Picnics and Pastimes

Objects from 17th-century Iran offer a glimpse into life during the Safavid dynasty

A new installation at ROM highlights

A new installation at ROM highlights intricate objects that offer a window into the pleasures, pastimes, and artistic heritage of Iran during the Safavid dynasty (1501–1736). The Safavids, a Shi’a Muslim dynasty, were great patrons of the arts and architecture and fostered international trade and diplomacy from their newly built capital city, Isfahan, in central Iran. A popular Persian saying dating back to the 17th century, esfahan nesf-e jahan (Isfahan is half the world), captures the cultural vibrancy and cosmopolitan nature of this bustling city. Isfahan is famous for its architecture, with grand boulevards, gardens, palaces, and coffee houses, alongside beautifully tiled mosques, churches, and synagogues. The focus of the display is a spectacular ceramic-tiled arch, made around 1685–1695 in Isfahan, which depicts a group of fashionably dressed noblemen picnicking in a meadow of flowers and trees. ROM researchers Lisa Golombek and Robert B. Mason have spent many years studying and digitally reconstructing Safavid tile arches. They propose that ROM’s arch was one of over 50 others that were made specifically to decorate the walls inside an enclosed palace garden during the Safavid period. Their fascinating research will soon be published in a new book, Princes, Dervishes and Dragons: The Tile Arcade from Safavid Isfahan (c. 1685–95) (Edinburgh University Press, 2025).

In it, they convincingly argue that ROM’s tile arch and over 50 others with different narrative scenes probably flanked a long, narrow garden with a grand pavilion called the Talar-e-Tavileh (Pavilion of the Stables), which was used by the Safavids to host New Year celebrations, court ceremonies, religious festivals, and diplomatic banquets. The building fell into disuse in the 19th century and was finally torn down in 1901 after its numerous tiled archways were sold on the art market. ROM’s tile arch has been reassembled with 38 original tiles and four carefully repainted reproductions, while the plain yellow tiles at the centre replace missing pieces. Creating an arch of this size and detail required great artistic skill and expense. First, clay tiles made in moulds were covered in an opaque white glaze and fired in a kiln. Then, drawings on paper were stencilled onto the tiles by sprinkling charcoal through small holes outlining the design. The workshop’s master painted the outlines of the stencilled design using a greasy black pigment that prevented the coloured glazes from bleeding into one another. Artisans carefully applied different coloured glazes within the outlines, and the tiles were fired once more. Finer details, such as facial features and hair, were painted with the same black pigment by the master using a fine brush, and then, the tile was fired one last time at a lower temperature.

The Safavids, a Shi’a Muslim dynasty, were great patrons of the arts and architecture and fostered international trade and diplomacy from their newly built capital city, Isfahan, in central Iran.

he scene on the tile arch features live music and, by extension, poetic recitations, creating a multi-sensory ambience

