Ask ROM Anything: Fahmida Suleman

Category

Audience

Age

About

Every Thursday at 10 am on Instagram we chat with a different ROM expert ready to answer your burning questions on a different subject. This Ask ROM Anything we discuss Islamic Art and Culture: Medieval to Modern with Dr. Fahmida Suleman, Curator of Islamic Art & Culture at the ROM.

Fahmida joined the ROM in January 2019 after spending 24 years in the UK studying Islamic art and archaeology at Oxford University and working at the British Museum as the Phyllis Bishop Curator for the Modern Middle East. She specializes in religious iconography, Islamic ceramics and the arts of medieval Egypt. Most recently, she published a book on textiles from the Middle East and Central Asia and, once the pandemic is over, she will resume her field research on the silver jewelry traditions of the Sultanate of Oman.

Ask Fahmida Anything

Q. What’s your favourite or the most surprising motif you’ve encountered in your work?

A. This was a tough question, so apologies for taking ages to respond. I think one of the most powerful and deeply symbolic motifs I have studied is the motif of the amuletic hand (khamsa or Hand of Fatima). In my research, I concluded that the amulet originates from an ancient North African context as a symbol of the goddess Tanit as a protection against the “evil eye” or “eye of envy,” and was later supplemented with Islamic notions, including its association with the Prophet’s daughter, Fatima. I also feel that it became a symbol of protection, personal support and feminine spirituality within a patriarchal, text-based religious context for Jewish, Christian and Muslim women. I love wearing my khamsa/Hand of Fatima for this reason. Here’s one from Tunisia (pierced decoration) and one from Morocco (colourful enamel work) that I like to wear.

Q. Can you tell us a bit about your research? It sounds so cool!

A. Thanks! I am crazy about my recent project, which is a collaboration with my colleagues at the British Museum and the National Museum of Oman in Muscat. We are documenting the tradition of female silversmiths in southern Oman. Usually, silversmithing is a male occupation in the Islamic world, but we found a unique context in Dhofar, southern Oman, in which several female silversmiths were producing very delicate and exquisite pieces of jewellery alongside their male counterparts for decades. Unfortunately, the tradition is dying out (for many reasons) and we are in the process of documenting the life and work of Mrs. Tuful Ramadan, a silversmith who is now in her 80s.Here is a picture of our all-female team watching her work. Our research will result in an exhibition in the future.

Q. What discoveries in Islamic Art history/culture are often misattributed to Europeans?

A. I don’t think many people know that the technique of lustre decoration on pottery was invented by potters in the Islamic world. When people think of lustre decoration in western art history they probably think of the glories of Renaissance Italian maiolica wares. However, the first examples of lustre ceramics were produced in Iraq in the 800s AD. The most expensive type of medieval pottery produced, Islamic lustre ceramics gleamed like silver and gold and the recipe was a closely guarded secret among families of potters. They were expensive to make because of the materials required (copper and silver oxide pigments), the double firing required in the kiln (double the fuel), and the final results were hit and miss (waste of time and resources). The technique spread from Iraq to Egypt and then to Iran, Muslim Spain/Portugal (al-Andalus) and from there, to Europe. The ROM has some wonderful examples, such as this human-headed lion with wings from Western Syria made around 1075-1090 AD.

Q. Painting is a commonly used medium in western religion, is it also common in Islamic culture?

A. A wonderful question! By religious painting you probably mean figural painting of humans, I assume? There is a common misconception that the depiction of living creatures (human, bird, animal) is forbidden in Islam (i.e. “haram”). Although the Qur’an opposes the adoration or worship of idols, it does not reject representational art. This is why artistic expression within a mosque does not include figures of people to prevent mental distraction when praying to God. The hadith, or recorded sayings/actions of the Prophet Muhammad in contrast, provide evidence both in favour of and against the prohibition of figural representation. Many medieval scholars argued in favour of images for scientific purposes but also because they triggered an intellectual or emotional response that allowed someone to arrive at a lesson or truth.

