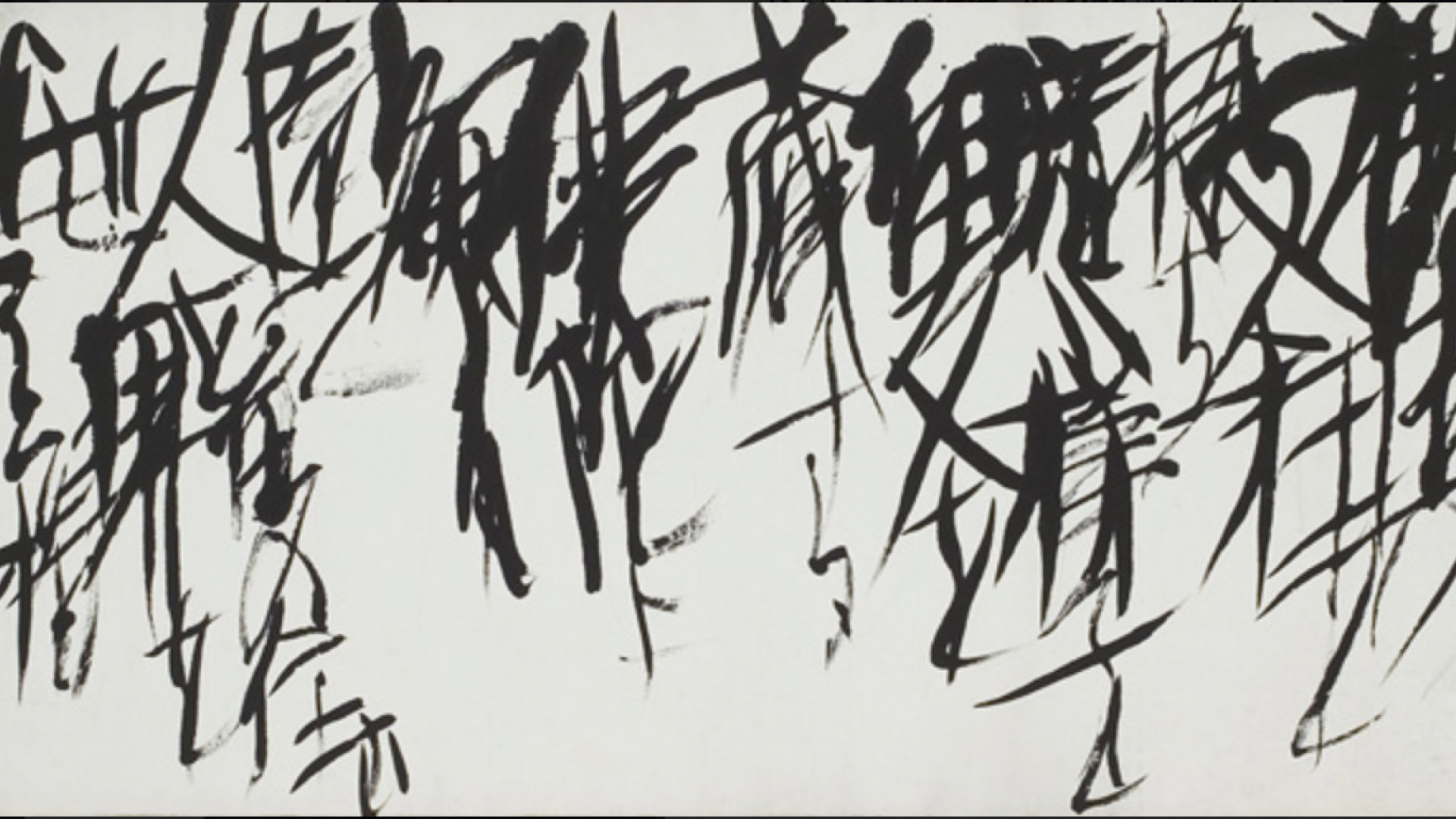

Some calligraphers tried to modernize it within the framework of traditional calligraphy where the meaning of the written letters occupied the primary importance. Others went beyond the traditional restrictions to focus more on the visual treatment of letters than their meanings, and to depict them as a reflection of the artist’s state of mind.

Among the latter, emerged artists devoted to avant-garde calligraphy around 1946. It is not certain how much Shinoda received inspiration from these movements, as she did not belong to any groups of artists, but she must have been aware of them when she decided to take a similar direction toward abstraction.

One of such avant-garde groups of calligraphers, Bokujin-kai, began actively seeking international exchanges with foreign abstract painters, as it was the time when new forms of abstract painting started emerging both in the US (Abstract Expressionism) and in Europe (Art Informel). Both sides of the exchange mutually found synchronicity in their works, although the interactions were short-lived. The dilemma of Japanese avant-garde calligraphers was—and still is—that the more they want to go beyond the tradition of calligraphy, the more their works are considered “paintings,” despite their pride as calligraphers.

While “painting” and “calligraphy” in Japan were historically considered equal and sharing the same root, following the ancient Chinese idea, the boundary between “painting” and “calligraphy” has been controversial since the late 19th century, when calligraphy was eliminated from the new category of “fine art,” where painting became the primary medium. The works of avant-garde calligraphers and their interactions with foreign artists have not officially been recognized within the narrative of Japanese art history, precisely because they were not “art.” Because of this dilemma, many avant-garde calligraphers active in the 1950s–60s eventually turned their direction back to more conventional calligraphic style.

