Fin-tastic Beasts of the Great Lakes

We have quite a bit to “carp” on when it comes to aquatic invasive species.

Published

Categories

Author

Grab your snorkelling gear

Grab your snorkelling gear because we are going underwater with ROM’s Ichthyology (Fishes) team! ROM and university scientists, along with other groups such as the Department of Fisheries and Oceans and conservation authorities, are out on the lakes each summer monitoring trends in fish populations. Turns out, humans are not the only ones travelling far distances to visit the Great Lakes. Non-native species are frequently found in these surveys.

Non-native fishes are species that have been introduced to a habitat outside of their natural range. Some are introduced accidentally, such as round gobies, believed to have arrived in the Great Lakes through ballast water. Others have been introduced purposefully. Non-native species typically have a bad reputation. While it is true that not all non-native species cause harm, some do bring economic, environmental, or even physical damage to humans. These are considered invasive species. Among other issues, these introductions impact the biological integrity of aquatic habitats, which harms the fisheries, outdoor recreation, and tourism industries.

The sea lamprey is an infamous example of an aquatic invasive species (AIS) in the Great Lakes. Sea lamprey is native to the Atlantic Ocean. Outside of their native habitat, they threaten native fishes as they latch onto, and feed on, their hosts.

Another example of an aquatic invasive species is the goldfish. Goldfish, native to Asia, is a favourite family pet here in North America. If they find their way to a North American watershed via illegal release of aquarium pets, they disrupt aquatic food chains as they feed on eggs, algae, and small invertebrates. Moreover, their feeding stirs up vegetation, increasing turbidity and lowering oxygen levels.

Gallery 1

One of the best ways to combat AIS

One of the best ways to combat AIS is to prevent their establishment, because once they have invaded, control comes at a steep price. Some potentially invading AIS in the Great Lakes include carp from the family Xenocyprididae, including the grass carp, silver carp, bighead carp, and black carp.

Grass carp were introduced into the United States in efforts to control plant growth in aquaculture ponds. Due to flooding, they escaped these ponds and made their way into the Mississippi River, allowing them to broaden their distribution northwards. Grass carp are a prominent threat to the Great Lakes ecosystem as they have already been found in several parts of Lakes Ontario, Erie, and Huron.

Young grass carp can eat nearly half their body weight each day

Young grass carp can eat nearly half their body weight each day in aquatic vegetation. While that may sound like a healthy diet, it is anything but healthy for our wetlands. Young grass carp only digest about 40 percent of the food they consume each day, while the rest is added back into the water in the form of waste. Similar to Goldfish, this increases turbidity of waters and lowers the oxygen levels. What was once crystal-clear oxygenated water becomes algal-filled murky water, thereby creating a hostile environment for most native fishes.

Silver carp cause harm not just to aquatic ecosystems but also to people. Leaping several metres from the water in a frenzy, silver carp have been known to damage boats and boaters alike.

