The Magnificent ROM Mosaic Ceiling

Published

Category

Author

the first large-scale mosaic in Canada produced by a Canadian company

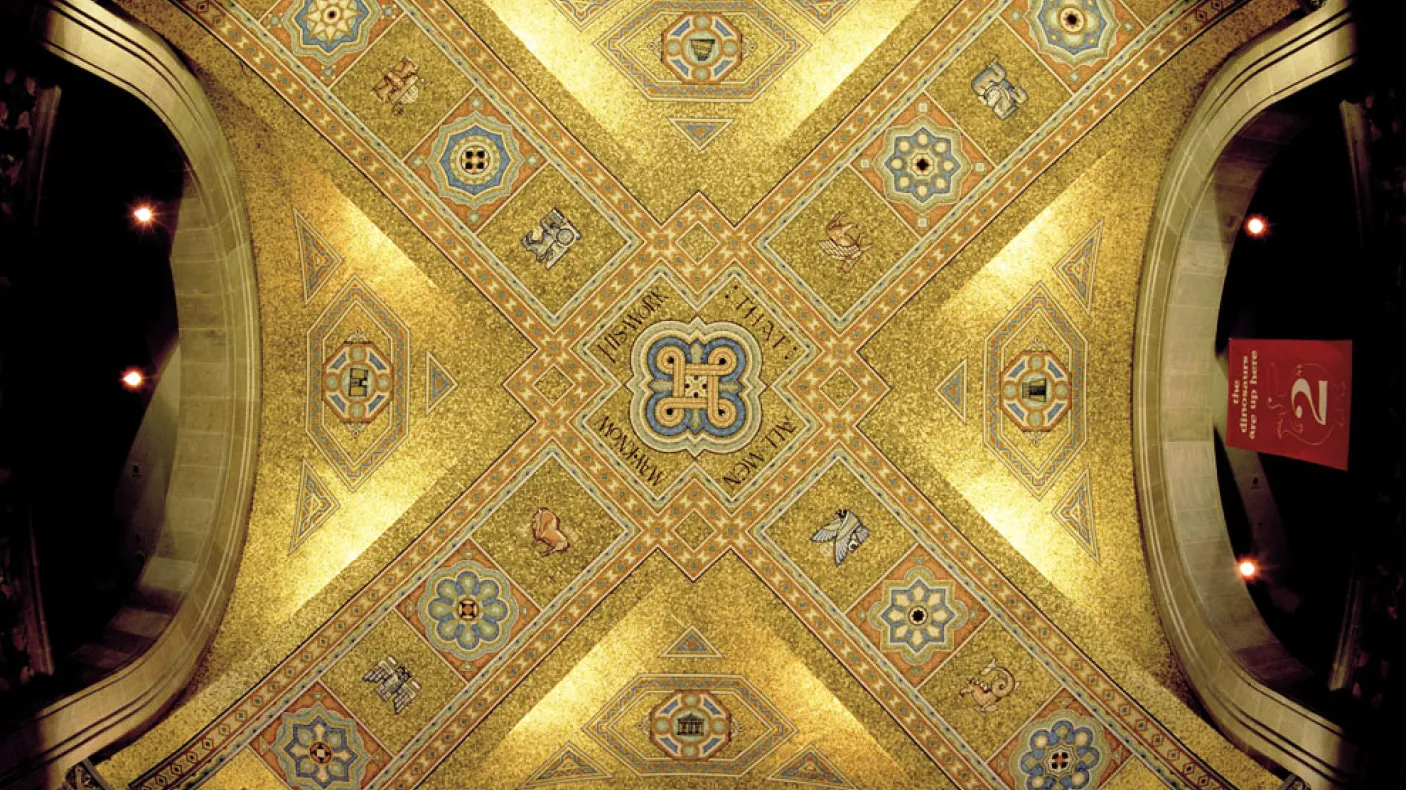

As the first large-scale mosaic in Canada produced by a Canadian company, the magnificent ROM mosaic is much admired. With brightly coloured figures standing out against a glittering gold background, reflecting the Byzantine style of mosaics found in Venice, it bears a universal message that goes beyond the single-themed mosaic works of art found elsewhere. Encyclopedic, like the museum it adorns, the mosaic is said to express “unity in diversity.”