Left: Hyaku (Hundred). Courtesy of Nabeya Bi-tech Kaisha. © Shinoda Sōko. Right: Shadow of Wind. Courtesy of Gifu Collection of Modern Arts Foundation. © Shinoda Sōko.

An Independent International Artist

Within such a complex world of modern calligraphy, Shinoda occupied a peculiar position. It seems she remained highly independent and followed through her own way. While she was often referred as a painter, she never identified herself as such, which left her works free to be interpreted as calligraphy, according to scholar Takayuki Kurimoto.

Shinoda has been internationally acclaimed since the early stage of her career in the mid-1950s. As early as 1954, her work was included in the Japanese Calligraphy exhibition at MoMA in New York, an exhibition that introduced Japanese avant-garde calligraphy. She then moved to the US in 1956 (one year earlier than Yayoi Kusama), and her works were received as part of the Abstract Expressionism and Art Informel movements that were a huge artistic phenomenon at that time.

Shinoda’s dignity as an independent artist can be seen when she talked about her experience in abroad in 1956-1958. In New York and Paris, she encountered artists such as Mark Rothko, Jackson Pollock, Robert Motherwell, and Pierre Soulage. It is often the norm in modern art history that non-Western artists’ encounter with Western artists is almost always interpreted as the latter’s influence on the former. Even a few Abstract Expressionist artists, who proved to have received inspirations from Japanese avant-garde calligraphy, were reluctant to admit the fact in public at the time. Shinoda, on the other hand, described her experience as “sharing” ideas and opinions with those artists and refused any one-way influence from Western art in the interview with United Press International in 1980. She insisted that she belonged to no movement and her work was Japanese in nature in every respect in a Business Times interview in 1998.

While successful in abroad, the reason why she returned to Japan after two years in 1958 was climate: Shinoda realized that the drier air in the US made her sumi ink dry up too fast and it did not soak into the paper as she wished. This attests how sumi ink remained the most significant part of her works throughout her career.

She extended the media to lithograph print, mural painting, book design, as well as essay writing from the 1960s on. ROM's three lithographs are reminiscent of her abstract calligraphy that was developed into simple plane of monochrome. While there is no trace of letters, we can find calligraphic expressions in the interplays of various tones of ink, expressed with different sizes of brushes from very thin to thick. Because the starting point of Shinoda’s works is calligraphy, the resulting abstract compositions always embody the nature of re-configuration and immediacy of time that are not necessarily found in paintings, as Japanese art critic Ichiro Haryu commented in 2005.

Shinoda continued to be acclaimed world-wide. Pierre Alechinsky, Belgian artist of the Informel movement, who was greatly inspired by Japanese calligraphy, created a film Calligraphie Japonaise in 1956, featuring Shinoda and three other artists, which indicates her influential position as part of the renowned “Japanese calligraphers” at that time. Newsweek Japan selected her as one of “100 Japanese” in 2005, and more recently in 2011, gallerist Richard Ingleby called her “one of the greatest of all 20th-century Japanese artists.”

Obscure Fame in Japan

In Japan, however, Shinoda was known more for her longevity, independent personality, and the spirit of dignity, mainly through her multiple best-selling publications. These acclaimed characteristics overshadowed her distinctive artistic achievements: as one of the pioneering abstract calligraphers in the 1950s, as one of a few female artists who ventured to live in abroad when traveling to foreign countries itself was still not easy for most Japanese, or as an artist who freely crossed the boundaries of artistic category, from calligraphy to painting, from prints to essay writing. When Shinoda passed away this year, journalist Emily Langer wrote in her that “[i]n some critical estimations, [Shinoda] was denied the degree of fame her talents deserved.”

Only for a short period were Shinoda’s achievement as an artist widely celebrated in Japan. This was right after she returned from the US in 1958, because it was simply sensational that a female artist would return to Japan after making her name among leading American artists of the time.

When such temporary attention waned, however, Shinoda’s name disappeared from the narrative of Japanese art history. Some possible reasons could be that Shinoda was a female artist—the Japanese art world has traditionally been male-dominated, especially prior to the 1990s; or because Shinoda did not belong to any artistic groups nor participated in open-call exhibitions—the narrative of modern art history has focused on tracing the collective movements as art groups played the central role in Japan since the late-19th century to the post-war era. Or perhaps it was because of Shinoda’s implicit refusal to have her works defined either as calligraphy or painting—art critics and scholars tended to stick to their own specializations, and only a few were able to examine Shinoda’s accomplishment

But another reason for Shinoda’s disappearance from Japanese aet history could possibly be due to the strong presence of private collectors, and a commercial gallery representing her works. It is possible that her success in commissioned works, print sales, or even bestselling publications, might have been seen as commercial activities, creating an impression of Shinoda as a “market-driven” artist.

The fact is that her works have constantly been exhibited and collected both in and out of Japan for over six decades, which itself is an unparalleled accomplishment. The long, independent career of Shinoda requires a close and extensive examination. It is hoped that Shinoda’s art would be celebrated and situated in perspective with the broader visual expressions that surpass artistic and geographical boundaries.