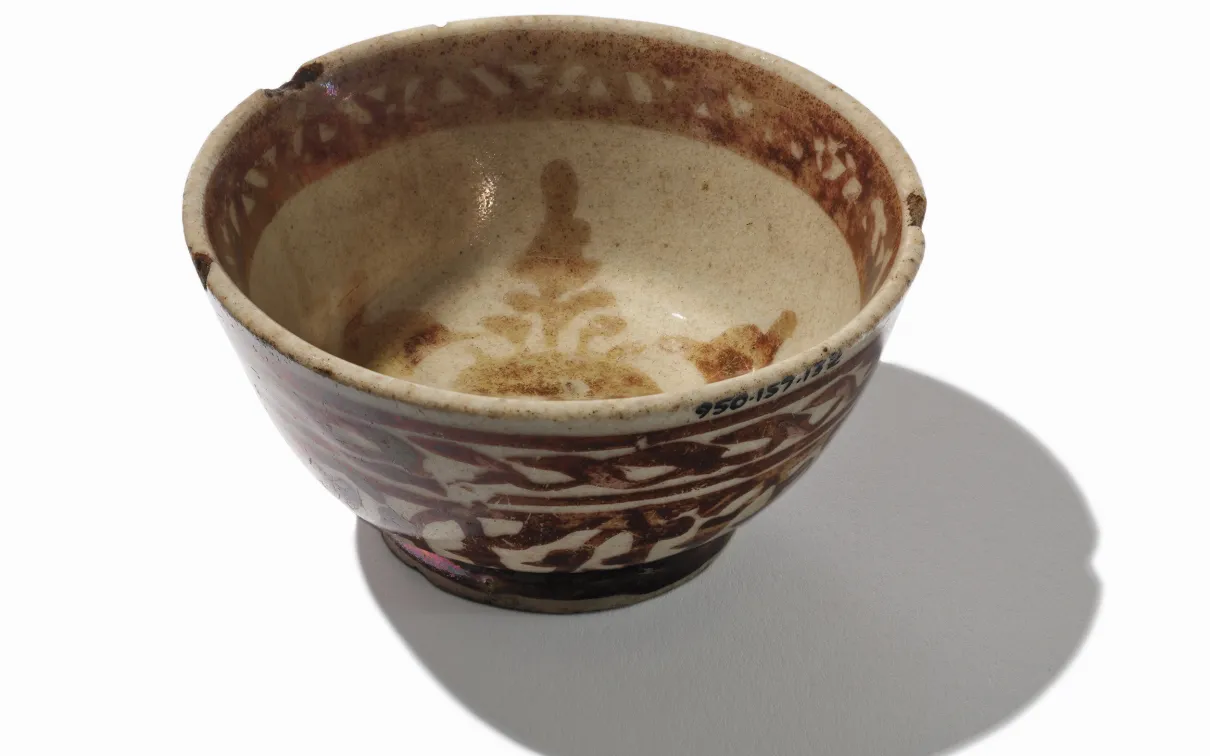

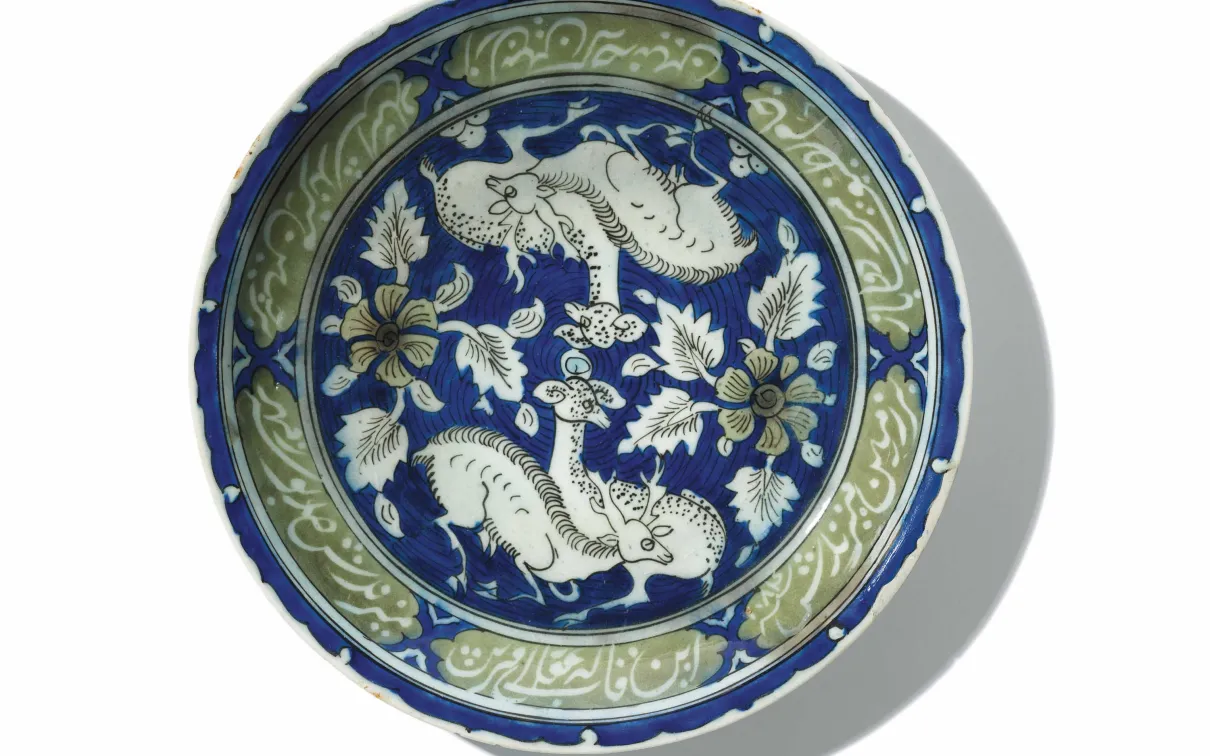

The scene on the tile arch features live music and, by extension, poetic recitations, creating a multi-sensory ambience. Safavid eating and drinking vessels were often inscribed with verses that invoked blessings upon guests. A large punch bowl proclaims “May every sip you taste from this bowl bring you good health,” while a Chinese-inspired blue-and-white dish with deer features poetry from the renowned medieval scholar Omar Khayyam (1048–1131) beginning with the lines “This dish, which the intellect applauds, and on whose forehead it places a hundred kisses!” Around 1627–1629, Thomas Herbert, an English traveller, visited Safavid Iran. In Isfahan, he tasted coffee for the very first time at a coffee house and described it as “black as soot, thick and strong scented, that pleased neither the eye nor taste.” The coffee was served in small ceramic cups, like the one on display. Coffee was also enjoyed at picnics, but before the 1500s, no one in the world had tasted coffee except for the people of Yemen and Ethiopia, from where it originated and later spread around the world.

Near the bottom of the arch, two musicians sit cross-legged, with one playing a round framed drum (daff) and the other holding a stringed instrument (kamancheh) in his lap.

Near the bottom of the arch, two musicians sit cross-legged, with one playing a round framed drum (daff) and the other holding a stringed instrument (kamancheh) in his lap. While not shown on the arch, we have in the Museum’s collections a long-necked lute from the early Safavid period. Called a panjtar (lit - erally “five strings”), the lute was made from several types of wood and sumptuously inlaid with mother-of-pearl, ivory, and bone with images of elephants and scenes of hounds and lions on the hunt.

The royal pursuits of feasting (bazm) and fighting (razm ) are often paired in Iranian art and literature. By extension, a good warrior must also be a skilled hunter. These themes are referenced on the tile arch as a man with an impressive moustache extends his bow and arrow toward a bird in flight (see detail on p. 17). Hunting parties were typically followed by outdoor banquets. The immaculately dressed seated figures shown on the arch are seated in repose as they are served delicious food and drink while being entertained with music and feats of archery. The display provides a glimpse into the pastimes enjoyed by people in 17th-cen - tury Iran and the rich artistic legacy of the Safavid era.

Picnics and Pastimes

Picnics and Pastimes will be on display beginning November 16, 2024, on the main floor of the Museum. These objects and other parts of ROM’s Islamic World collections will be displayed in a future gallery as part of the Museum’s OpenROM transformation.

Dr. Fahmida Suleman is Senior Curator of the Islamic World collection at ROM