Like the grass carp, silver carp have extreme feeding habits

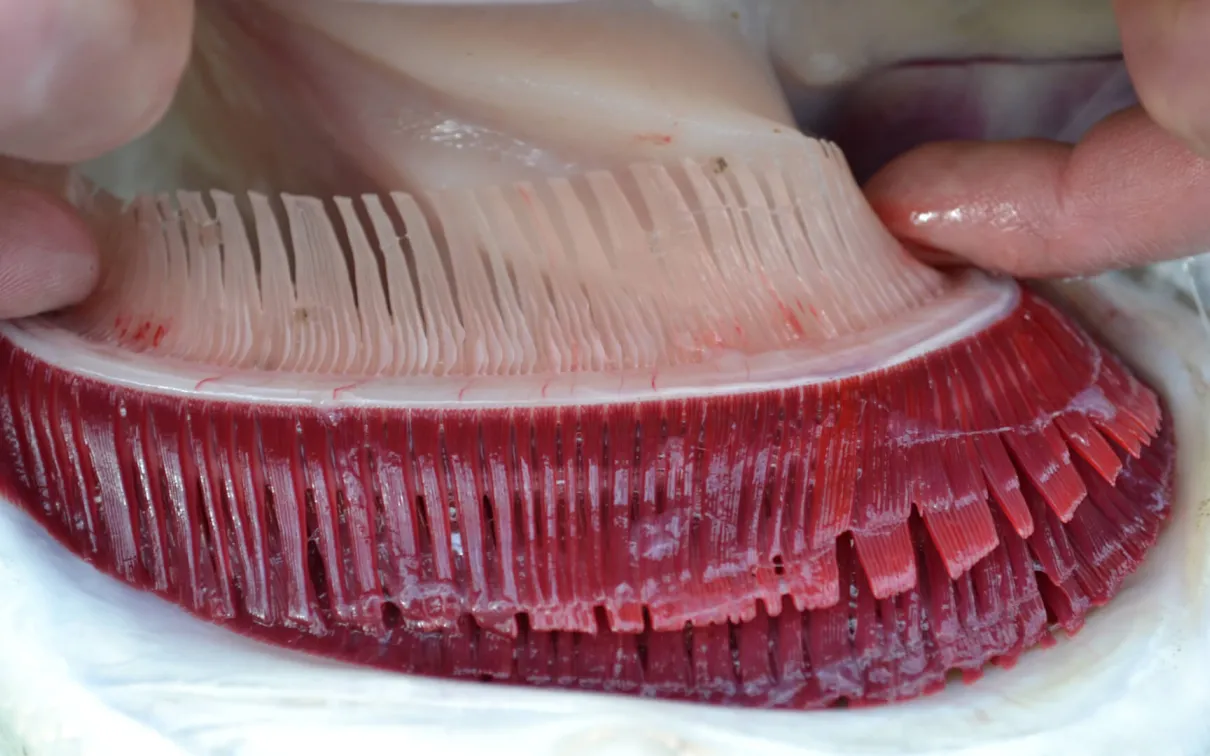

Like the grass carp, silver carp have extreme feeding habits. Silver carp are able to strain plankton—a vital food source for native juvenile fishes, using specialized gill rakers with spongy pads that trap prey. Keeping them out of our waters is critical, not only to protect native species, but also to protect anglers and recreational boaters from their acrobatic tendencies.

Gallery 2

Bighead carp look similar to silver carp

Bighead carp look similar to silver carp, some referring to these species as looking like “upside-down” fish. Bighead carp, like the silver carp, also boast a specialized filtering system. Using specialized gill rakers, they feed continuously, as they have no “true” stomach—talk about an all-you-can-eat buffet.

Black carp have been found to grow up to 6 feet in length. They have molar-like, large teeth in their throat called pharyngeal teeth, a structure that allows them to crunch hard-shelled organisms like native freshwater mussels. Black carp threaten native fishes, mussels, turtles, birds, and even some mammals like raccoons and otters.

The more eyes we have on the water, remaining vigilant against these non-native species, the better. So if you are out fishing, make sure you know how to tell native species from non-native, and do your best to prevent the spread of species beyond their natural range. You can learn to recognize native and non-native fishes by exploring the pictorial keys, comparative photos, and brief descriptions in the recently published A Field Guide to Freshwater Fishes of Ontario. The new edition includes current information on 129 Ontario native fishes, along with 21 introduced and established populations of non-native fishes.

Get your copy of ROM's newest field guide

A Field Guide to Freshwater Fishes of Ontario is the definitive guide to Ontario freshwater fishes. A beautiful and accessible full-colour field guide to all species of freshwater fish found in Ontario, this sold-out book was revised and has been republished as a new edition, with more than 600 photographs. The book features new and revised species accounts, more than 150 new photographs and illustrations, as well as updated names, identification keys, range maps, and conservation statuses.