A glimpse into the lives of Canadian missionaries in the early 20th century

Travel restrictions brought on by COVID-19 have made us all appreciate, more than ever, the close connections we maintain with our families and friends through modern communication technology, be it video calls, phone calls, emails, or instant messages. But a century ago, the news retold in written letters from loved ones who lived far away were hardly current. Imagine the reaction of a mother, whose son is a new doctor with the Canadian missionary, discovering through a letter that he survived a boat wreck in China. This story is one of several communications uncovered through the ROM’s recent donation of personal letters, photographs, evangelistic documents, religious posters, and ephemeral objects, from Canadian missionaries who lived and worked in China during the first half of the 20th century.

The ROM has several renowned Chinese collections brought to Canada by early Canadian missionaries (such as, the George Leslie Mackay collection, Bishop William Charles White collection, and James Mellon Menzies collection). Many of these collections focus largely on Chinese artifacts about Chinese culture and society. Recent donations by the descendants of Canadian missionary families, however, reveal a different view of China—one that looks at life through a uniquely Canadian lens/perspective. The materials, donated by three families—Dr. Walter T. Clark (1874–1955), Albert E. Grant (1907–1982), and John Alfred Austin (1910–1991)—chronicle the journeys of these Canadian missionaries who sailed out from Toronto to China during the early 20th century under the China Inland Mission (CIM). The Mission, now known as Overseas Missionary Fellowship, was funded by a protestant Christian missionary James Hudson Taylor (1832–1905) in 1865. All three men arrived in China while in their early 20s. And each of them, at different point in their lives, was joined by Western missionary women whom they married and started a family with.

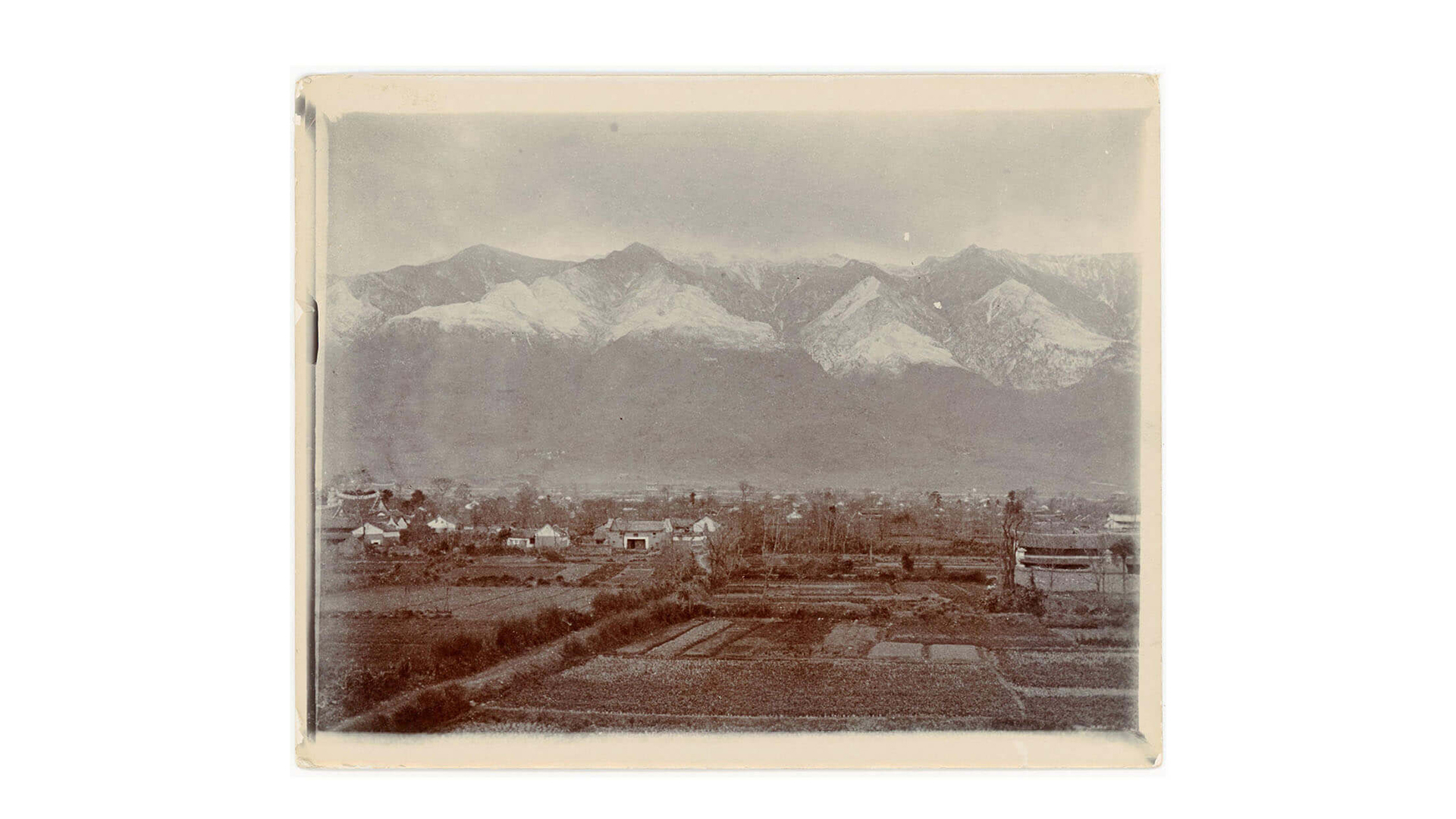

In this article, we look at Dr. Walter Clark’s experience in China. The maternal grandfather of ROM donor Patricia Kennedy, Clark underwent intensive language training and passed difficult exams (including preaching a sermon in Chinese) after arriving at China in 1901. With a medical degree from University of Western Ontario, Dr. Clark was eventually posted in an Anglican sector of China in “Tali fu” known as Dali today, in the Yunnan province, where they needed a doctor.