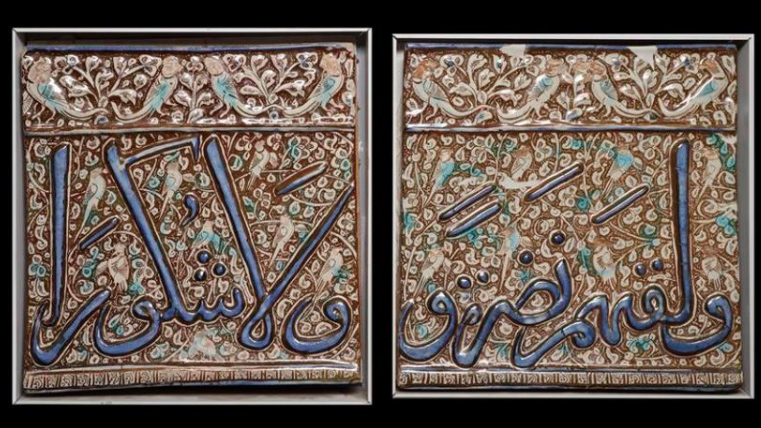

Here is an interesting example for you from the collections of the British Museum. It is a large lustre-painted tile which once adorned the walls of a religious building (for the tomb of a saint called Abd al-Samad) in the city of Natanz in Iran and dates to around 1308 AD. The big cobalt blue letters are part of a Qur’anic verse and they are intermingled with birds and plant motifs. When the tile was produced it was clearly inoffensive to include birds in a religious context, but someone at an unspecified later date carefully chipped off the head of each bird. Maybe this was a misguided act of piety against the depiction of living creatures?

Q. In your experience, how does Islamic calligraphy tell a story beyond the words?

A. Goodness! What a beautiful and poetic question you’ve asked me. As you know Layla, the Arabic script (and other languages that adopted the script, like Persian and Ottoman Turkish) has an elevated status in Islamic culture because the Qur’an, believed to be the Word of God, was revealed in Mecca to the Prophet in Arabic. Before that time, the language was orally transmitted, but after the revelation of the Qur’an it had to be written down for accuracy and memorization. This was the initial impetus for the development of Arabic calligraphy as an art form and there was no stopping the artist and calligrapher from that point on.

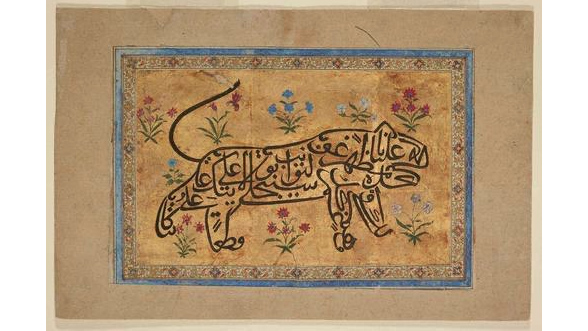

For me, the most exciting aspect of Islamic calligraphy is the interplay between text and image by premodern and modern calligraphers. For example, I love the image of the lion as text in the Aga Khan Museum’s collection ) from 17th-century India. Similarly, the modern British calligrapher Jila Peacock turns the poetry of Hafez into amazing animal forms. There is a meditative quality to this type of calligraphy for me that touches my heart and soul.

Q. What is your favourite piece at the ROM?

A. Hello! This is a really tough question to answer. I have been at the ROM for almost a year and a half now and I am still going through the collections bit by bit and each time I find something new to fall in love with! Since we are in an unusually surreal period in time during the pandemic, I often look at an image of this painting from the collection (I’ve made it the wallpaper on my laptop screen too). It is a painting of a ladies' tea party and is a lovely staying indoors, “self-isolation” image from 19th-century Iran. I’ve described it in detail on ROM collections online. Let me know what you think!

