Zuul, Destroyer of Shins

Categories

Researcher

Meet Zuul

A new armoured dinosaur! Zuul’s skeleton is one of the most complete ever found for an ankylosaur, and has an amazingly preserved spiky tail and tail club.

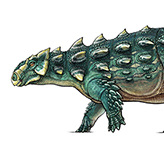

Scientific Name: Zuul crurivastator

Pronunciation: ZOOL (like ‘school’) CRER-eh-vass-TATE-or

Name Meaning: This dinosaur’s short snout, long horns behind the eyes and on the cheeks, and gnarly face resemble Zuul, a fictional monster from the 1984 film Ghostbusters. The species name crurivastator means ‘destroyer of shins’, a reference to its exquisitely preserved sledgehammer-like tail. These powerful tail clubs were unique to ankylosaurine dinosaurs like Zuul, and could inflict serious damage on opponents, such as predatory theropods or maybe even other ankylosaurs competing for mates or territory.

Age: About 75 million years old, from the Campanian Stage of the Late Cretaceous Period

Where it was found: Hill County, Montana, USA

Classification: Dinosauria – Ornithischia – Ankylosauria – Ankylosauridae – Ankylosaurinae – Ankylosaurini

Diet: Plants, likely ferns and shrubs.

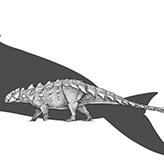

Description: Zuul is an armoured dinosaur. It is a member of the tail-clubbed group Ankylosauridae, and a close relative of the famous Ankylosaurus. It was 6 metres (20 feet) long and weighed more than 2.5 tonnes.

Ankylosaurs had wide, flat bodies, long tails, walked on four legs, and were covered in bony armour. Our new ankylosaur skeleton had four horns on the skull, one behind and one under each eye. It had large nostrils and elaborate ornamentation across the snout. These horns and ornamentation help us to identify different species of ankylosaurs, and showed that this skeleton was, in fact, a new species – Zuul!

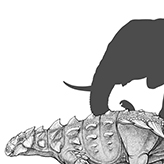

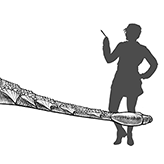

One group of ankylosaurs, called the ankylosaurids, had tail clubs, an amazing biological weapon and one of the weirdest and most recognizable features of ankylosaurs. The back half of the tail was stiff, and the tip of the tail was covered with large bony plates – together, these formed a sledgehammer or axe-like weapon. Zuul has a long tail with sharp, pointed spikes along the sides, and a large tail club.

Gallery

The Science

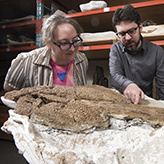

Significance: Zuul is one of the most complete ankylosaurids ever discovered! It is very rare to find a skeleton with both the skull and the tail club preserved together. The bony armour that gives Zuul its spiky appearance (called osteoderms) is part of the skin, which usually rots and falls away from the rest of the skeleton after death. Amazingly, Zuul's skeleton still has these osteoderms in their original positions. Even rarer is that soft tissues along the body are preserved, as well as the horny keratin coverings on many of the tail spikes!

Zuul is the first ankylosaur species named from the Judith River Formation, and good fossils of any dinosaur species are rare in this rock formation. The ROM’s collection of other fossils from the quarry where Zuul was found will help us flesh out the dinosaurs and other plants and animals that shared the same ecosystem, allowing us to recreate and better understand Zuul’s world.

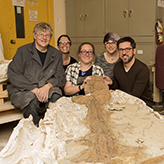

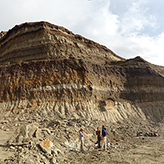

Digging up the Dinosaur: Zuul was found on private land in Havre, Montana. The skeleton was discovered by accident while digging up a meat-eating tyrannosaur skeleton, when a skid loader bumped into its tail club. Zuul was buried under more than 12 metres of rock, and probably wouldn’t have been exposed by natural erosion for thousands of years!

Zuul was found in the Judith River Formation of northern Montana, only 25 km from the Alberta border, in badlands along the Milk River. A ROM team lead by Dr. David Evans has been working these rocks in Alberta for almost 15 years as part of the Southern Alberta Dinosaur Project. Zuul and the other fossils found at this site contribute directly to this long-term ROM research project. ROM palaeontologists have since visited the quarry to collect data on the geology and environment of the world Zuul lived in.