CIM’s missionary work had reached Yunnan two decades before Dr. Clark’s arrival. In addition to spreading the Christian message, the earlier missionary work was mainly devoted to treating opium addiction. Ironically, it was the two Opium Wars, between China and the West, during the 19th century that allowed opium to be a regular item of trade and penetrated all levels of Chinese society. It would be these “unequal treaties” as a result of the Qing empire’s military defeats that allowed Western missionaries into China. CIM was the first to establish their missions in inland China.

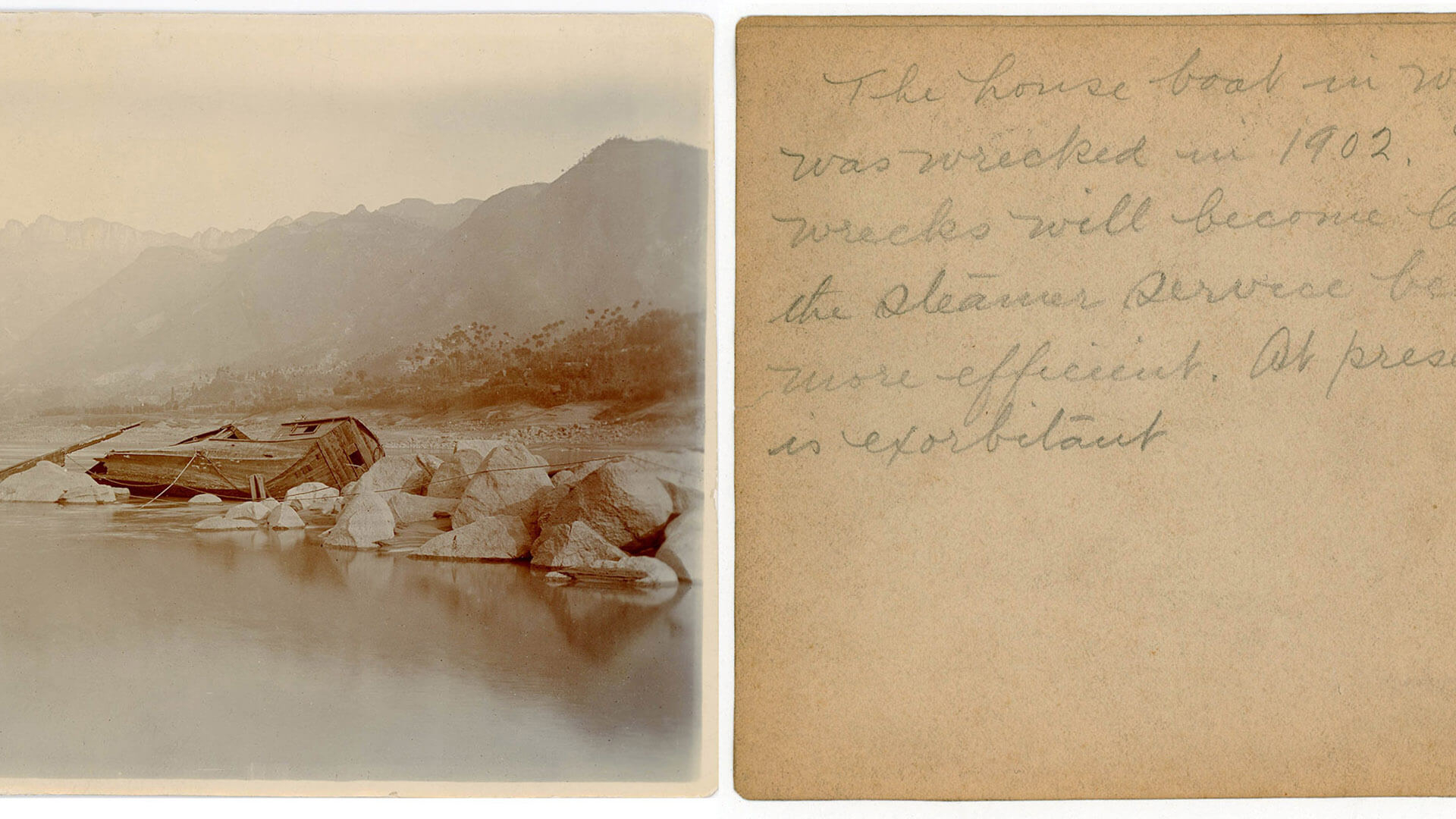

Dr. Clark wrote regularly to his mother, nearly every other week. The surviving letters are mostly from 1907 and 1908. These letters give us the most vivid, first person account of his life and work. What the Clark family now calls the “China Wreck Letter” tells the dramatic events of how Dr. Clark’s boat crashed on a rock during his journey to the West with other missionaries.

When the boat got stuck in the river, they tried to rescue as many of their personal possession, along with more than 100 cases of supplies for other missions, which unfortunately were all damaged. Despite losing his photograph album and many photos, Dr. Clark was relieved that his camera sitting on the tripod was out of reach of water!

