Migration Through the Lens of an Unknown Burmese Studio

A collection of images captures the visible migrant Indian community along with the social isolation caused by British temporary migration policies.

Published

Category

Author

This image is part of a series of 99

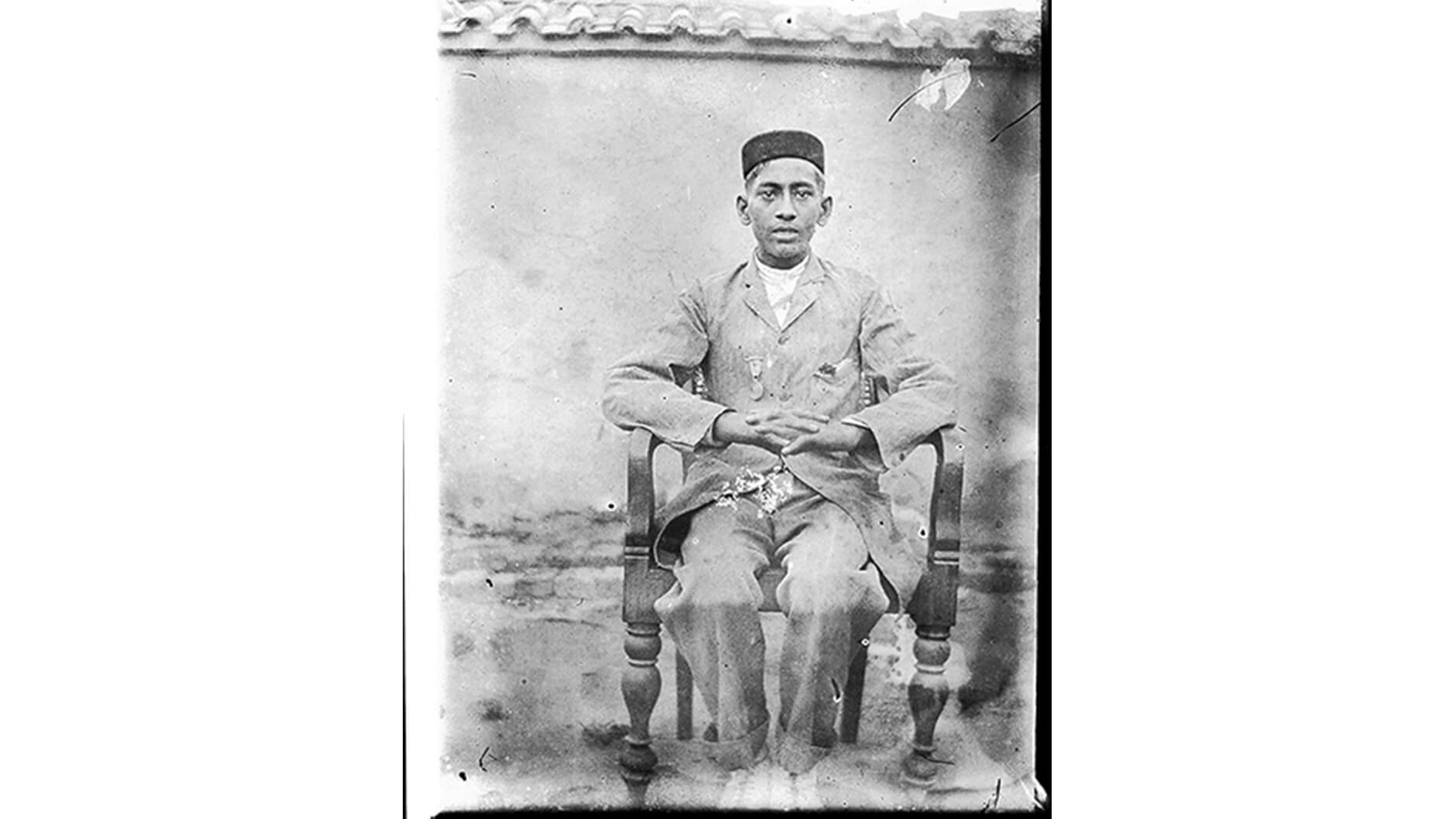

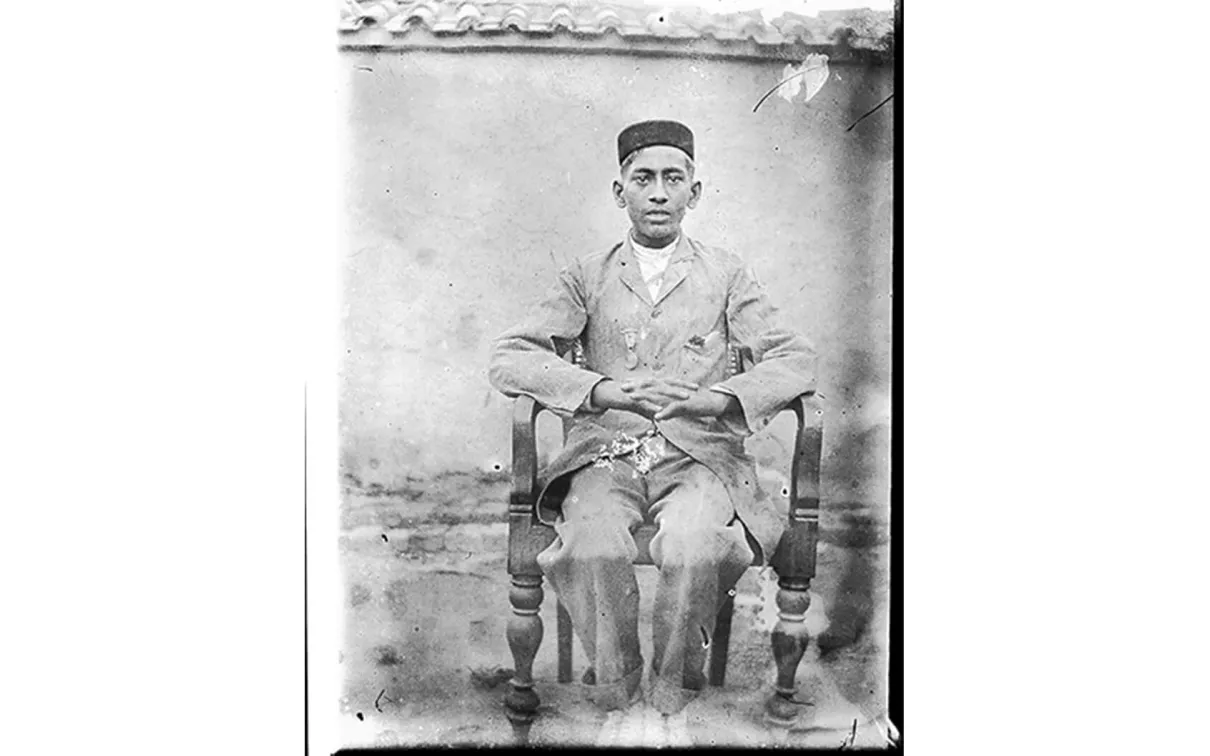

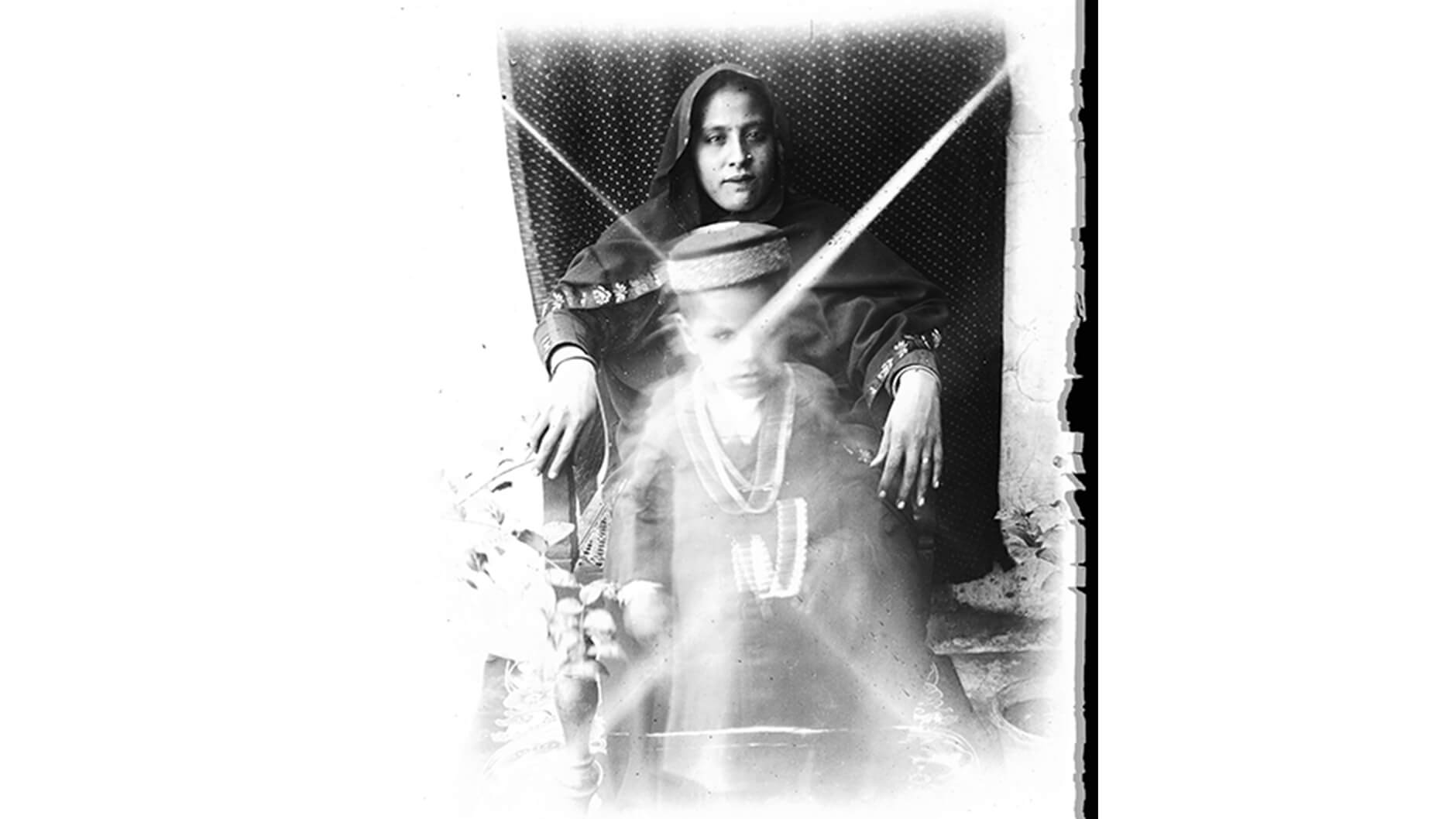

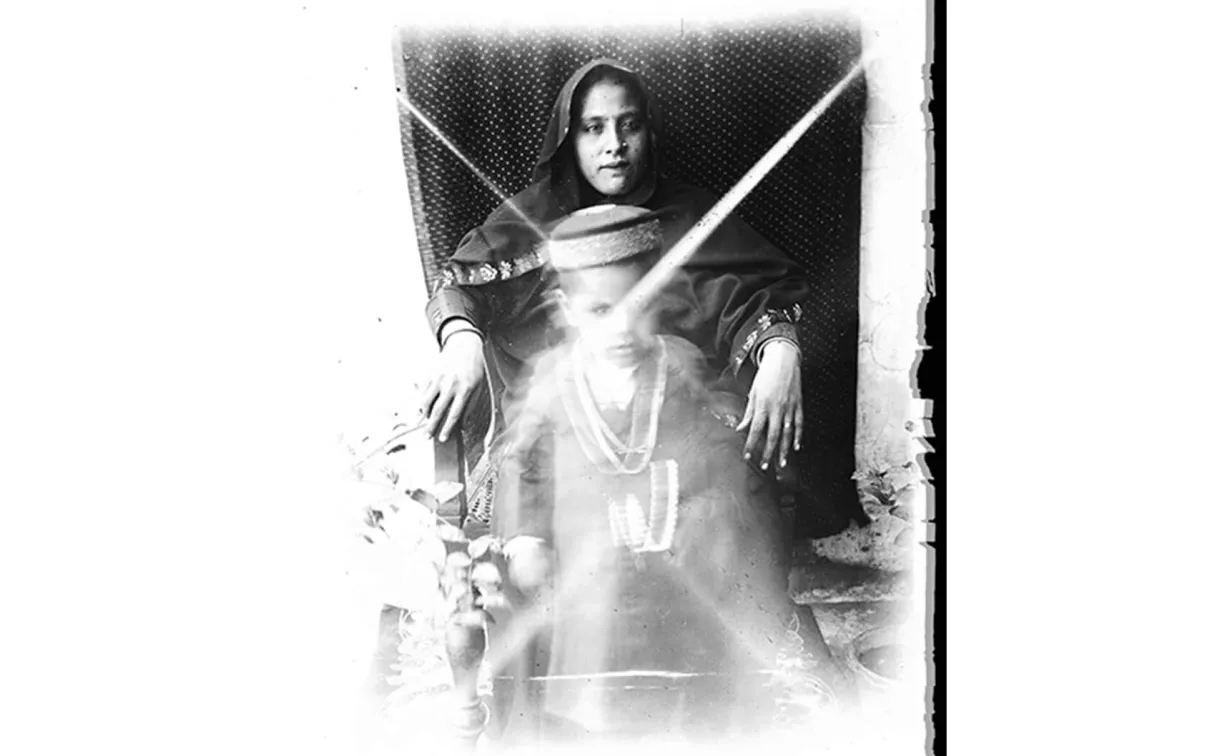

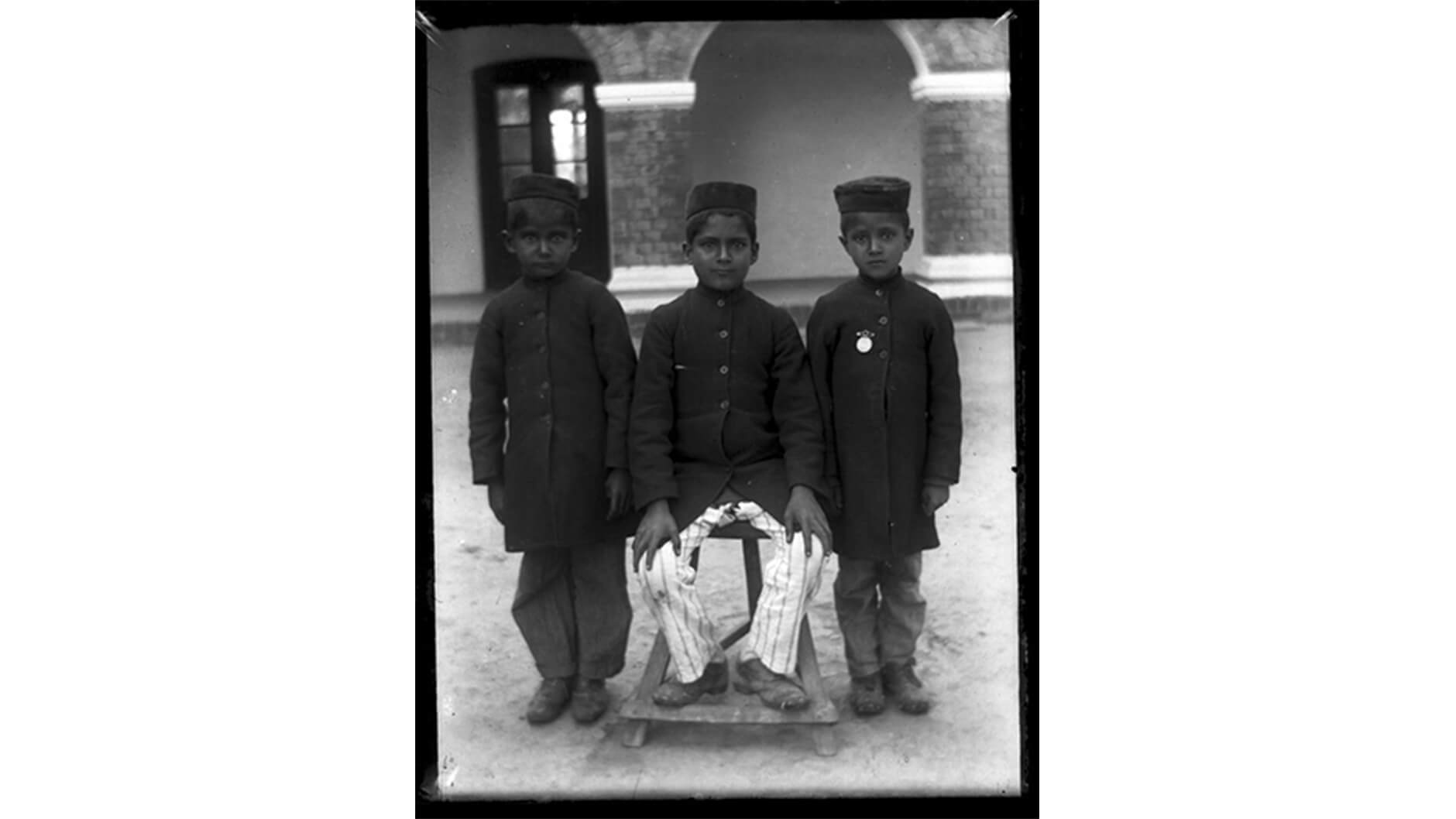

This image is part of a series of 99 negatives from an unknown commercial photography studio in Mandalay, Burma (Myanmar). Mostly dated to 1890–1910, they are largely studio portraits of Indian and Burmese men, women, and children as individuals, couples, or groups. Showing diverse social, cultural, and socio-economic backgrounds, some