In 1933, a new wing was added to ROM, with the mosaic gracing the vaulted ceiling above the Rotunda entrance. The architectural firm Chapman and Oxley designed the new wing of the museum in the Beaux-arts classical style of the day. The contract for the mosaic was awarded to the newly established Connolly Marble, Mosaic and Tile Company, which advertised among its offerings special Venetian mosaics. The Connolly company letters in ROM’s archives explain how the materials (premier-quality vitreous tiles or smalti) were imported from Italy, probably Venice, and the tiles were cut into tesserae, before being mounted and glue-pasted in the Toronto workshop by “skilled Italian craftsmen.”

There has been some discussion as to who designed the mosaic with its symbols of the civilizations of the world from the early ages of the Indigenous peoples of the Americas through to the European Middle Ages, the latter seen as the culmination of art when the Byzantine style prevailed. It might have been the idea of Dr. Charles Trick Currelly, a University of Toronto archaeologist and one of ROM’s founders. Yet no one ever claimed authorship of the design. The Connolly documentation refers to the “architect and designer” and to changes in design and colour scheme necessitated when the solid gold background was ultimately chosen. It is most probable that the design emanated from the studio of the architect Alfred H. Chapman, who had studied for two years at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. However, since the original plan was modified, the final product may have been a collaborative effort, as was the central design bearing the Biblical inscription. Input from the mosaicists themselves is a real possibility.

But another fundamental question remained: who exactly were the artisans from Italy who executed the mosaic in the Connolly workshop at 235 College Street? Serendipity led me and Dr. Angelo Principe, my co-researcher at the time, to some fascinating discoveries. In the mid-1990s, while studying a segment of the Italian community in Toronto originating from the Friuli region in the north-east corner of the Italian peninsula, and the founding of their association, called the Famee Furlane (Friulian Family), in the early 1930s, we discovered that many of these new Canadians were active in the marble, mosaic, and terrazzo business. Some of the survivors and many of their descendants told us stories about their own and their ancestors’ contribution to mosaic masterpieces, including the ROM mosaic and the Thomas Foster Memorial of Uxbridge, Ontario, the latter a Byzantine-style temple with rich mosaic installations provided by the same Connolly company. Their oral testimony, and the documentation they provided, including photographs taken on the site of the Foster Memorial, were to provide clues—all to be confirmed by further archival research. One eye witness, involved in the installation of the mosaic, had testified that there were three or four craftsmen working in the shop. My personal research led to the identification of three mosaic craftsmen, along with other protagonists in the ROM mosaic project.

My examination of passenger arrival lists and Washington directories filled in the story of Ciro Mora and helped rescue him from obscurity.

The Chief Mosaicist

By consulting the Might’s Toronto directories, I was able to uncover the names of the officers of the Connolly company. By 1930 Joseph P. Connolly (Drogheda, Ireland 1882–Toronto 1943), who had previously worked for other Italian-run companies in Toronto, was president of his own newly formed company. Connolly’s partners were Ciro Mora (Sequals, Italy 1889–1960) and Antonio Bortuzzo (Spilimbergo, Italy 1880-1966). Bortuzzo was from the town where the School for Mosaicists was established in 1922. On-location interviews with his family members in Spilimbergo also revealed Bortuzzo’s nickname as “double Tony,” stemming from his capacity to do the work of two men.

Connolly’s other partner, Ciro Mora, turned out to have been the chief mosaicist directing work on both the ROM and the Foster Memorial sites. Articles of the day, in both the local English- and Italian-language press, had reported on his achievements. A piece from the Toronto Daily Star (19 April 1929) announced the arrival in Toronto of mosaicist Ciro Mora, “possibly […] the only man to-day in the Dominion [of Canada] capable of reproducing the ancient Roman mosaic work in all its original beauty.” It explained the extensive preparation of artisans such as Mora (consisting of four years of training plus a long apprenticeship); announced that he was about to execute the mosaic entrance to the Concourse Building (now EY Tower), designed by Group of Seven artist James E.H. MacDonald; and reported, at least three years before the ROM mosaic was to become a reality, that Mora was then dealing with the museum. After the completion of the Foster Memorial in 1936, two articles appeared in a local Italian-language newspaper praising Mora as the person responsible for both the Foster Memorial and the ROM mosaics.