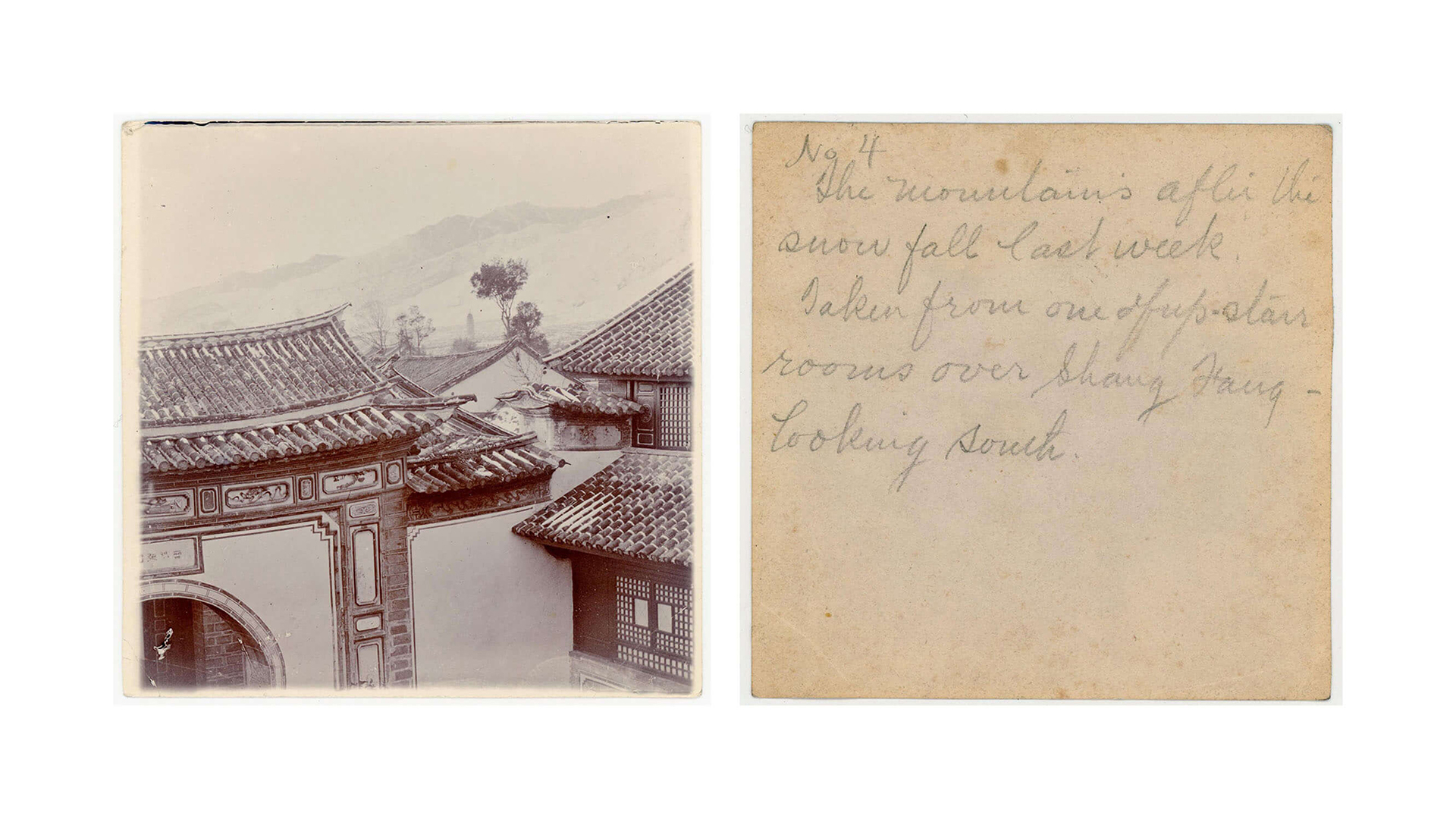

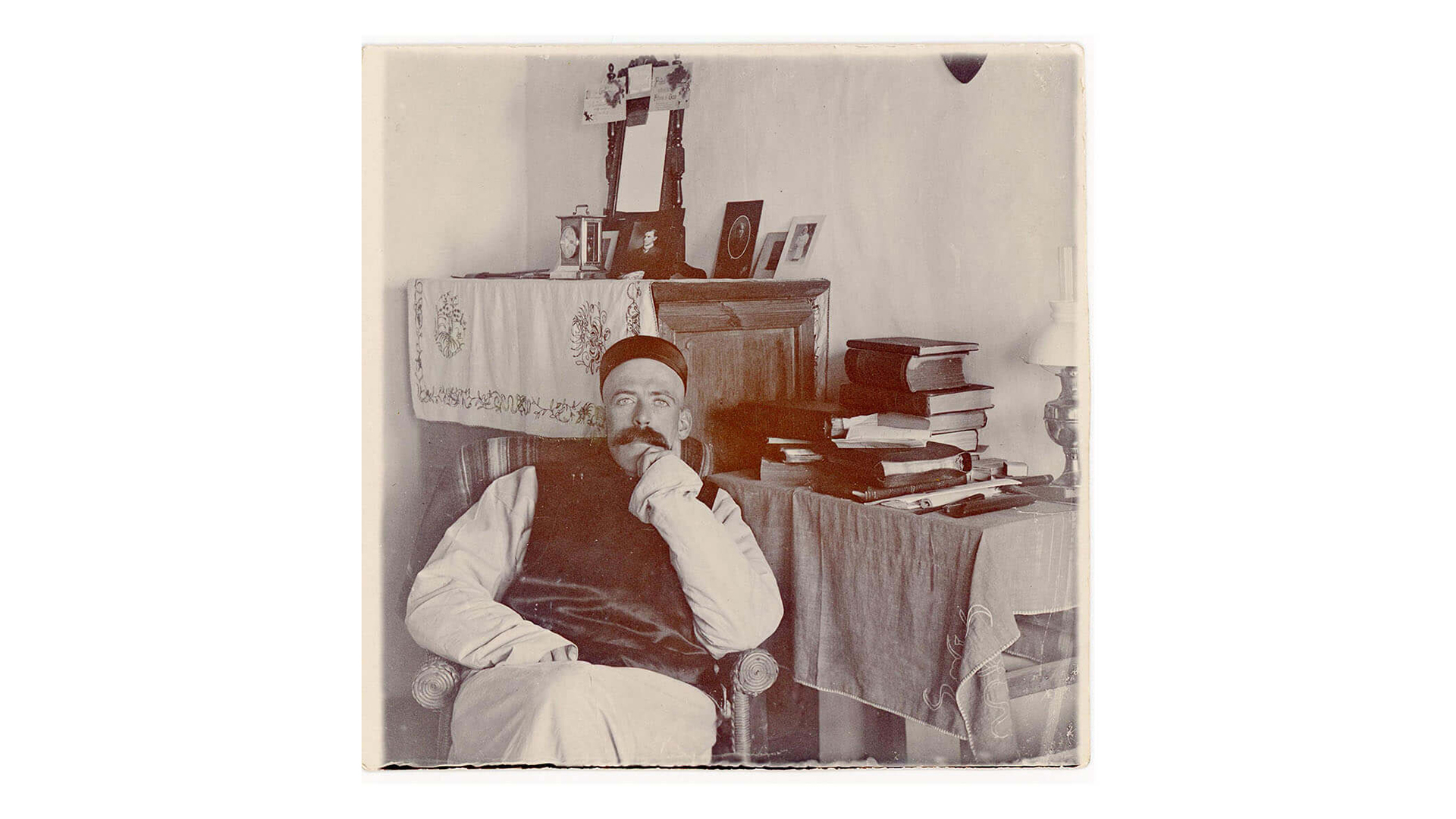

Dr. Clark was an avid photographer and we have around 370 black & white photographs taken by him. Many of these include handwritten annotations in pencil on the reverse, though according to the family, most of the notes were made by his wife.

