Up Close with Five Japanese Warrior Prints

A short history of the representation of warriors in Japan.

Published

Category

Author

In 2009, the late McMaster University professor James King

In 2009, the late McMaster University professor James King donated 136 Japanese musha-e (warrior prints) to ROM, adding to the Museum’s already formidable collection of Japanese prints. As King and co-author Yuriko Iwakiri note in their book Japanese Warrior Prints 1646-1905, these musha-e, which span from the seventeenth to the early twentieth century, were mostly inspired from folklore and historical battles between the 10th and 14th century.

Here are five of those prints—and what they can teach us about Japanese history.

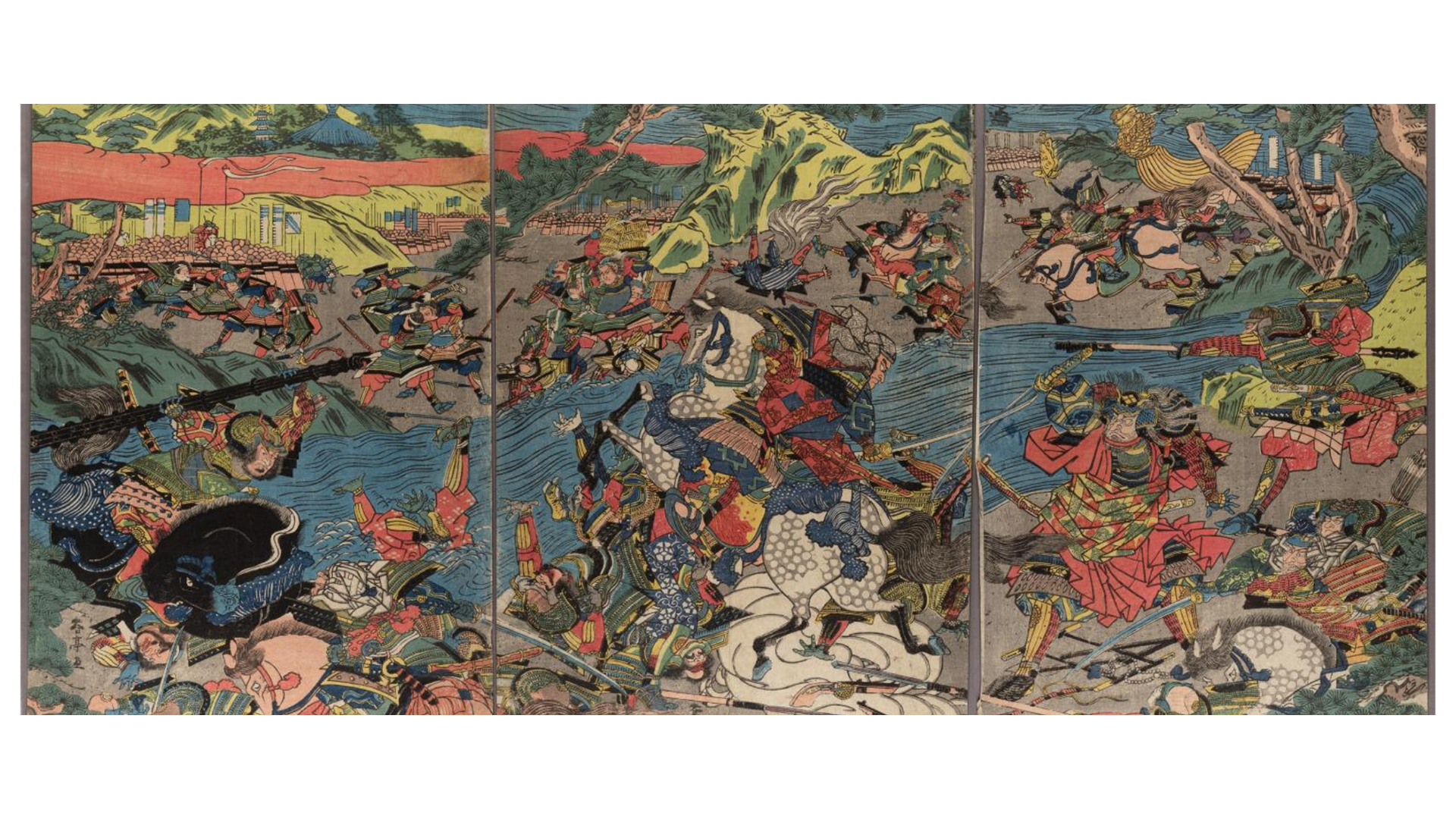

Warriors in Battle

In this triptych by Katsukawa Shuntei, we see hundreds of warriors in motion in a battle between two powerful generals, Takeda Shingen of Kai