“Charming, remarkably wild, and humorous”: Yayoi Kusama’s Iconic Pumpkins

From prints to sculptures, Kusama’s pumpkin are a reflection of the self.

Published

Category

The pumpkin is an iconic symbol of Halloween

The pumpkin is an iconic symbol of Halloween, and carved jack-o'-lanterns are a familiar face of the season. Irish legend places the jack-o’-lantern in an in-between space of life and death, where the lantern is the sole source of light for Stingy Jack, who was doomed to roam the earth even after his death. Whether it is fairytale folklore or pumpkin spice lattes, this innocuous and ambivalent winter squash has become a mainstay in our food and culture.

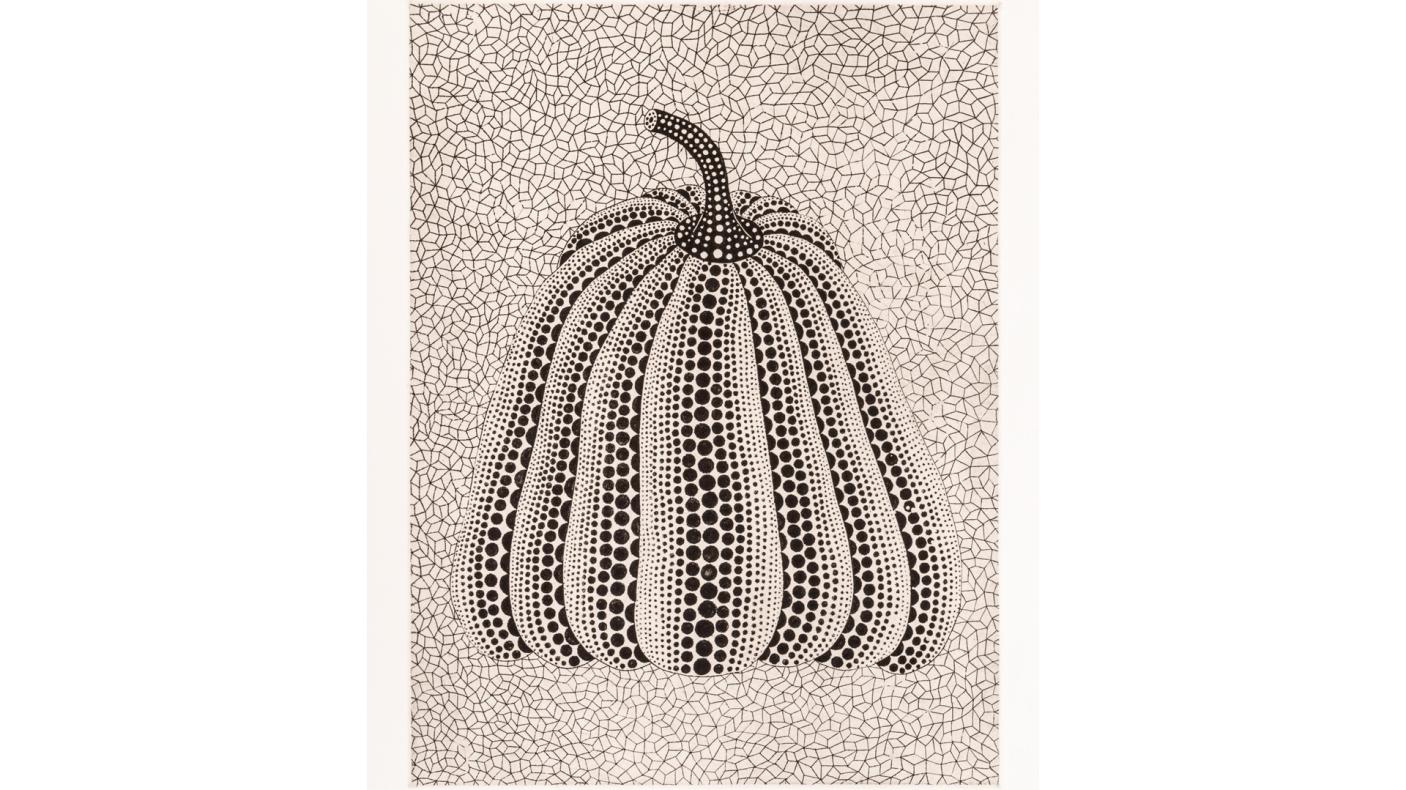

Pumpkins (kabocha in Japanese) in the works of Yayoi Kusama, a 92-year-old Japanese avant-garde artist, too, embody this ambivalence—adorable and eerie, delightful and uneasy at the same time.

Kabocha, a rather unpretentious, rustic vegetable, has been a favourite motif for Kusama since the 1950s, when she was an art student in Kyoto. “[They are] charming, remarkably wild, and humourous,” says Kusama, explaining her special love for pumpkins. She uses the motif of kabocha covered with polka dots in both 2-D paintings and prints and 3-D sculptures.

More renowned today are the irregularly shaped pumpkin sculptures of various sizes and colours, which are relatively recent works of hers since the 1990s and can be found in museums and public spaces around the world. Her iconic immersive installation work with multiple mirrors and objects, Mirror Rooms, too, often feature dotted pumpkin sculptures. The visitor-engaging nature of Mirror Rooms have catapulted her name beyond art lovers and onto hundreds and thousands of social media accounts across the world.

While Kusama was originally trained

While Kusama was originally trained as a painter in Japan, when she lived in New York City between 1958 and 1973, she tirelessly produced wide-ranging works of painting, sculpture, film installation, performance art, or fashion, holding a vital space in the city’s avant-garde art scene. There, she first became known for her Infinity Net series of paintings, or large canvases filled with monochromatic, repetitive “net” patterns. The three essential elements of her distinctive style—accumulation, repetition, and obsession—evolved from here.

Since 1979, six years after returning to Japan, Kusama has added prints to her main media, of which ROM’s example is one. It coincided with the time when she also began using more representational motifs such as pumpkins, flowers, or butterflies in vivid colours. While in different forms and colours, her printed kabocha look as if they are all alive and wriggling. The motif’s living energy seems to come not only from their irregular forms, but also from their dotted surface and the net-patterned background.

Both dots and nets represent the hallucinatory images that Kusama has been suffering due to mental illness since her childhood. By accumulating the obsessive repetition of dots or nets (or other such motifs), she expresses her mental world in a condensed form, and in doing so, explores the ways to fulfil her earnest desire for the salvation of self from suffering and anxiety.

According to Kusama, the dots are her self. They reflect her disposition for eternal self-obliteration—or death and reincarnation—understood as the return to the universe. She writes in Kusama Yayoi—Soul Burning Flashes, the exhibition catalogue to her solo show in Japan in 1998, “my soul returns forever to the universe, via transmigration, as one of the interminable polka dots.” Hidden behind the apparently light-hearted motifs used by Kusama is a deep and dark side of her art.

Our simultaneously cute and eerie dotted kabocha simultaneously juxtaposes comfort and anxiety, cell and universe, or simplicity and complexity. Ultimately, it invites us to the in-between world of life and death, much like the jack-o'-lantern does.

Akiko Takesue

Akiko Takesue is the Bishop White Committee Associate Curator of Japanese Art & Culture at ROM.