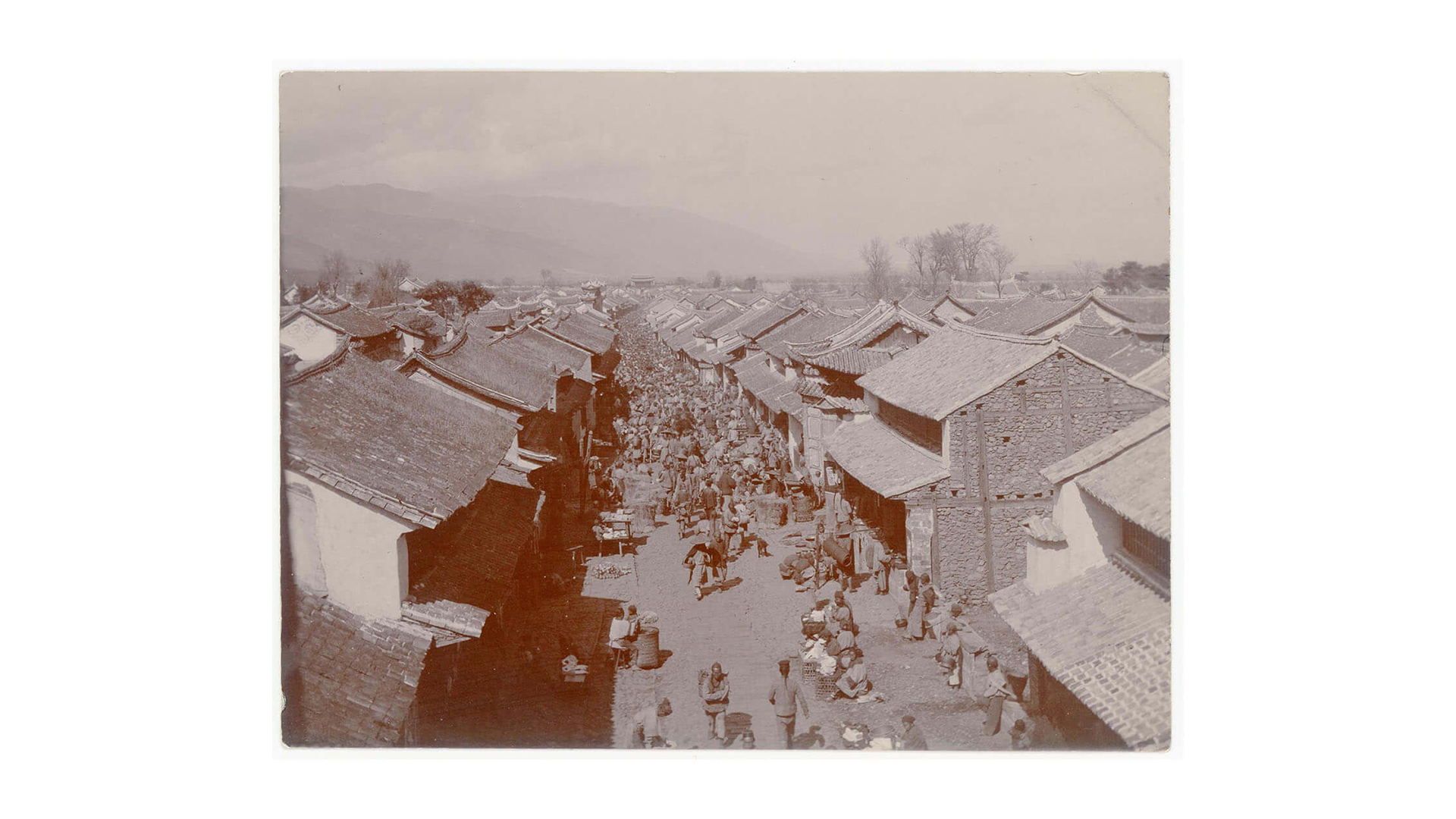

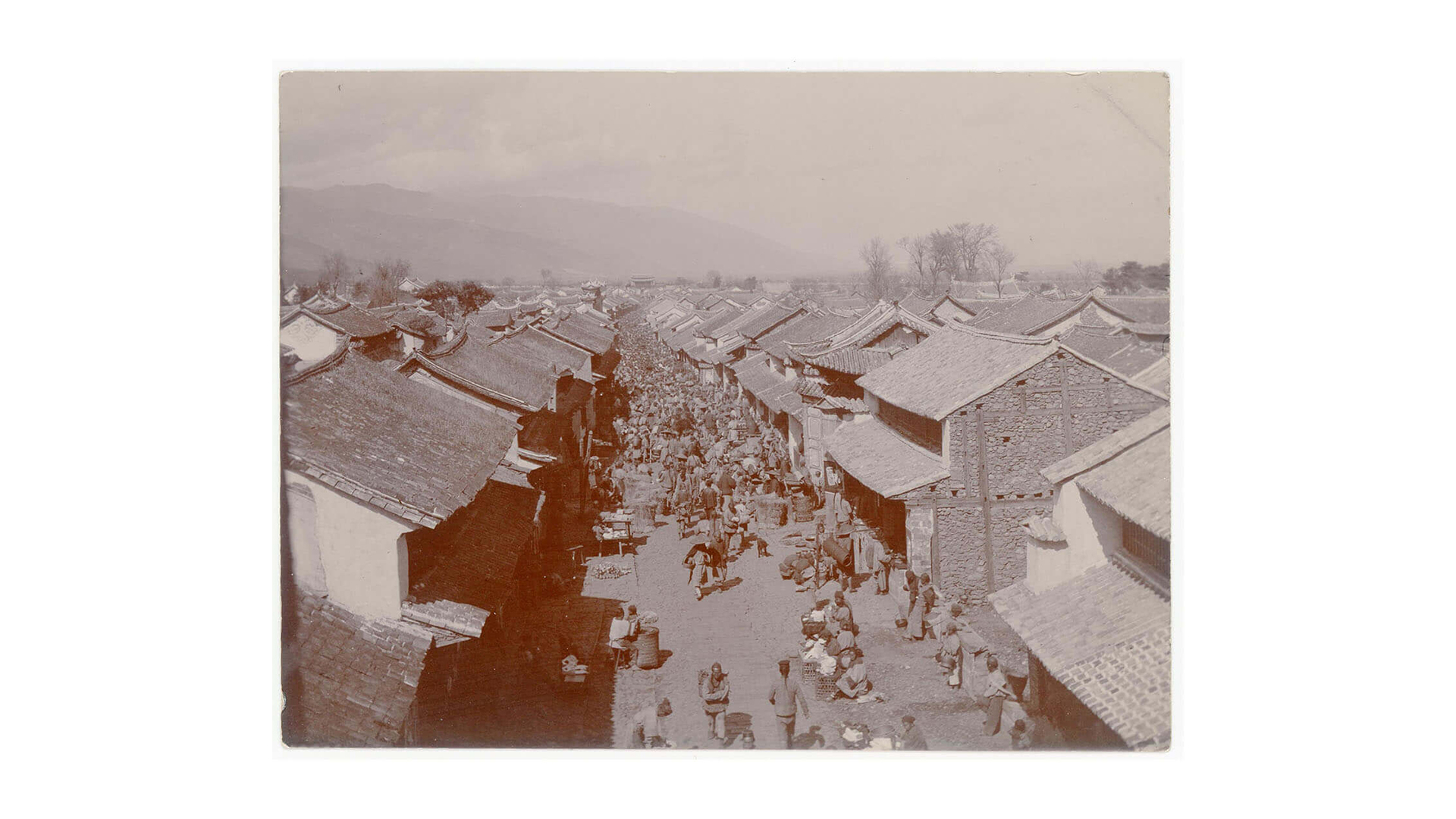

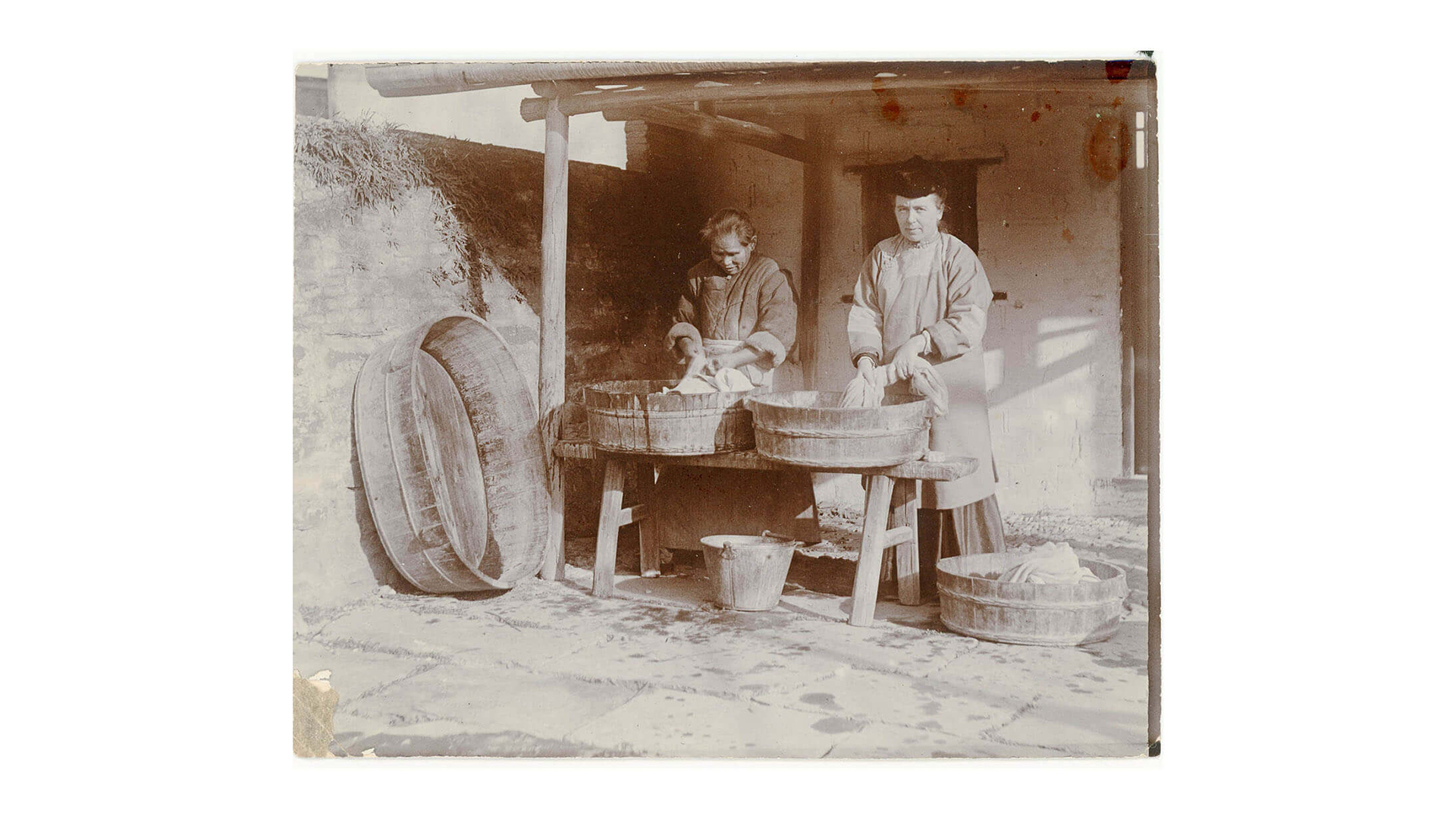

The photos include a wide range of subjects, such as cityscape, landscape, riverscape, local people, and missionaries. A large portion concentrates on images of ethnic minority groups in Yunnan province.

Dr. Clark, who primarily provided medical assistance to local people and helped organize Sunday services, must have gained the trust of these sitters who let a foreigner photograph them.

The work among the tribespeople, whose customs and religious holds were different from the Han-Chinese as keenly noted by him, were not comparable with the Mission’s work in other locations. He told his mother what happened in China in the big coastal cities did not seem to affect a place that was some 2,000 miles away. In fact, he considered himself lucky to not be living in a major metropolitan area. His contentment is revealed in the picturesque window view of his room captured by his camera, his lively descriptions of flowering trees bearing clusters of pink flowers, and of occasional outings in the mountains that brought him a magnificent view of the city and plain.

From the many letters we find out that life was certainly busy for Dr. Clark in Dali. At one point, he reported seeing between 30 and 40 patients daily. According to missionary records, he treated 2,878 patients in one year (1905), of whom 780 were women. In one letter, he proudly writes about a successful operation of a “hare lip” on the daughter of District Magistrate.

Although local people saw him as a medical doctor who could help them, Dr. Clark wished for more time to work on his church services. In the late summer of 1907, he mentioned going to a “big market” where people came after undertaking a six-to-eight-day journey from every direction to trade in the villages. By taking a “hua kan” (a seat between two poles carried by two men) and hiring a local laborer to carry the load of books, sheet tracts etc., he reached the place in three days. The journey was often grueling and exhausting, with Dr. Clark having to spend some nights camped out under the stars. During his two-day stay at the “big market,” he managed to set up a stall and sell a hundred copies of portions of the gospels and scripture, miscellaneous religious books, sheet tracts, and a few dozen almanacs and calendars. People would stop by to have a look at him apparently out of curiosity, which then, according to Dr. Clark, gave them “a chance to see what I am selling.”