My examination of passenger arrival lists and Washington directories filled in the story of Ciro Mora and helped rescue him from obscurity. Mora hailed from Sequals, a town in Friuli where a centuries-long tradition of terrazzo and mosaic existed.

The local specialty is believed to have resulted from the ingenuity of the inhabitants who exploited the stony terrain, turning the stones into artistically designed flooring and mastering the art of mosaic which the countless emigrants from the area were to take with them all over Europe and to North America.

After leaving Europe himself, and before coming to Canada in 1926, Mora had immigrated to the US. In Washington, he was employed by a family member who ran the National Mosaic Company responsible for government buildings there. In Toronto, Mora worked with other companies and, in 1930, became a partner in Connolly’s newly formed company. His early association with Connolly and the ROM leads one to wonder whether he could have instigated the felicitous change to a golden background for the Rotunda mosaic.

Joseph P. Connelly

Craft and craftsmen

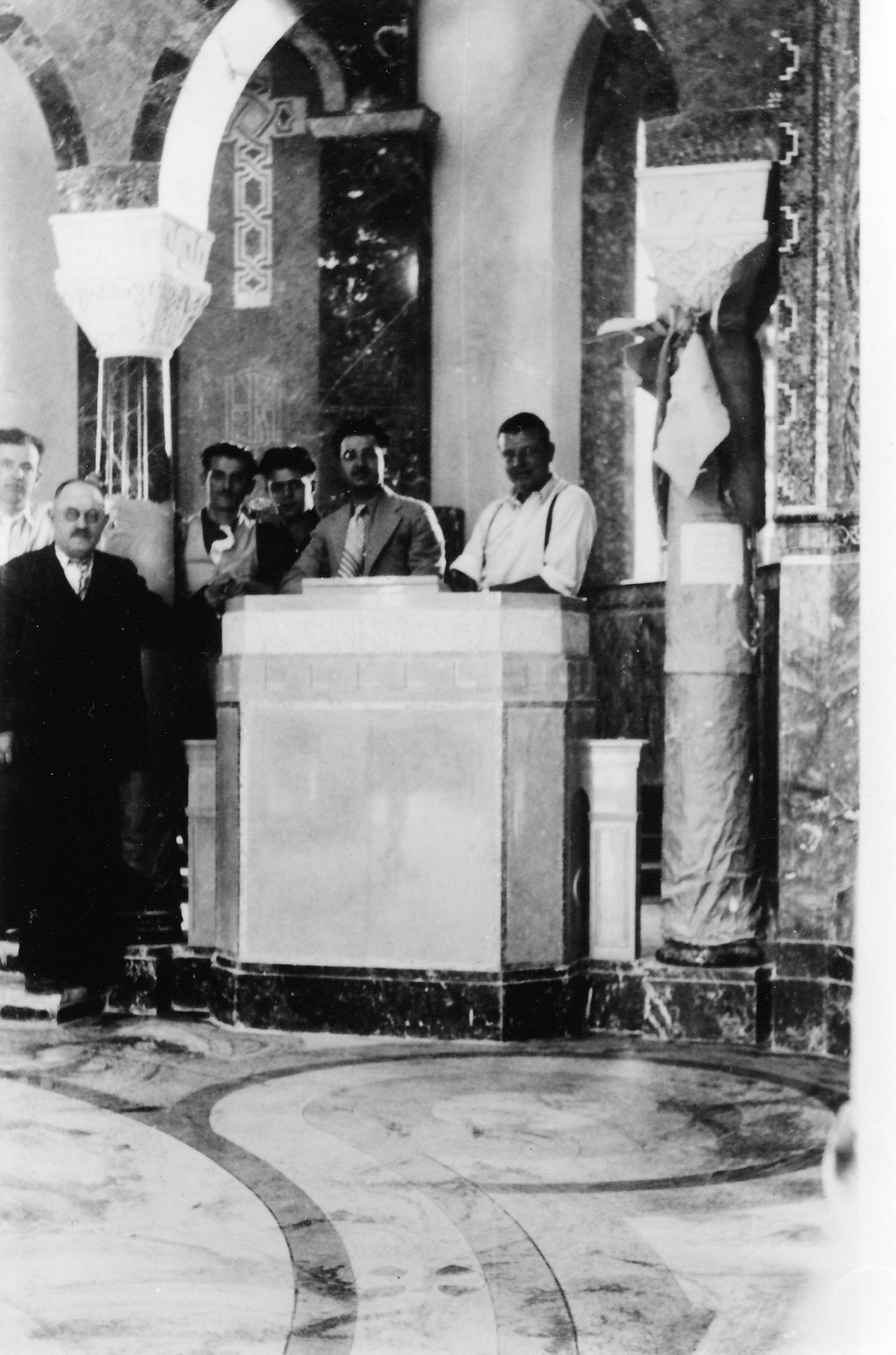

Photographs produced and interpreted by persons interviewed brought about the identification of a second craftsman who contributed to the execution of the ROM and Foster Memorial mosaics. Antonio Dell’Angela (Pozzecco di Bertiolo, Italy 1875–San Vito al Tagliamento, Italy, 1948), an award-winning mosaicist, recognized for his achievements in Venetian-styled mosaic art, was invited to work in the US. In Canada, he contributed to the ROM mosaic as supervising mosaicist. In a group photograph taken inside the Foster Memorial in 1936, he appears as the older authoritative-looking figure in the foreground. As daughter Elsa Dell’Angela Bratti told me in an interview, it recorded a festive occasion that she too had attended as a young woman. As the senior Dell’Angela informed the Italian press (14 August 1936), probably as a Connolly spokesperson, the picnic for the workers’ families had taken place on the previous Sunday (9 August), undoubtedly in the Friulian tradition of celebrating the completion of a building, and also as a manifestation of former Toronto mayor Foster’s philanthropy.