images are taken in a photographic studio with props and painted backdrops, while others are taken outside against walls or simple fabric backdrops. Some images show the streets of Mandalay in which graves, store fronts, horse drawn carriages, and railway cars are visible.

Interestingly, over half of this collection represents negatives that were most likely never printed due to overexposure and blurriness, reflecting attempts at early photography that went wrong.

Normally, these ruined negatives would have been discarded or sold and reused for their raw materials, making this intact collection rare and quite interesting. Several of those that were fit to be reprinted show indications that the negative plates were hand painted on the hands and/or faces to lighten and smooth the appearance of the sitter’s skin.

This collection is unique in that it preserves a body of work (rather than only single surviving images) by an unknown Burmese photography studio. It also makes visible the migrant Indian community and the ways in which they occupied a hybrid cultural space in colonial Mandalay.

Gallery 1

Britain began its colonization of Burma

Britain began its colonization of Burma in 1824 and, by 1885, had also colonized Upper Burma, which encompassed Mandalay where this photo was taken. Burma joined the larger British Empire being administratively and politically governed as part of colonial India.

Thus, the British controlled Burma’s commercial sphere, bringing in migrants from its other colonies, especially India. As noted by Amarjit Kaur in her paper “Indian Labour, Labour Standards, and Workers’ Health in