A Cambrian Puzzle

An ancient, fossilized marine worm crawls into the light.

Published

Categories

Author

A marine worm with a strange crown

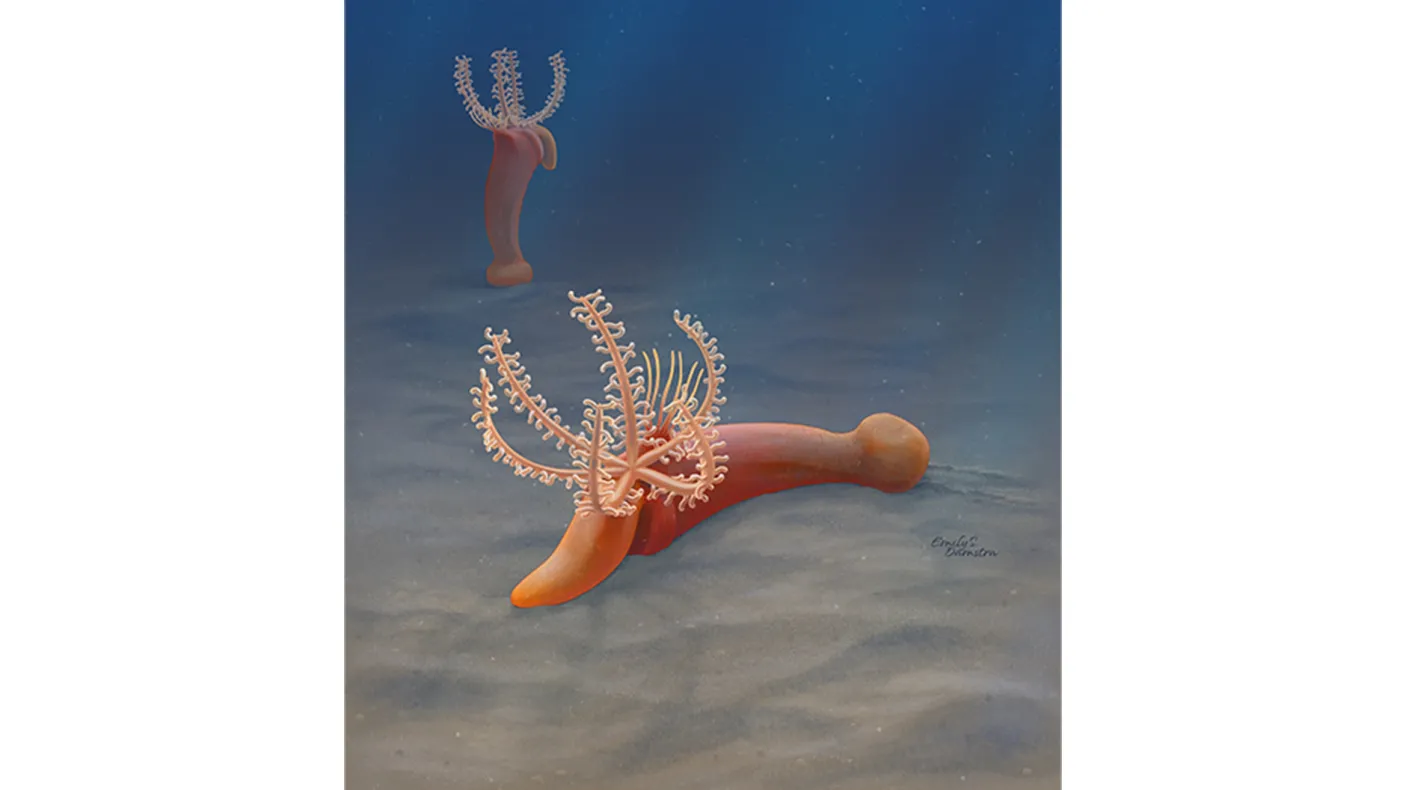

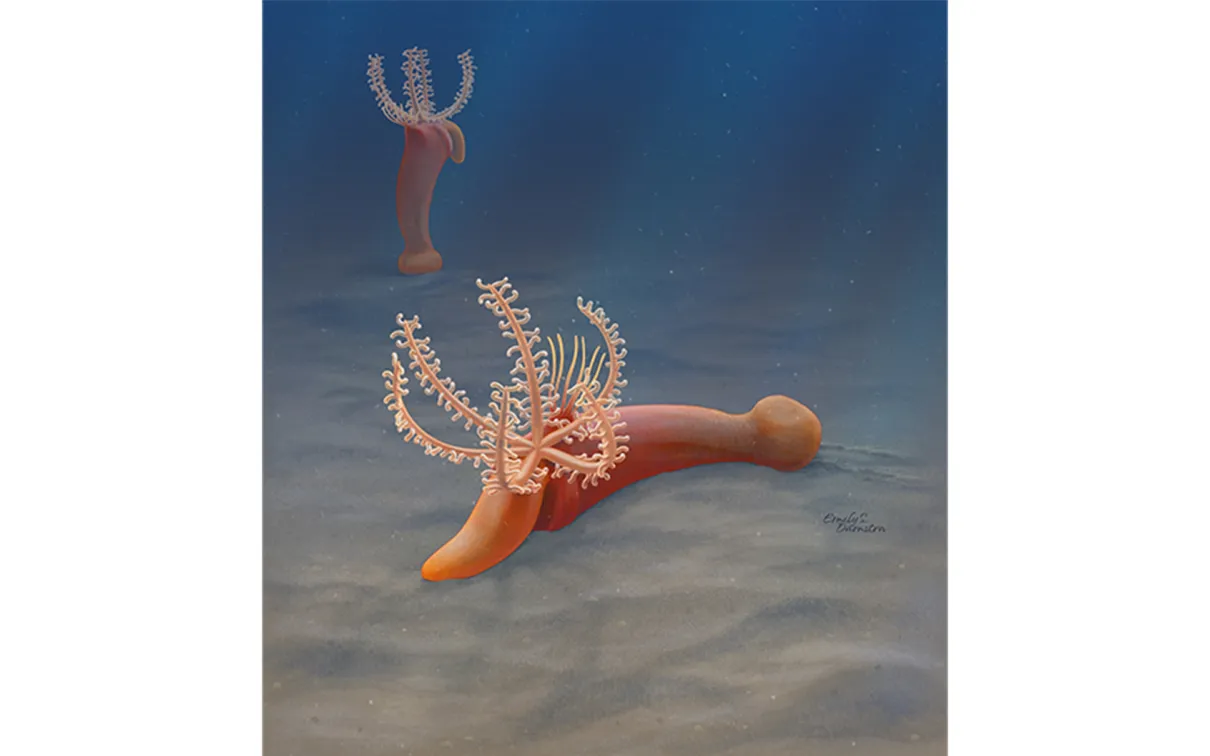

A marine worm with a strange crown of tentacles, published in the journal Current Biology, is the latest new species to be named from the famous, 506-million-year-old Burgess Shale.

Located in the Canadian Rocky Mountains, the Burgess Shale is a site that has remained one of the most important fossil-bearing deposits in the world for over 100 years. One of the key components that make the site so important is the exquisite detail with which it preserves animals. While most fossil sites preserve only the hardest parts like shells and teeth, the animals of the Burgess Shale can exhibit details as minute as feathery limbs, stomachs, and eyes.

