Art, Nature, and the Human Soul

Contemporary artist Elias Sime on staying human in an increasingly technological world.

Published

Category

Author

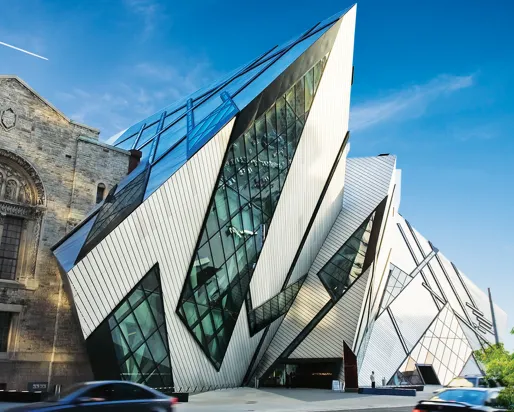

In December 2020

In December 2020, as we were finalizing the design and interpretation of the exhibition Elias Sime: Tightrope, I had a virtual meeting with artist Elias Sime and his curator and long-time collaborator Meskerem Assegued. Elias and Meskerem were at the end of a busy workday focused on the multiple projects and activities at their ever-developing labour of love, the Zoma Museum. Zoma is a beautiful, multifunctional space and garden carved within the bustling urban mosaic of Addis Ababa. The museum opened to the public in 2019.

As with many things in 2020, our digitally mediated conversation felt a bit like a compromise: the best we could do for the time being, but still a welcome and exciting opportunity to connect and talk about Elias’s art and vision.

Gallery 1

SILVIA FORNI

SILVIA FORNI: Elias, you were trained in a very traditional way in art school. What inspired you to work with materials that are very unique and somewhat unconventional?

ELIAS SIME: This is a hard question, and I sometimes wonder how to answer it. I don’t think of academic learning as something that makes one an artist. Producing art makes you an artist. In my experience, art comes from a natural inclination. You have to be born an artist.

Education can teach you technique and mechanics. That in itself is a good thing, but education alone doesn’t make you an artist. And you see this in other fields, not just art. I think whenever you follow your natural inclination, you can do something good.

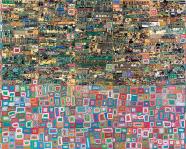

FORNI: Elias Sime: Tightrope contains two bodies of work: your earlier pieces, in which you were using thread, buttons, and bottle caps, and the Tightrope series, in which you introduce different types of materials and techniques. What do you look for when selecting the material for your art?

SIME: Whichever material I select, I think of it as something that has been touched by people. For instance, fabrics or threads have a kind of attachment to somebody. Bottle caps were made by machines, but there are people who used those machines.

I have very much that same kind of feeling with the Tightrope material. There’s more connectivity even, because the electronic materials aren’t touched by people in a tactile sense alone. They’re attached to the personalities of the people using these devices, an extension of self even. They have transformed—from objects that have been touched to materials that have entered our souls, become part of who we are.

All the elements I use—whether it is bottle caps or buttons, early materials or what I use now—they all have stories. Each material is like a novel, and what moves me is the stories it tells.

In our fast-developing technological world, the wires are our veins, our blood vessels. They are what connects us.

FORNI: Tightrope

FORNI: Tightrope is a title that you created for this series. What does “tightrope” mean for you?

SIME: The title was born out of many conversations with Meskerem. When I started creating this work, the two of us had several discussions about the stories we want to tell through this art. It was Meskerem who came up with the title.

There’s an Ethiopian story about a rope that snaps after it has been pulled too hard. Anything that’s tensed will break when more pressure is put on it. Then, there’s the uncertainty of walking on a tightrope, of always having to figure out how to keep one’s balance.

When we were discussing the title, we thought “tightrope” would be a good reflection of the contemporary context, which is what my work is about. I always talk to Meskerem when choosing a title and a lot of thought goes into it, because once the title is out, it’s out; there’s no way to take it back. It has to really be something that reflects what the art is and, at the same time, needs to inspire. Titles cannot be rushed.