What’s next? Zuul’s skull and tail have been carefully prepared out of the surrounding rocks. Its belly and hips are in a separate block of rock that weighs over 15 tonnes, and will take a few years of careful preparation to reveal the bones, armour, and, hopefully, more skin impressions! The incredible preservation of Zuul’s skeleton gives us the opportunity to use cutting-edge molecular palaeontology techniques to search for original proteins and other organic biomolecules in the soft tissue. We’ll also be using radiometric dating analyses to study the age of Zuul and the surrounding rocks, and will describe the other plants and animals from the quarry that lived in the same ecosystem as Zuul.

Q&A

Want to know more about this incredible new dinosaur?

What kind of food did Zuul eat? Ankylosaurine dinosaurs had wide, toothless beaks, and small, leaf-shaped cheek teeth. Together, this tells us that Zuul was a plant eater, and research on related species of ankylosaurs, like Euoplocephalus from Alberta, suggests that ankylosaurines ate low-growing plants like ferns and shrubs.

Why did ankylosaurs have tail clubs? Tail clubs are definitely one of the weirdest and most recognizable features of ankylosaurs, and Zuul is no exception! Mathematical modeling of tail clubs by Dr. Victoria Arbour has shown that they could smash into things with great force without breaking. Maybe ankylosaurs used their tail clubs to defend themselves from predators like the meat-eating tyrannosaurs, swinging them at their ankles. Or maybe ankylosaurs fought with each other over territory or mates, using their tail clubs like modern deer use their antlers. It’s even possible that ankylosaur tail clubs were used for both defence and offence!

What other animals lived in Zuul’s ecosystem? The plants and animals of the Judith River Formation, where Zuul was found, are still poorly understood even though palaeontologists have been searching for fossils from these rocks for over a century. That’s another reason that Zuul is so special – lots of other fossils were found alongside its skeleton in the same quarry. The ROM collection contains most of these fossils, including an ostrich-like dinosaur (an ornithomimid), adult and baby duck-billed dinosaurs (hadrosaurs), parts of the frill of a horned dinosaur (ceratopsian), teeth from a meat-eating tyrannosaur, skulls and shells from turtles, a crocodile skull, and fossilized leaves. Just like how Zuul represented a new species of ankylosaur (Zuul crurivastator), some of these fossils might prove to be new species as well.

Was Zuul a male or female dinosaur? We don’t know right now if Zuul was a male or female. In very rare instances, palaeontologists can tell if a dinosaur was a female, because they have a cell structure in the limb bones called ‘medullary bone’, which forms right before birds (and dinosaurs!) start to lay eggs. If we don’t see this tissue, it doesn’t mean the dinosaur was male – it could have been a female that wasn’t laying eggs. We haven’t found any limb bones for Zuul yet, but if any are preserved, we’ll be sure to look for medullary bone!

What colour was Zuul? Understanding the colours of extinct animals is an exciting but challenging new area of research in palaeontology. Under the right circumstances, a pigment called melanin can be preserved in fossils, but it can be very difficult to identify with certainty. Melanin in skin, fur, and feathers creates brown, black, and rufous colours. But other colours, like crimson and yellow, are formed by carotenoid pigments that haven’t yet been discovered in fossils, and most blues and greens aren’t created from pigments at all. So far we haven’t found any evidence for preserved pigments in Zuul, so we used inspiration from modern reptiles and birds (and a bit of imagination) to create a colour pattern for our life restoration of Zuul.

When will we be able to see all of Zuul’s skeleton? Zuul’s beautiful skull and amazing tail club are prepared and ready for display. Another block of rock contains Zuul’s hips, belly, and more of its armour. This block weighs over fifteen tonnes and may take several years of careful work by our skilled technicians to reveal the bones.

What other research projects are planned for Zuul? Identifying this skeleton as the new species Zuul crurivastator is just the first step in studying this amazing ankylosaur. We’re also planning to study the geology of Zuul’s quarry, so we can pinpoint its exact geologic age and understand what happened after it died. We’re also going to investigate the amazing preservation of Zuul’s skin and osteoderms. If we’re lucky, maybe we’ll be able to find original proteins in the sheaths covering the osteoderms on its tail! Finding dinosaur proteins is rare, but molecular palaeontologists have found keratin (the protein in your fingernails and hair) in dinosaur claws, and collagen (a protein in your skin) in dinosaur leg bones. These soft tissues can reveal important information about the dinosaur’s physiology and relationships.