Activity: Write Your Name in Egyptian Hieroglyphs

Category

Duration

Audience

Age

Grades

About

Learn how to sound out your name in hieroglyphs, just like a scribe in Ancient Egypt!

Getting Started

Egyptian hieroglyphs weren’t quite the same as the letters of the English alphabet. There were over 500 commonly used hieroglyphs for a student to learn. Some represented a single sound, but others represented more complicated sounds, or even a whole word. Some hieroglyphs don't make any sound at all; they tell you what kind of word the other hieroglyphs are spelling out. For example, after the name of a woman, the scribe would draw a little image of a woman; after a man's name, a little image of a man. Many Egyptian names make little sentences such as Nes mut, which means, "She belongs to the goddess Mut."

When writing out the names of foreigners that wouldn't have any particular meaning in the Egyptian language, Ancient Egyptians would sound them out.

Context

Learning Goals

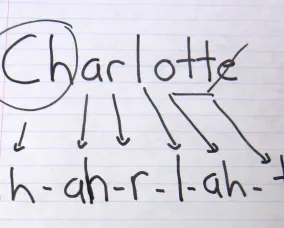

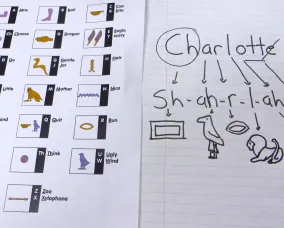

- Deconstruct a name into its phonetic components.

- Understand the difference between letters and sounds the letters make.

- Draw symbolic representation of sounds.

Background Information

For over 5,000 years, people in Egypt used hieroglyphs to write their language. For most of that time, a scribe would have to learn about 500 signs in order to be able to read and write well. Most ordinary people didn't know how to read or write, though they might be able to read and write their own names, or recognize the names of their k

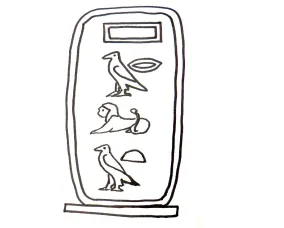

ings, which were surrounded by a loop that we call a cartouche.

Sometimes, Ancient Egyptian names were actually short sentences that expressed their parents' hopes for their new child, or their gratitude to the gods for a safe and healthy birth. For example, the name of a famous king, Ramesses, means "the sun god, Re, caused his birth."

Hieroglyphs are not used quite the same way that letters in the English alphabet are. When writing their names, ancient Egyptians could sometimes take shortcuts and write the symbols for gods or common words, but when writing the names of foreigners, they would have to sound the names out. This could be difficult, since other languages sometimes had sounds that Egyptians found hard to make. If you have ever learned to speak another language, you’ve noticed that not all languages have the same sounds. Sometimes, the Egyptians just had to get as close as they could to the sound of the foreign name

Materials & preparation

Materials

- scrap paper

- good paper

- hieroglyph key (PDF)

- pencil

- pen or marker

- eraser

Preparation

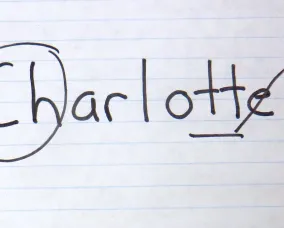

When you write your own name in Egyptian hieroglyphs, it's important to "sound" it out and not write it letter for letter. Sometimes a sound can be spelled different ways. For example, George and Judith both start with a 'juh' sound. If students aren't familiar with breaking their name down into its component sounds, you may want to do a lesson in this first.

Tips

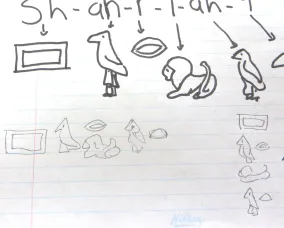

- Long signs can be written above one another

- Use pencil until you have your name the way you want it before going over it with ink

Note: If you want to show that your name belongs to a boy or a girl, you can add one of these symbols:

Boy:

Girl:

Fun fact

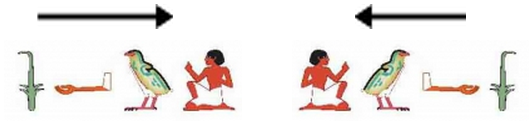

Hieroglyphs can be written from left to right (like English), right to left (like Arabic, Hebrew, or Urdu), or even top to bottom (like Chinese). However you write them, all the faces of the figures should be pointing in the same direction. To read the hieroglyphs, read in the direction that moves toward their faces.

Dig Deeper

Follow-Up

- How does the number of hieroglyphs in your name compare to the number of letters?

- Do you find it easier to write your name in hieroglyphs or English?

- How long do you think it would have taken a scribe to learn to read and write 800 hieroglyphs?

- What would it be like to work as a scribe in Ancient Egypt?

- List some things you might have to read on a daily basis in order to get through your day (reading a cereal box, reading instructions on a piece of technology, reading directions when travelling, reading ingredients on a package, etc.). Now imagine that, as in Ancient Egypt, we have more than 500 commonly-used letters, vowels are usually left out of the words, the writing system was very complex, and there were no public schools to teach people to read or write. Brainstorm some ideas on other ways we could communicate the information in your first list.

Teacher Reflection

- Do the student's answers reflect an understanding of phonics?

- Has the student correctly identified the silent letters, diagraphs, and doubled letters in their name?

- Does the student's hieroglyph reflect an understanding of phoenetic construction?

- Is the student's hieroglyph aesthetically pleasing?

Extension Activities

Put your new hieroglyph skills to the test while decorating a miniature mummy case!

Glossary

Archaeologist: An archaeologist studies the lives of humans who have lived in the past, primarily by examining the objects and other traces they left behind, usually after excavating them.

Book of the Dead: Known to the Egyptians as "The Book of Coming Forth by Day", the text contained spells that would be written on papyrus or painted onto funerary objects that would assist the spirit of the deceased on their journey through the underworld and into the afterlife.

Mummy: A mummy is a deceased human or other animal whose remains have been preserved and do not decay. Mummies occur naturally for a variety of reasons (extreme cold, low humidity, or lack of air), and the earliest Egyptian mummies occurred naturally as a result of being buried in hot sand. Later, Egyptians deliberately mummified their dead as part of an important ritual step to living well in the afterlife.

Coffin: A funerary container for the remains of humans (and occasionally valued animals), often conforming to the basic shape of the body within. In ancient Egypt, usually made of wood or cartonnage.

Sarcophagus: A rectangular stone coffin, which often encloses a wooden coffin that is shaped more like a human.

Cartonnage: An Egyptian building material made from strips of linen or papyrus covered in a plaster-like substance called gesso, using techniques similar to paper maché.