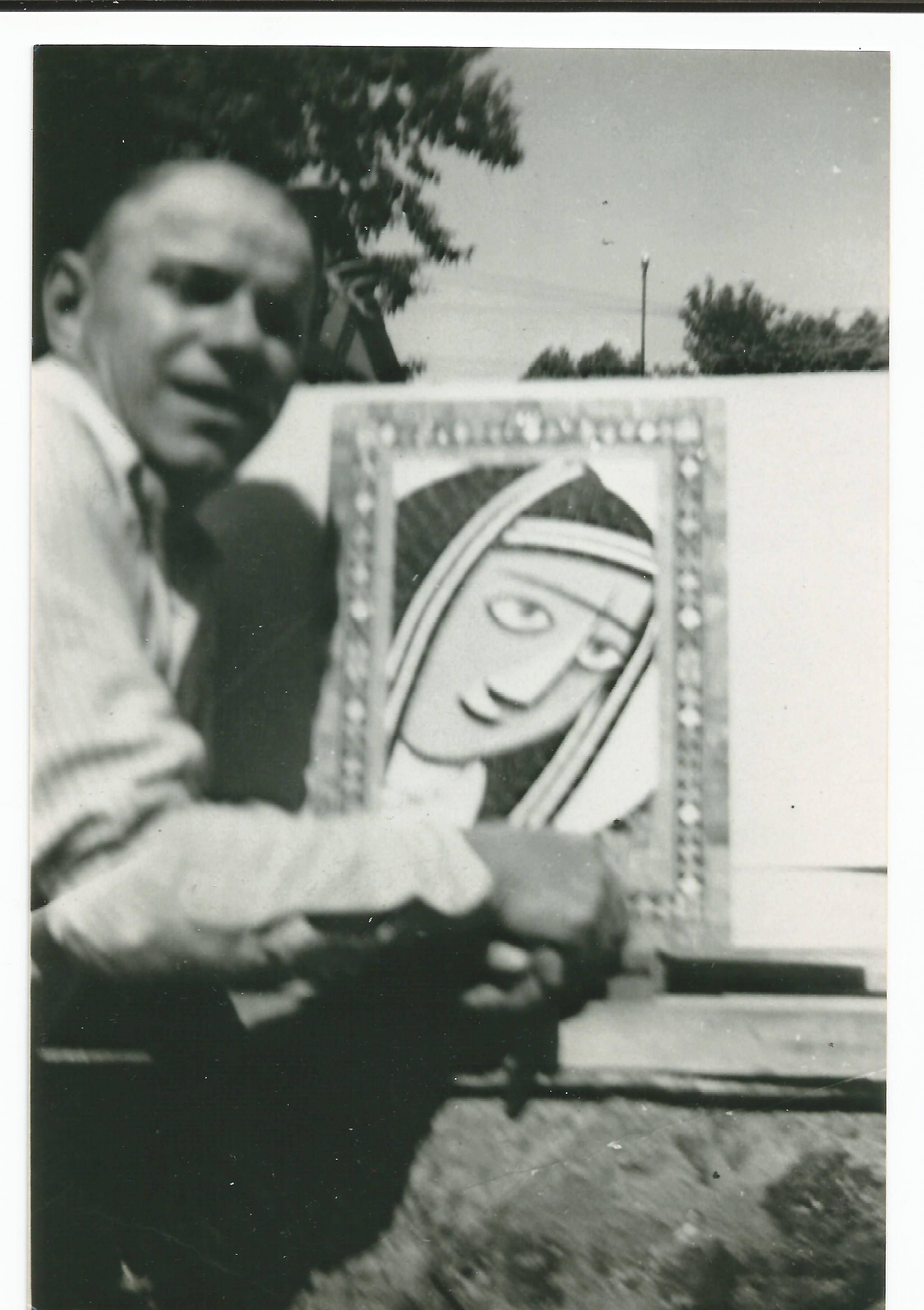

The third craftsman was discovered when members of the Italian community, being interviewed, recalled the excitement that had existed over their compatriots’ work on the ROM mosaic. They directed me to the family of Marino Colonello (San Giovanni di Casarsa, Italy 1903–Toronto 1979), a Spilimbergo-trained mosaicist of a younger generation, who arrived in Canada in 1926 and certainly ‘left his mark’. Daughter Marina Colonello Pezzetta explained how her father had proudly taken his family to the museum to see the masterpiece on which he had collaborated. Moreover, he confided that he had inserted some personal touches in it. Indeed, many of his works bear his initials. I was able to verify that Marino Colonello’s initials are found in the mosaic terrazzo floor of the 1951 New City Hall in Peterborough (ON) depicting a map of the district surrounding the city. This is not an unusual practice. The sculptors, who worked on Toronto Old City Hall, are known to have carved the faces of real persons in the gargoyles, and in St. Anne’s Anglican Church, a Group of Seven artist painted his own facial features in a figure in one of the religious scenes, now lost in the June fire.

A search for evidence of something comparable in the ROM mosaic led to a re-examination of the depiction of the Lion of St. Mark. Aside from the Biblical inscription at the centre of the vaulted ceiling, it is the only panel of twelve displaying lettering. M-A-R is the first syllable of the name MAR-CUS, of course. In traditional iconography, when space was limited, parts of any word could appear on separate lines. But where is the rest of the saint’s name in this case? Marino Colonello may intentionally have left it incomplete, citing lack of space, or he may have inserted the three slanted letters on his own initiative, discreetly suggesting not only the saint’s name, but also his own.

