Porcelain Histories

Published

Category

Author

Porcelain Histories

ROM recently acquired two artworks by Heidi McKenzie that function in critical dialogue with each other about the history of Indian indentured labour in the Caribbean. They engage with the history of indenture without reproducing the forms of violence perpetrated by colonial ethnographic-type images. Instead, the insertion of McKenzie’s family history into the works makes an intervention that humanizes the subjects depicted.

After the abolishment of African slavery in the British empire in 1833, alternative forms of inexpensive labour were coerced to work the plantations growing lucrative commodities like cotton and sugar in Britain’s various colonies. A system of indenture was established in which poor, marginalized, or in some manner compromised people from one part of the British empire were brought to another part of the empire to work for a low wage. They came hoping for a better life, but the system of indenture, referred to by some as the “new slavery,” forced them into long hours of hard labour, abuse, and hardship that left them further in debt. Few returned and most ended up settling in their new context.

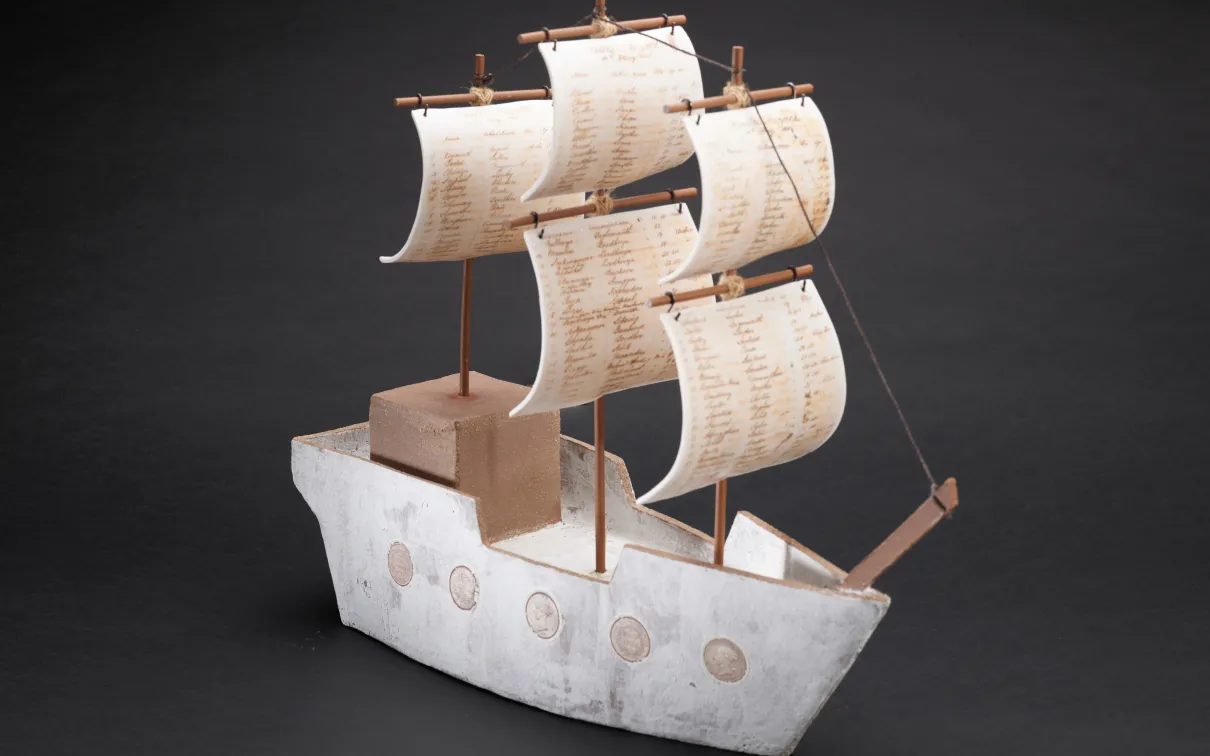

First Wave (2021) references the first ship that brought Indian people to the Caribbean to work as indentured labourers in 1845. This ship, the Fatel Razack or Futtle Rozack, sailed from Calcutta to Trinidad carrying 225 migrants. The handmade porcelain sails hold images showing the names of the passengers from the ship’s manifest, recently released by the Trinidad and Tobago National Archives, which contain a comprehensive record of the Indian migrants who came to Trinidad from 1845 to 1917. McKenzie’s great-great-grandparents on her father’s maternal line were possibly on that ship based on the names listed, but more family history research is required to confirm. Naming the individuals who made that first passage makes them visible and gives them voice, commemorating their presence.

Illuminated (2021) is a set of three LED light boxes in the shape of lanterns with images of “coolie belles,” taken from mass-produced postcards, on handmade porcelain tiles. Women were the minority among the indentured workers. The ones who did come were likely fleeing a difficult situation at home such as prostitution, assault, or widowhood. When they arrived, they were assigned in marriage to a man, most working similar hard labour as the men, or given domestic work. Toward the end of the 19th century, studio photographs were produced of Indo-Caribbean women dressed in elaborate garments and silver jewellery. The photographs were produced by European photographers and widely circulated as postcards for the tourist industry. The women in these photographs came to be known as “coolie belles”—combining “coolie,” a derogatory word for a low-class labourer, and “belles,” referring to a beautiful woman. The “coolie belle” imagery conveyed the Caribbean as an exotic, picturesque location with beautiful, happy, unthreatening locals. The “coolie belle” images selected by McKenzie were sourced from private, public, and online collections. Within this mix, McKenzie has inserted a photo of her great-great-grandmother, Roonia, from her father’s paternal line. By doing so, McKenzie reclaims the “coolie belle” away from an exploitative tourist gaze and back into the familial relationships the women were a part of as individuals.