Province and Uesugi Kenshin of Echigo Province, in 1561. One interesting detail is the use of firearms, which can be found at the bottom of the centre sheet. This lets us know the battle depicted occurred after Portuguese firearms were brought over in 1543 and how Japan began to incorporate firearms into their weaponry.

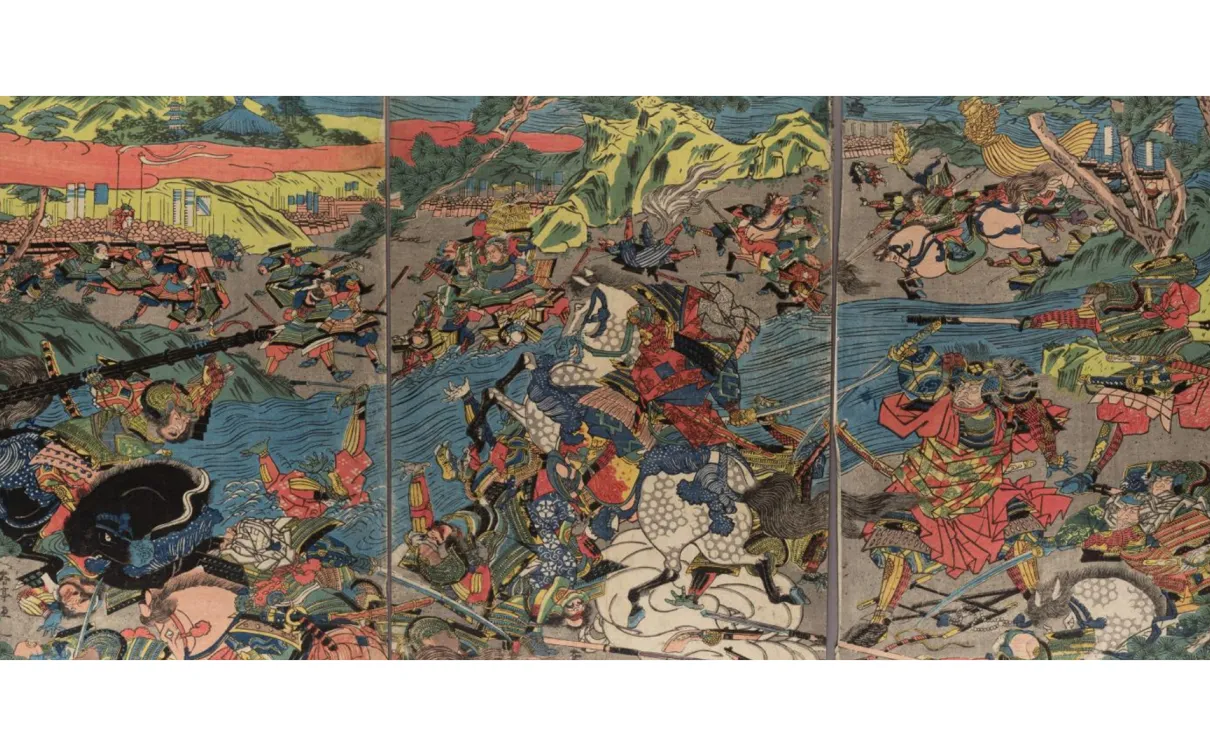

At 126 centimetres in length

At 126 centimetres in length, this unique woodblock print by Utagawa Kunisada is the largest print in the King collection. It depicts a great 12th-century battle between the Minamoto and the Taira families, who were in constant dispute at the end of the Heian period. The Minamoto can be seen arriving from the sea to defeat the Taira family, the leading power at the time. The Minamoto actually won this battle and founded the first warrior government in the Kamakura period, but Kunisada focuses more on the conflict than its result.