Colonello images

Pride of Place

The last group of contributors to the ROM mosaic are the De Carli brothers. Olvino De Carli (Arba, Italy 1912–Toronto 1997) had explained during several interviews, and photographs provided by the De Carli family proved, that he and his older brother Remo (Arba, Italy 1908–Toronto 1972) were among those who installed the ROM mosaic. One family-owned photograph, reproduced in a Telegram newspaper article (2 June 1962), shows the two brothers visiting the ROM mosaic on the 50th anniversary of the founding of the museum. Under their leadership, as the new owners, and with brother Antonio (Arba, Italy 1910-Toronto 1973) serving in a managerial role, the Connolly company was to furnish much embellishment on architectural sites not just in the Toronto area but in other provinces of Canada too.

The addition of new characters and events to the story of ROM’s mosaic proves that Italian culture has pride of place in it, not only in the overall design of the work and in some of its details (two out of 12 panels represent Rome and Venice), but also because it is the creation of skilled artisans, originally from Italy, who executed the work and brought it to life in a Toronto workshop.

On 23 June 2024, Professor Emerita Olga Zorzi Pugliese gave a talk, titled “Italian Creativity and Heritage in Toronto: The ROM (Royal Ontario Museum) Mosaic of 1933,” at ROM. It was part of Italian Heritage Month sponsored by the Consulate General of Italy and the Italian Cultural Institute in Toronto, in partnership with the ROM. During her decades-long research, Professor Pugliese has identified approximately 200 mosaic works of art throughout Canada, and has published widely on the topic. Two of her articles focussing on the ROM mosaic appeared in 2004 and 2021.