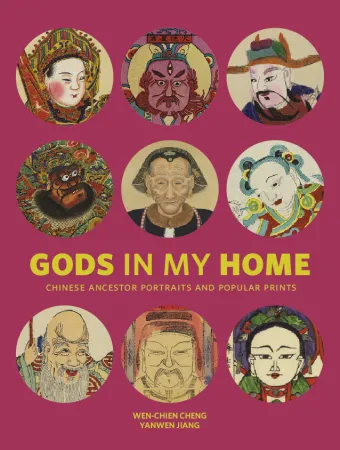

Gods in My Home: Chinese Ancestor Portraits and Popular Prints

Gods in My Home: Chinese Ancestor Portraits and Popular Prints

-

Categories

Art & Culture

-

Publisher

ROM

- Publication Year 2019

-

Size

9" x 12"

-

Pages

208

-

Format

Soft Cover

-

ISBN

978-0-88854-525-1

-

Price

$50.00

- Author

About the Book

Gods in My Home combines ancestral paintings with traditional popular prints and examines the unexplored connection between these two seemingly separate genres in the context of Chinese Lunar New Year. The images reflect a Chinese view of reverence and the belief that portraits and prints were capable of blessing and protecting the prosperity of family lines. Featuring a wide array of prints and paintings, ancestral portraits, and paper gods, the book explores shared family values, ritual concepts, belief in visual powers, and shared traditions. The publication studies the artworks through the lens of their unique status as images used for domestic worship of popular gods and ancestors in regular households during the late imperial and early Republic periods.

This book is the first study that explores the underlying themes and connections between ancestor portraits and popular prints. It provides insights into how these images reflect a view of the domestic, material, and spiritual life of Chinese society.