Interview

On her recent visit to ROM, McKenzie and I chatted about how these two artworks make a decolonial gesture toward reclaiming history through the insertion of family photographs and personal connections.

Your work integrates themes of gender, ancestry, and migration. How do those subjects influence First Wave and Illuminated?

If we start with First Wave, it is literally a representation of the very first ship that landed on the shores of Trinidad. It’s possible that my father’s maternal ancestors were on the Fatel Razack; but names were incorrectly transcribed by the British. What we do know is that my great-great-grandmother Roonia, the woman who sailed from Calcutta to Guyana in 1864, converted to Islam to escape her Hindu low caste. Her son, Jadoo, left Guyana for Trinidad and converted to Christianity, at which point he changed his name from Jadoo to James McKenzie.

My great-great-grandmother’s photo is on one of the lamp panes in Illuminated. When I conceived of the series, I think I might have thought of the title before I made the work. I really wanted to illuminate the lives of the women. I received a digital version of the photograph of my grandmother about 12 years ago through a cousin. That started a whole journey for me. Really just looking at this photograph got me very, very excited. I mean, what are those bangles? What are the rings? What is she wearing? I was also inspired by Gaiutra Bahadur’s book Coolie Woman. I learned all sorts of things reading that book—that I had held false assumptions about these women. I wanted to show their histories. I wanted to give them voice because their voices were taken away.

I find it moving that

I find it moving that, within this grouping of women whose names we’ve lost, you’ve inserted your great-great-grandmother Roonia. What was the inspiration to do that?

You know, when you ask me that question, I feel a visceral feeling in my gut. I think, on the one hand, it was a very intuitive move. But at the same time, it was also a very calculated move. Placing Roonia on this lantern, all of a sudden, kind of crystallized for me my position within the diaspora. I can envision this spinout as almost infinite possibilities of looking at, positioning, and working within the South Asian diaspora, and my father, myself, my grandfather, my grandmother.

First Wave also weaves in similar themes of migration, family, and the history of indenture. Can you talk about your process in making it?

The structure of the boat itself is made from literally playing with cardboard and making templates and figuring out what I wanted. This was followed by slabs of clay. The sails are porcelain and have the manifest of the Fatel Razack. It was a big deal when the government of Trinidad decided to release that manifest to the public—they had never released any of the ships’ manifests before. I was really excited when that happened. The portholes are made with images of British and Indian coins from the year the ship sailed—in 1845. The other reason that I used coins is to underscore the commodification of human labour and trade.

Both works are made up of different kinds of ceramic material. What do you like about working with ceramic?

I am starting to work in multimedia—incorporating video and augmented reality and archival photography—on the wall and not just on ceramics. But ceramics was really my first understanding of who I was as an artist.

I came to art as a mature artist. But I’ve always loved art, and I had started working in the arts. Around my 40th birthday, my parents were downsizing, and my mother, who kept everything, came to our house and handed me an essay that I had written when I was 10 years old. There were three pages of “what I want to do when I grow up.” I had written that I wanted to be a potter. I had even drawn little diagrams and written about why and what it meant to me. Honestly, it was a shazam moment. This is what I was meant to do with my life. And I really just did it. I quit everything and I did it.

What would you say

What would you say are some of the major milestones in the evolution of your artistic practice?

In 2017, I went to Australia for three months because I wanted to mentor with Mitsuo Shoji, whose work is very minimalist. I learned the techniques of how to do the kind of work that I wanted to do. I just sort of pulled some forms out of … I guess my soul and started working with them. I wanted to create something almost primordial that people could respond to on a visceral level, that had some resonance with the diversity of people that live in the lands now known as Canada.

I was really impacted by the terra nullius belief that there were no people here when the Westerners arrived. I spent some time with the Indigenous communities in the interior of Australia. The Indigenous people of Hermannsburg, from the Western Arrernte language group, were painting their stories onto thrown or pinched pots, which partly affected my desire to tell my stories and my family’s own stories.

I started working with photography on clay in 2014. I began photographing my own body or having somebody photograph my body and putting it onto clay. Shortly thereafter, I knew my father’s life was short, so I started documenting him and his body and his life and his stories. And then, when Canada turned 150, I asked myself, where do I fit within the Canadian landscape?

I grew up on the East Coast, and I didn’t have many people around me who looked like me. One story grew into another story and then into another, until I came to the point where I wanted to tell the stories of other Indo-Caribbean peoples. That’s how it kind of snowballed.

Heidi McKenzie (b. 1968) is of Indo-Trinidadian and Irish American heritage and grew up in Fredericton, New Brunswick. She left a successful career in the broadcast industry to pursue ceramics full-time and apprenticed herself to renowned potters in India and Australia. McKenzie’s work has been exhibited in Indonesia, Australia, Ireland, Denmark, Hungary, the U.S., and Canada. Her art can next be seen on display at Workers Arts and Heritage Centre of Hamilton and Gallery 1C03 in Winnipeg in February 2025.

Deepali Dewan is Dan Mishra Curator of Global South Asia at ROM.