FORNI: What is this tension? Is the rope breaking or are we struggling?

SIME: It is both. The work that I’m doing presently is deeply connected to what I feel right now. I am using electrical wires. In our fast-developing technological world, the wires are our veins, our blood vessels. They are what connects us.

Sometimes, I feel like technology gives us knowledge while not giving knowledge at all. There are things that you purposely do using this technology, and then, there are times when you do something because you don’t know, when you’re not aware. On one hand, it’s dangerous, and on the other, it actually helps.

But what we’re missing in life, because of the intensity of the technology, is the human soul. It’s part of the feelings we have when we see one another, eye to eye. Or the movement in our faces, our facial structure, our mouths, our noses, all our movements and the way we touch each other. All these things are missing when technology interferes. Technology takes away that human soul.

Right now, I’m looking at you and you’re looking at me, but we’re very far apart. I see your eyes through the screen, but having a real connection is not easy. But the actual feeling that you have, even if you’re angry, I don’t see it. I only see part of you. That’s what we miss when we’re not meeting in person. Yet, at the same time, I also understand the importance of technology.

I think about what happens in the future. I think about our passing away, once we’re no longer alive, into the very far future. And I wonder, what will happen to families, to love, to people being in touch? How will technology affect our relationships long into the future? Maybe I’m being a little harsh, but I sometimes worry that we are becoming robots.

What we’re missing in life, because of the intensity of the technology, is the human soul.

FORNI: Besides the element of human connections

FORNI: Besides the element of human connections, your work also considers the human relationship with nature. What is the importance of nature in your work?

SIME: Nowadays, the computer motherboards that I am finding are mostly painted green, and finding different colours is not easy. Green is the most dominant colour now. I sometimes think about the people who create this machinery, the people who decide which colour they will use. I wonder if they pick the colour because they understand they’re missing greenery. Because now, almost everything that I touch on the boards is green.

Another thing I think about is the origin of these materials. Where did they come from? What’s the source of these materials? At the end of the day, they all come from the ground. All the metal pieces you see behind this machine, all the wires, the plastic wires, they’re all dug out, they’re part of that whole product. You need to dig through the earth to find these materials. In one way or another, all the computer components are a product of nature, even if they look disconnected from humanity.

The materials themselves are products of the earth and nature. In my work, they become colour.

I play with the colours. There’s a deep green, light green, these various types of green that I put together to make a composition tell the story that I feel needs to be exposed through the work. There are times when I just can’t find that one colour I’m looking for. Sometimes I’m looking for a certain kind of red, and it’s not there, or another colour that is not there. So I wait for them. I wait as long as it takes to get those colours. It’s the colours and the way I assemble them together that makes the composition. It is how I tell the stories that I want to express.

FORNI: We live in a very different world now

FORNI: We live in a very different world now from when we met in person. The world has changed a lot. I was thinking, as I was working through this exhibition, how the pandemic has brought into focus the idea of connectivity, which is at the core of your work. Has your present work been influenced by what has happened in the last year?

SIME: Yes, the pandemic has actually brought the world together. It forced us to think about humanity. The virus doesn’t select colour. It doesn’t choose poor or rich. It doesn’t care about ethnicity or anything. It just attacks you because you are human. And it has forced us to ask questions: What is love? What is humanity? All these questions that we had put aside are now on the table.

My recent work plays with the idea of the dome. I installed a piece in Amsterdam that is a dome cut in half once and then again. So there are four parts and then eight parts if you keep cutting it. That work reflects the situation that you’re talking about. It holds you because it’s a dome-like structure—a concave. But it also talks about globalization as a whole piece cut into so many pieces.

The sculpture that I’m creating right now also deals with globalization because it actually talks about the need for unity, the need for us coming together despite our differences. When you split it up, those are our differences. But when you put it together, it creates a dome, the whole sphere. My work is directly related to what is happening today.

