Ask ROM Anything: Deborah Metsger

Category

Audience

Age

About

Every Thursday at 10 am on Instagram we chat with a different ROM expert ready to answer your burning questions on a different subject. This time on Ask ROM Anything we are talking to Deborah Metsger, the Assistant Curator of Botany at the ROM.

In addition to her responsibilities overseeing the ROM’s extensive botanical collections, Deborah regularly assists other curators with identifying depictions of plants in paintings and as motifs on decorative objects – ceramics, glass and especially on textiles.

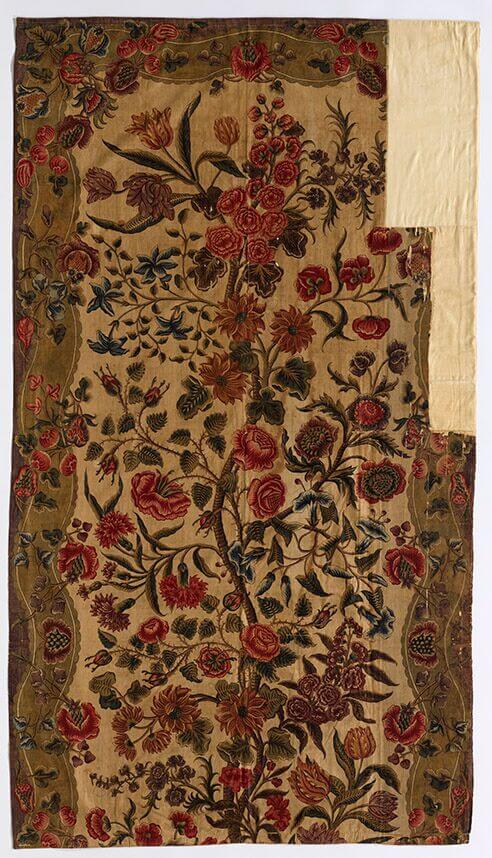

Deborah is the Science Curator for the exhibition The Cloth that Changed the World: India’s Printed and Painted Cottons, on now at the ROM. She is also Curator of its companion exhibition, Florals: Desire and Design.

Florals: Desire and Design explores the connections between the decorative arts and the botanical sciences in Europe in the 1700s – a time when global trade and imperial ambitions brought luxury goods decorated with flowers and novel plants from other continents. It focuses on the different kinds of flowers that were hand painted on the ROM’s magnificent wall hangings and fashions from India and describes their origins and stories. The exhibition shows how botanical illustrations were used as source material for hand-painted decorations on ceramics and textiles. Finally, it asks you to look around and ask the question “Where are the florals in your life?”

Ask Deborah Anything

Q. How did they manage to carefully put floral designs on the materials?

A. Skilled artists hand painted the flowers using a kalam pen and natural dyes. Each piece is made of handspun cotton that was specially prepared to accept the natural dyes. The kalam pen is made from a bamboo shaft that is wrapped with wool to create a reservoir. The artist dips the pen in the dye then squeezes it to paint. They begin by lightly drawing the pattern they want to paint onto the cotton as a template and then paint the colours on one at a time with the kalam pen. The areas that are to remain white, or that have already been coloured are covered with wax, mud, or gums to resist the dye.

This specialized technique was perfected by Indian artists over thousands of years and is being revived by contemporary artists.

Q. Were there any points of contention between the science and culture side of the exhibition?

A. I’m not quite sure what you are thinking of when you say “point of contention” – but I would have to say no.

One of the goals of the exhibition is to show how art and science were and are closely linked – through the medium of botanical illustrations. I often say that botany, the study of plants is the intersection between science and culture. That was certainly the case in the eighteenth century. Prior to that time, botany was really a branch of medicine, and most of the botanists were trained as surgeons. As more and more plants were brought to Europe from other continents – the botanists began to focus their efforts on identifying, naming, and organizing them. Because the plant specimens that arrived were dried and pressed, accurate illustrations were needed to “bring them to life.” These botanical illustrations were important scientific documents but also became advertisements for the new plants that were reaching Europe. They peaked people’s interest in plants and gardens while also sparking scientific curiosity in the natural world. It was very fashionable and a symbol of intellect to have the latest books on natural history subjects including plants.

Q. Are there recurring flower designs/patterns used to indicate a specific mood or feeling?

A. The “language of flowers” to depict mood or feelings didn’t really take hold in Europe until the 19th century – so no, I don't think that patterns indicated a mood or feeling.

Rather, the patterns reflected people’s interests or tastes at the time. The Indian cottons were commissioned by the East India companies. Beginning in the late 17th century the British East India company (EIC) started asking Indian artisans to create designs that were to “English taste”, meaning flowers that were familiar in English gardens or on embroidery. These included rose, tulip, dianthus (carnations), narcissus, morning glory, prunus (cherries), chrysanthemum, and marigold. Carnations and roses are probably the most frequent motifs, but the ROM has other painted cottons (chintz) that are decorated with all the flowers you might find in a garden – including delphiniums and hollyhocks.