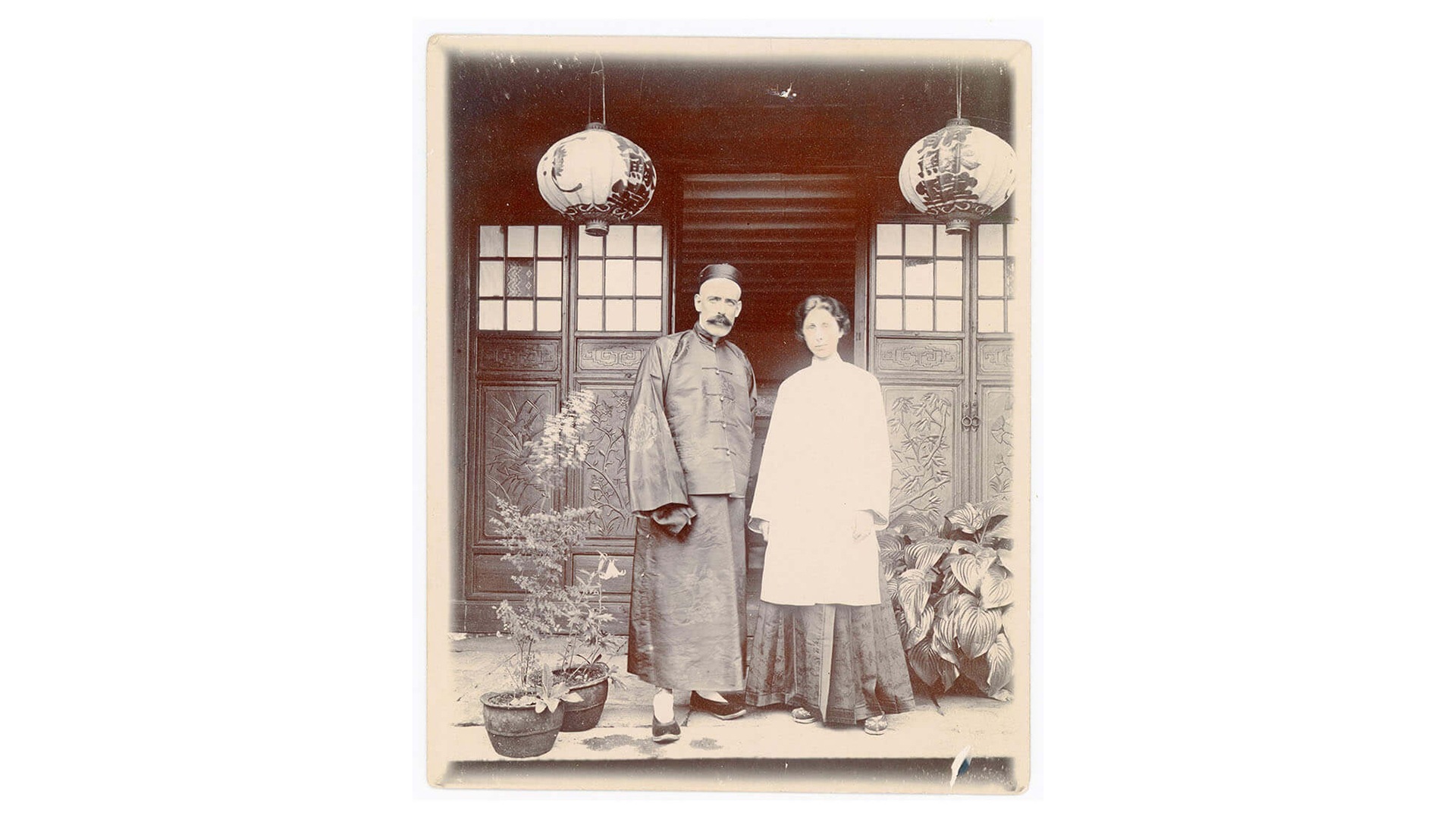

CIM was known for regulating its missionaries to not only learn the Chinese language, but also wear Chinese dress and live among the local people to instill Christianity into Chinese society. Clark felt comfortable in his “thin blue silk gown” as he wrote to his mother in 1907 when the rule regarding dress was rescinded.

Many of his photos show him, his wife, and other missionaries living in Chinese compounds and interacting with the locals. Unlike those missionaries who preferred to live entirely on foreign goods provided by import stores, he seemed to enjoy Chinese food. He talked about how salty meat and fish grew on him and admitted that “Chinese food is really much tastier than foreign food.”

In one of his letters Clark mentioned that the “Foreigner is always a source of endless curiosity to the Chinese.” He must have shared a similar curiosity as he eagerly recorded the people and the land he came to serve in his photos. But his religious mission and faith may have prevented him from exploring this foreign country more deeply without biases. In his view, the local people’s belief in “idolatry” had a strong hold upon them, and he criticized that the major belief systems in China, such as Confucianism, Buddhism, and Taoism, taught nothing about “a change of heart.”