Musha-e through Theatrical Performances

A common genre of musha-e are kabuki, or Nō actors, playing out historical battles between warriors, as these plays were popular in Edo culture. Just like a modern-day advertisement, prints of actors were issued to publicize a play. As King and Iwakiri note in their book, fans of these actors could also collect these prints, establishing a dedicated following for theatre actors.

Utagawa Kuniyoshi’s 1862 print above shows two famous actors, Sawamura Tanosuke III and Bandō Hikosaburō V, reenacting a famous encounter between Minamoto Yoshitsune and Benkei on a bridge in the 12th century. The two characters would easily be recognized, as Kuniyoshi exaggerated their iconic features. Benkei was a warrior monk known for always carrying seven different weapons and Yoshitsune was a young samurai, who is shown here as short and youthful.

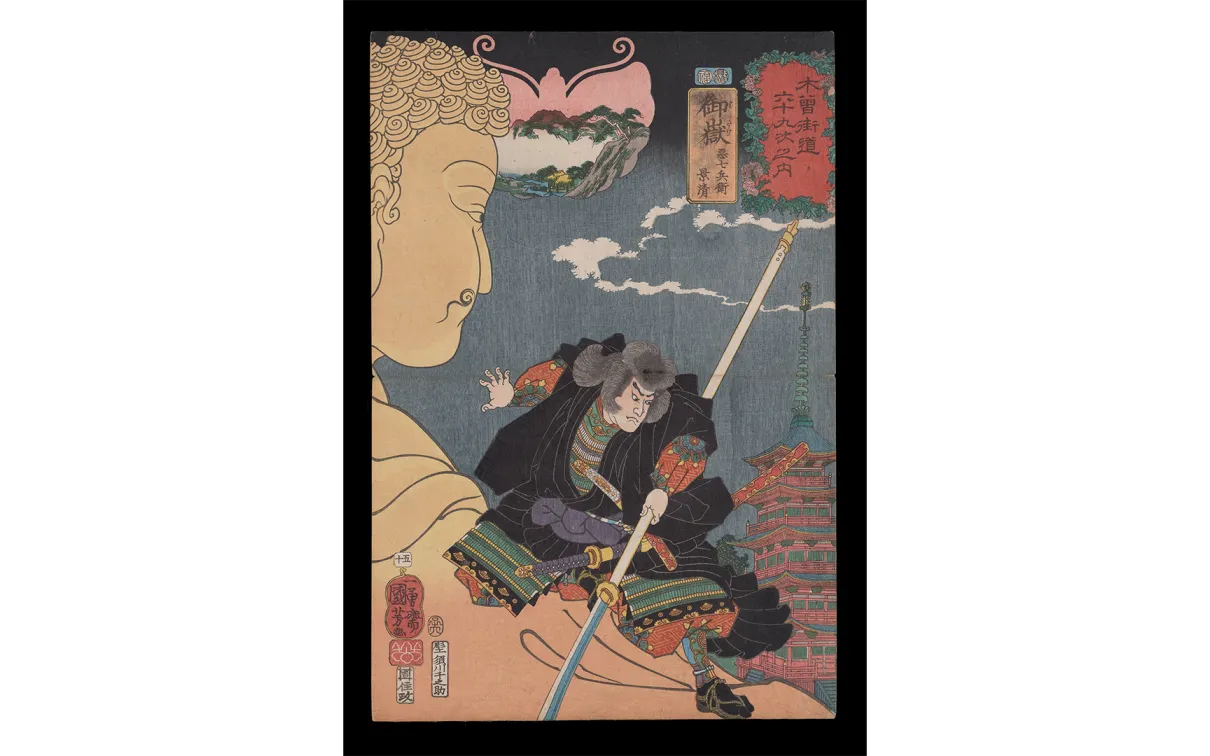

The subject of this print

The subject of this print, also by Kuniyoshi, comes from a Nō play called Daibutsu kuyō. It depicts an actor playing Taira no Kagekiyo, who is trying to flee from his enemy by jumping on top of the giant Buddha at the Tōdai-ji temple in Nara. Like many musha-e, this print dramatizes Kagekiyo’s story, revealing how artists in the mid-19th century altered history to glorify warriors.