This new species, Gyaltsenglossus senis

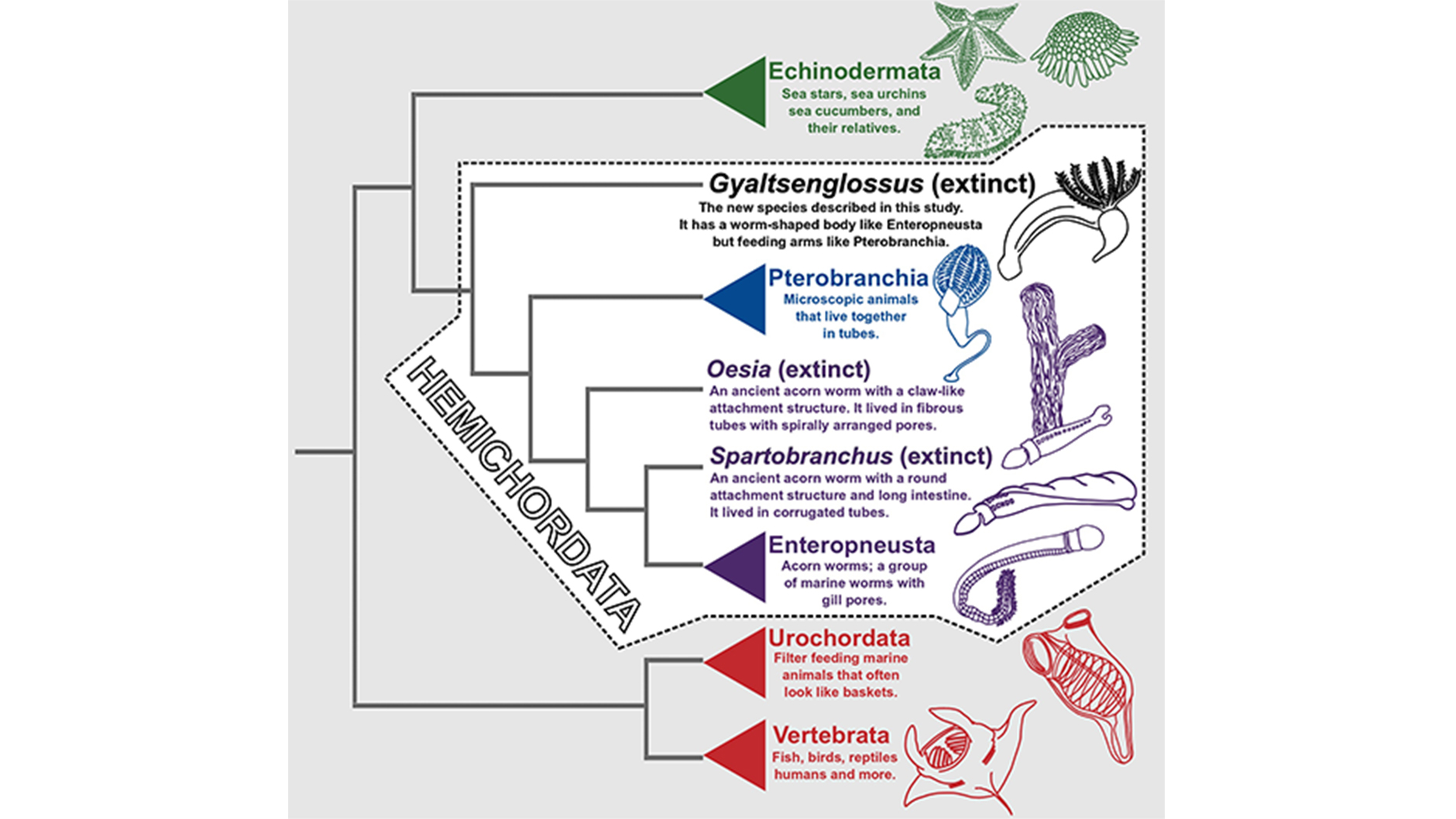

This new species, Gyaltsenglossus senis (pronounced “Gen-zay-gloss-us senis”), is an extraordinarily well preserved animal known as a hemichordate. Despite being only two centimeters in length, it shows fine anatomical structures such as a crown of six feeding arms covered in tentacles. Most importantly, its anatomy is a combination of characteristics found in the two modern groups of hemichordates: the enteropneusts and the pterobranchs. In short, this species helps illuminate the early evolution of this group of animals, a topic which remains a point of major debate among biologists and palaeontologists.

At the heart of this debate is that the two modern hemichordate groups are very dissimilar morphologically and ecologically. Pterobranchs are microscopic animals that feed using tentacles on their arms. On the other hand, enteropneusts (sometimes called acorn worms) are worm-shaped burrowers. Although their relationship is strongly supported by molecular data, few details of their anatomies would suggest any close affinities. This confusion has only been compounded by the poor fossil record of hemichordates. Being almost entirely soft-bodied, they are unlikely to be preserved in most fossil localities; you can count on one hand the number of hemichordate fossil species that preserve the soft tissue anatomy that is critical to understanding their early evolution.

The discovery and description

The discovery and description of Gyaltsenglossus is a major turning point in this debate. Primarly, it suggests that at one point early in their evolutionary history, hemichordates may have possessed features of both the pterobranchs and enteropneusts simultaneously. This suite of characteristics may have allowed early hemichordates some flexibility in their style of feeding: like a pterobranch they could grab food directly from the water, and like an enteropneust they could feed on organic material in marine mud.

Gallery 1

These insights perfectly illustrate

These insights perfectly illustrate the importance of making new fossil finds from places like the Burgess Shale, and this is doubly true of Gyaltsenglossus. All specimens of this new species were discovered in 2010 by a ROM team led by Jean-Bernard Caron (Richard Ivey Curator of Invertebrate Palaeontology) during field explorations from a single isolated block of sedimentary rock; if that one block had been missed during field explorations, this unique new form would forever go undiscovered. Discoveries of this nature are the bedrock of facilitating new observations, which in turn allow us to push our hypotheses about early animal evolution further.

Karma Nanglu

Karma Nanglu is currently a Peter Buck Deep Time Postdoctoral Fellow at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, where he studies the early evolution of the hemichordates and their relatives.

Explore More

Willner Madge Gallery, Dawn of Life Preview

In anticipation of the future Willner Madge Gallery, Dawn of Life, which will be home to the ROM’s world-renowned collection of Burgess Shale specimens, the Museum has a special display of spectacular pieces that will introduce how the new Gallery will present, interpret, and explain fossil life.

Willner Madge Gallery, Dawn of Life

On November 14, 2018, the ROM proudly announced that Toronto philanthropists Jeff Willner and Stacey Madge generously committed $5 million for the future Willner Madge Gallery, Dawn of Life. This investment will establish a new 10,000 square foot permanent gallery that explores the beginnings of life on Earth.

Discover the Burgess Shale in Yoho National Park, which preserves one of the world’s first complex marine ecosystems and is part of the Canadian Rocky Mountain Parks World Heritage Site.