Actually, as you were asking me this question, what came in my mind was something Meskerem used to tell me: her wish about having an exhibition where the work is not identified by the name of the artist that made it.

What would happen if the work was exhibited with no information about the artist? How would it be if people were able to see art without filtering it through their idea of the person who made it? It makes me emotional because that’s the world we want to be in. Where you are and who you are, not because of where you’re born or where you come from. Because this is what COVID is doing. It’s teaching us to be human. Even if it passes, it has left this lesson for us. Everything is human, no colours.

Gallery 2

FORNI: My next question is for both of you

FORNI: My next question is for both of you. What connection do you see between the artwork that Elias creates to be exhibited and what you are making together in Addis through Zoma? How do these two elements of your creativity connect?

SIME: When Zoma was created, it was a collaboration, and that was a must. Collaboration is very important, but it does not work by itself. Collaboration has to be harmonious; it can’t be forced. It has to have an agreement from both sides. Zoma was our creation. It is a beginning of two people’s ideas, but it’s not the end of the idea. You have to think of it as something that’s in a global context. So Zoma is no longer Meskerem’s place, or Elias’s place, or Elias and Meskerem’s. Zoma has become Zoma while we’ve become the background.

What you need to think about when you think about collaboration is you can’t clap with one hand to make noise, but when you use two hands to clap, you actually start making noise. The noise gets louder, and you get heard.

The symbolism of the two hands is also effective. When you think of two leaders meeting, they shake hands. All the rest of their bodies are still, but the two hands are shaking. That’s unity.

So whenever we shake hands, there’s a symbol of unity. The only difference is understanding the handshake that united us.

Zoma is a collaboration, and my art is also a product of collaboration. The research, where the material comes, all the people who collect for me or who assist me are collaborating with me. And that extends to the people who come to see the work and comment on it. Even what we’re doing right now is a collaboration.

MESKEREM ASSEGUED: I believe that we are products of our dreams. We are part of a remarkably diverse natural world. We exist because we share and collaborate with all the different elements of nature. Think about the amount of abuse the Earth has endured time and time again. Yet it continues to feed us because it too must exist. The oxygen we breathe in comes from plants, and the carbon dioxide we breathe out is food to the plants that we eat. This is a positive collaboration that our life depends on. When we are negative, we are destructive to ourselves and to others. The destruction of the Amazon rainforest affects each one of us regardless of differences. If we dream about a fair, loving, and prosperous future, we will achieve it because everything we do will focus on it. Elias and I have been working together for many years. We collaborate on almost everything. At the same time, we also respect our differences. We both believe that great outcomes are products of collaboration and positive outlook.

FORNI: Elias, you have a deep sense of optimism

FORNI: Elias, you have a deep sense of optimism. How do you maintain this in face of the tensions of the present moment?

SIME: Being pessimistic, thinking negatively, finding something to oppose is easy. Even if I want to skip talking about the situation in Ethiopia now, I still want to talk about humanity in general. Negativity creates more negativity.

I believe that, for the sake of humanity, we should build life from what is positive. What are the positive things that come out of even the hardest situation? What are the good parts of a story?

Think about this. When you wake up feeling like it’s going to be a good day, you’ve decided that promising things are going to happen. So you start being curious. Great things are possible because that’s what you’ve told your mind, and that’s what it accepts.

But when you wake up feeling sad, that emotion will follow you. So compare the two feelings and make a choice. How do you want to lead your life? Even when you get sick, when you’re in the worst situation, if you can force yourself to think of the situation’s positive aspects, you can start trying to find them. Then, things start changing for the better. That’s how I want to think.

Thinking this way isn’t easy, because that’s not what we’re used to. But I also believe that we’re born positive.

Silvia Forni

Silvia Forni is Senior Curator of Global Africa at ROM.