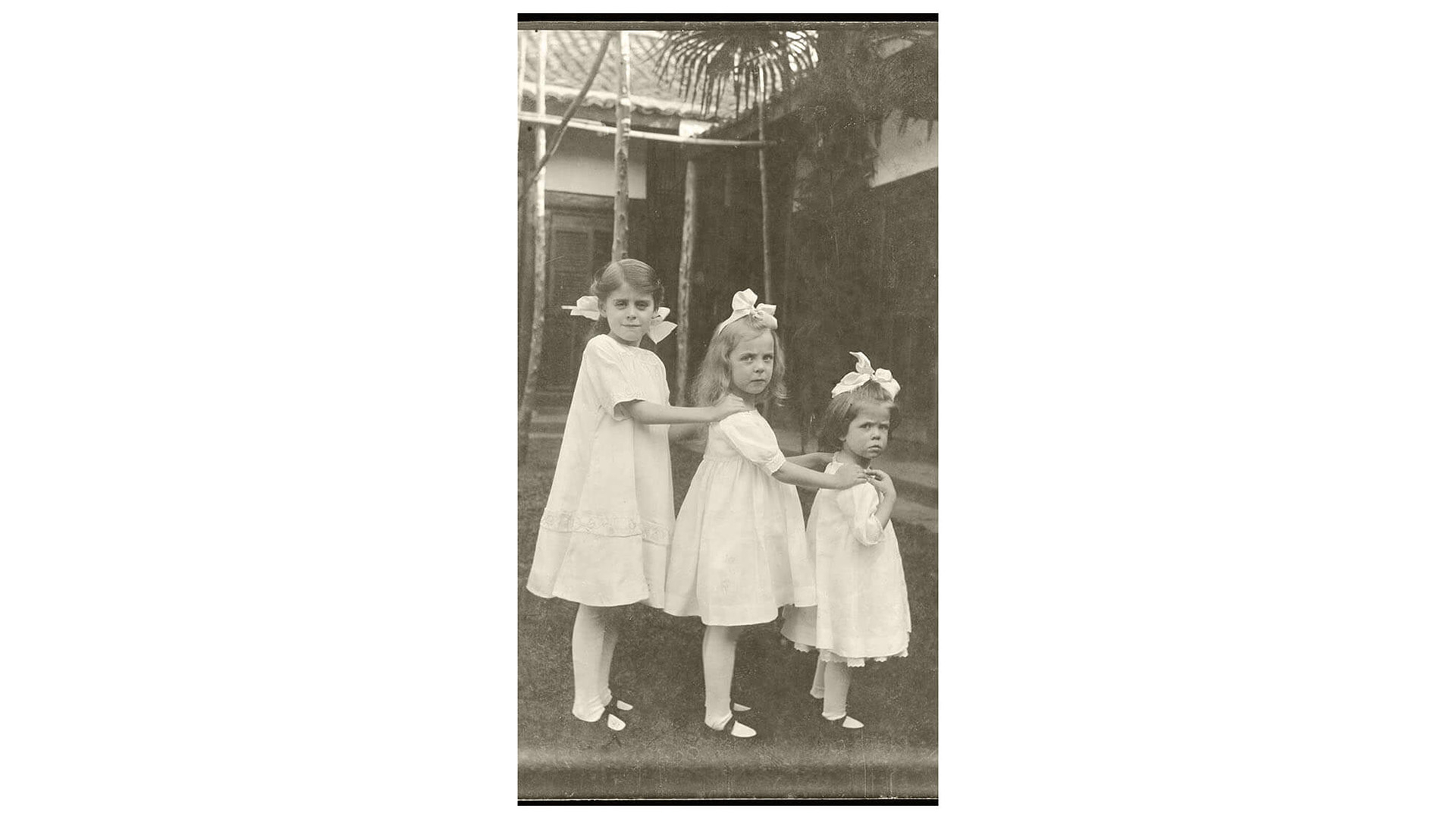

Dr. Clark was a single man during most of his time in Dali until 1908. He and his future wife Ethelwyn Naylor (Wynnie, as she was known to her family), who worked at the Shanghai CIM head office, travelled to Bhamo in Upper Burma (at the time British territory), to legally get married. Their first child was born in Dali before they went back to Canada on furlough in 1910. Then they were stationed in Baoning, Sichuan province and remained there until 1917. While most of the surviving letters are from his earlier Yunnan period, his photos document their life in Baoning (photos of his three daughters and the hospital “Renji yiyuan”).

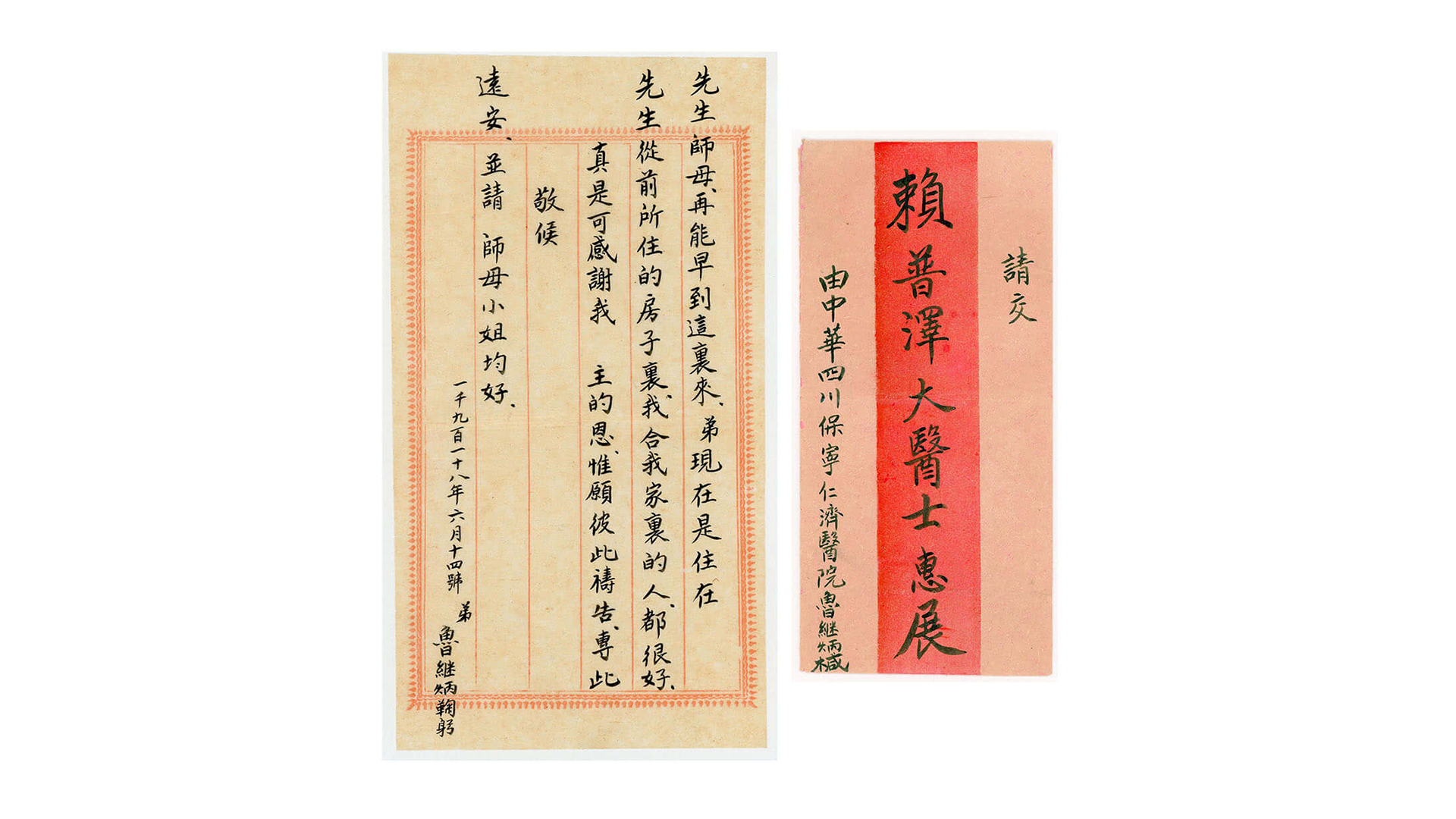

Remarkably, the Clark family preserved several handwritten letters in Chinese that are addressed to Dr. Lai Puzhe (Clark’s Chinese Christian name), sent by the “Chinese helpers” from the hospital at Baoning to Canada. These personal letters give us a glimpse into what is often missing in a Canadian missionary’s narrative: the voice of the Chinese, with whom the Clark family had built a sincere friendship. After all, the path of encountering others is never one-sided. And, within today’s world of rapid communication, this collection of letters and photographs stand as a historical record, giving us an incomparable window into the past.

With special thanks to Patricia Kennedy for sharing with me insights and information on her grandparents.