Designs also reflected the current fashion of the time. One recurring design is the flowering tree. It became very popular in Europe during the eighteenth century because people were fascinated with the Asian style which was novel and new to them. The flowering tree was first introduced on imported Chinese wallpapers and then as a design on Indian cotton wall hangings. The flowering tree is in fact a hybrid form that draws on European, Islamic, Chinese and Indian traditions.

The interest in an “Asian style” was associated with the import of ceramics and of new “exotic” plants from around the world. The East India Companies catered to this interest by asking for “fancies of the country” – imaginative flowers that were not “English flowers”. That is why so many of the patterns appear almost fanciful.

Q. Are specific flowers used to depict royalty, class etc.?

A. On these pieces no. However – in the eighteenth century owning a floral-decorated piece was a symbol of royalty or high social standing. These were luxury goods that only the rich could afford.

If anything, the kinds of flowers and the colours on the pieces reflect the different countries that they were made for. The Dutch loved tulips, and they also preferred the rich red backgrounds. The English liked roses and they also preferred their flowers painted on a white background – much like that of Chinese porcelain.

Q. What are the most common floral depictions you came across?

A. I am going to answer this from the perspective of both exhibitions.

By far the most common motif on Indian chintz is Dianthus carnation.

These motifs are very distinct and easy to recognize because they have fringed petals with sharp teeth and the base or receptacle is visible, often as a column beneath. These were popular plants in Europe and in Mughal art so they are very common.

On Iranian pieces the Cypress tree is very common. European pieces have a lot of roses and other common garden flowers – lotus iris, and peonies are also very common.

The Chinese and Japanese “the three friends in winter” bamboo, prunus and pine, appear in both exhibitions.

Q. What flowers can we expect to see in the exhibition?

A. Cashews, pomegranates, peaches, elephant apple, cotton, clematis, chrysanthemums, poppies, anemones palm trees, fritillaries, and, many more that truly appear to be fanciful combinations of different plant parts. Even so, I look at them and am reminded of a plant that I know and sometimes can’t just put a name to it.

If you look closely inside the flowers you will see that there is fine in-fill. Some of it is in a geometric pattern but there are others that are based on plants – like the leaves of coriander or seaweed.

One of our hopes for both exhibitions is that people will take the time to look closely and find all these fine details as they are a testament to the incredible skill of the Indian artists that made them.

Q. Were any artifacts in the exhibition hard to display?

A. The wall hangings (palampores) were a challenge to fit because they are so big. In Florals we had originally hoped to put six or seven out and we ended up with four.

Displaying the book Exotic Botany was a challenge because the illustrations are folded and creased and some of the illustrations are on the reverse side. We had hoped to display this sacred lotus, which is one of my favorite illustrations, but it was not possible.

Q. How long would it take an artist to create these fabrics?

A. Estimates are that it would take six to ten artists working together at least six months to complete one of the large palampores.

Q. Who painted the flowers?

A. Indian artisans often in families. The techniques and traditions were passed down through the generations. The two major areas for chintz painting were on the south eastern coast of India and in the regions around Gujarat.

Q. Do you have a favourite floral design in the exhibition, or in the ROM’s collection that won’t be on display?

A. The florals are so beautiful it is really hard to pick a favorite. There is one palampore that was not in good enough condition to display. It was interesting because it shared a border with another palampore, likely meaning they were made in the same workshop. But the plants are all out of this world. I am convinced that some of them are inspired by nature, but it will probably take me years of staring to figure it out.

Most of all I am mesmerized by the craftsmanship. The colours and the fine textures are out of this world. I love the blues and purples. I have come to really respect the different interpretations of the flowers, especially on the fanciful pieces. I love it all!

Q. What is the link to ceramics?

A. As botanical illustrations became more popular, they were circulated in magazines and botanical books. Ceramics manufacturers had their artists hand paint copies of the illustrations onto the ceramics. This was another way to make these fantastic florals available to people for their home décor.

This violet on this Royal Copenhagen Plate is an exact copy of the illustration from the Illustrated botanical encyclopedia Flora Danica. I won't tell you more here – you need to come to the exhibition or listen to the audio tour to hear the whole story!

Q. What drew you to botany?

A. I love plants and always have. I have always been attracted to different kinds of flowers. In university I became fascinated with plant succession and how plant communities developed. I eventually landed in plant systematics and have been working in the herbarium for 40 years. Working in a Museum allows me to explore the cultural connections of plants. Florals: Desire and Design and The Cloth that Changed the World: India’s Painted and Printed Textiles have married my own personal love of textiles with my professional expertise and interests. It has been a real privilege to work on both exhibitions.

Florals has taught me to look around and appreciate how many of the things that we enjoy today – the plants in our gardens, the pattens on the clothes that we wear, are a product of the passions and skills of people in the past. It is great to celebrate them.