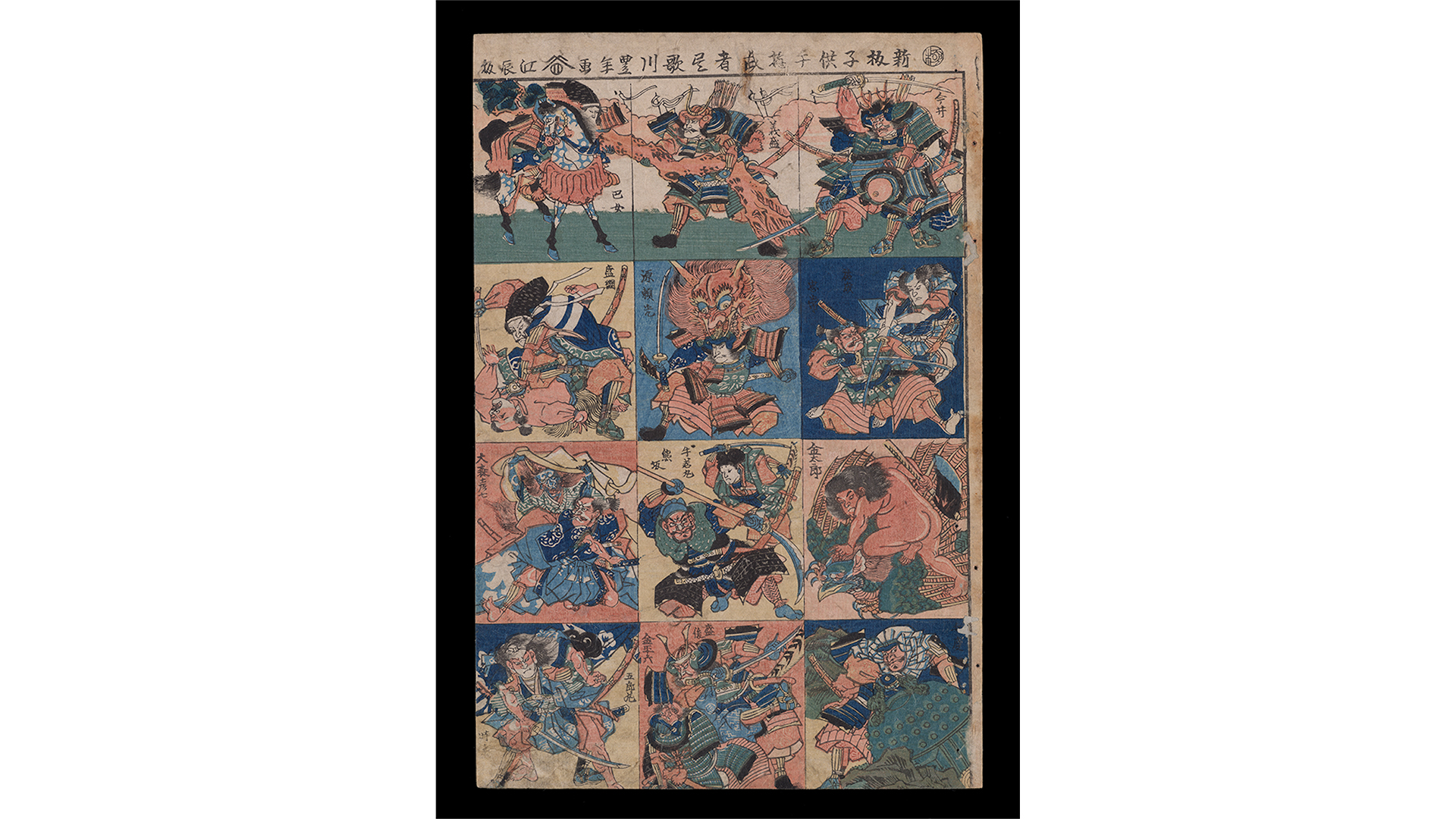

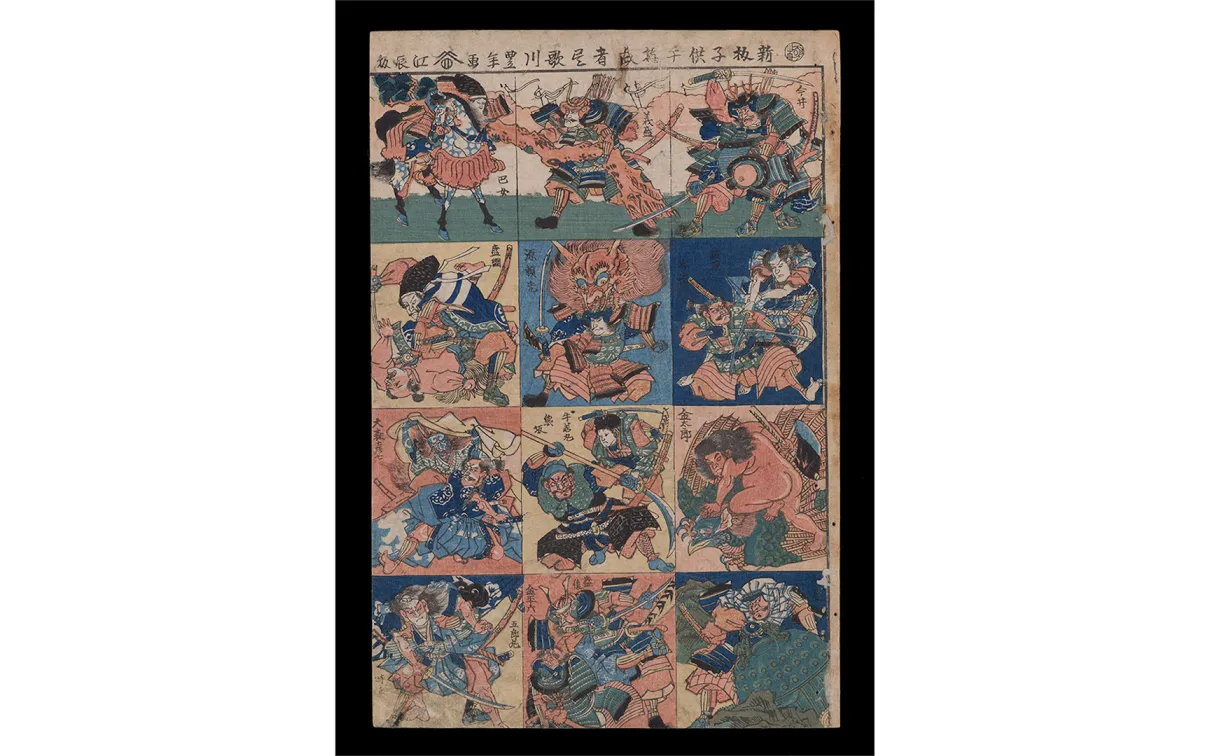

Warriors for Children

Omocha-e, translated to toy-picture, is a sub-category of musha-e made specifically for children. Omocha-e contained smaller images of characters children could cut out, play with, and paste into collection albums, almost like today's trading cards. This omocha-e—which, given its intended use, is in remarkable condition—is made up of iconic images of heroes and mythical monsters from Japanese folklore and history.

Kintaro, a child said to be born with superhuman powers, is on the right square of the third register. According to folklore, Kintaro was raised by a mountain witch and grew up to fight and capture monsters. In the middle square of the second register, a large red monster is trying to bite a warrior’s head. This is a popular scene from a story where the warrior, Minamoto Raikō, is attacked by the Shutendōji monster, a mythical oni (demon), who was said to be eating the women in a small town.

While often violent and gruesome, especially for a young audience, these depictions were valued for the stories they imparted.

Explore the entire King

Explore the entire King collection of Japanese warrior prints on eMuseum here.