Burma and Malaya, 1900-1940,” by the 1860s, Burma’s rice export had exploded, bringing in immense profits due to rice supply disruptions during the American Civil War, steam powered shipping and the opening of the Suez Canal. Transport was easier and cheaper than it had ever been. All these factors necessitated migrant labour to keep up with the increased rice production. Due to India’s close proximity, Indian migrants from factories, urban centers, and ports were recruited to fill the labour shortage.

The British manipulated migration policies to ensure that Indian migration was often temporary with geographic and social isolation in their places of work exasperated by linguistic, cultural and religious differences between Indian migrants and the local Burmese population.

Kaur argues that these factors almost completely ensured that assimilation and/or acceptance of Indian migrants by the native Burmese was highly unlikely and that it allowed low wages and racial disparities in the workplace to go virtually unchecked. As such, Indian migrants in the 19th century rarely settled permanently in Burma. Additionally, the ratio of women also able to immigrate was prescribed at 25 women to 100 men in 1864, meaning that it was difficult for many to start families. It was only by the 1930s that the ratio was allowed to increase along with wages, allowing for more permanent settlement.

Deepali Dewan

Deepali Dewan is Dan Mishra Curator of South Asian Art & Culture, Royal Ontario Museum.

Justine Lyn is a former ROM intern, an undergraduate student in the Historical Studies Department, University of Toronto Mississauga.