Q. What did medieval Egyptian art look like and what is your favourite piece?

A. Thank you for such a lovely question! Medieval Egyptian art was like no other Islamic art seen before it (of course I’m rather biased). It was sensual, expressive, symbolic and it was a mixture of so many different artistic aesthetics: Coptic, Graeco-Roman, Byzantine, Persian, Chinese, Central Asian, Indian… Between 969 – 1171 AD, Egypt was ruled by the Fatimid dynasty who commanded all kinds of trade networks across the Indian Ocean but also land routes through the Sahara trading African gold and slaves. The land was so prosperous that it attracted artists, craftspeople, merchants and scholars from all over the Islamic world, which greatly impacted the sheer creativity in the arts. It’s so hard for me to choose my favourite piece but to give you a sense of the sensual and expressive nature of the arts of this period have a look at this carved ivory plaque of a female sleeve-dancer made in Egypt between 1050-1150 AD housed in the Bargello Museum in Florence, Italy (inv. no. 80c).

Q. Any female artists that pretended to be men in historic Islamic tradition?

OMG what an AWESOME question! I wish I had an answer for you, but I will start researching that and let you know. There is so little information on female artists in Islamic history. However, it goes without saying that there were so many influential and powerful women in Islamic history. A few were rulers themselves, but others were mothers, sisters, wives, concubines and daughters of Muslim sultans and caliphs that greatly influenced what happened at court and were extremely wealthy in their own right.

I’m thinking of the Prophet’s first wife, Khadija, who was an independent businesswoman and made a marriage proposal to her employee, Muhammad. I’m also thinking of Sitt al-Mulk, the daughter of the Fatimid Egyptian caliph al-Aziz and half-sister of the caliph al-Hakim, who commanded her own special military corps and attempted to overthrow her half-brother in favour of her cousin instead…the stuff of Netflix box sets indeed!

Q. What is a piece of contemporary Islamic Art that you think other people should know?

A. Thank you for your amazing question. Just before the lockdown, I put in an application to purchase several new contemporary works of art by Middle Eastern artists from Canada for the ROM. Because of the lockdown I haven’t managed to buy these pieces yet, but I’m going to highlight one of the artists for you. Her name is Nina Rastgar (b.1988), an Iranian artist working between Iran and Canada, most recently as artist-in-residence at the Queen Gallery, Toronto. Her works are deeply personal explorations on social issues in Iran, especially pertaining to women, feminism, the LGBTQ community and freedom of rights.

I love her banknotes series (Untitled, 2018) which are pen and ink drawings on 500,000 rial notes (approx. $15). Iranian currency dropped in value at a tremendous rate in 2018, and Nina was unable to buy a decent sized canvas for 500,000 rials so she decided to draw on the currency instead.

She plays with the imagery on the banknotes, adding scenes of public protests against the country’s economic policies and people struggling to survive and being trampled on in the process.

Q. Where have you spent the most time during your field research?

A. Aaaahh…you are taking me way back now. Just before I started my Master’s degree at Oxford, I spent 6 weeks on the island of Zanzibar, Tanzania on the coast of East Africa. I was researching the many styles of architecture in the Stone Town of Zanzibar and decided to write my Master’s thesis on a particular building called the Old Dispensary. It was patronised by a powerful Muslim spice trader named Sir Tharia Topan in 1885. Built during the time of British Colonial India, Topan fused the architecture of an Indian-Gujarati mansion (i.e. intricately carved wooden balconies and doors) with European neo-classical elements.

He wanted to build a hospital in honour of Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee, but the building looked like an elaborate wedding cake on the waterfront—a prime location not far from the Sultan of Oman's palace. Topan received his knighthood from the Queen, but he died a year later in 1891 and the project was too expensive for his widow to complete, so she sold it. My time in Zanzibar was eye-opening and amazing. Thank you for helping me remember it. Here’s a picture of the building now which is called the Stone Town Cultural Centre.