The Experience of Colour

From the time we open our eyes

From the time we open our eyes each morning to when those same lids flutter shut at night, we’re surrounded by a kaleidoscope of colour. While we might take it for granted, colour plays an indelible role in the world all around us and how we perceive it.

Everywhere we look in the natural world, colour holds meaning. It evokes emotion, conveys information, signals danger, and offers disguise. Even our language signifies how colour elicits certain reactions—think of the phrases “seeing red” or “feeling blue.”

Human history is marked by fascination with colour—going all the way back to Galileo, who inspired a conceptual shift in how early philosophers began to think about colours.Instead of defining colour as something embedded in objects or organisms, they started to recognize that perception played a major role in understanding colour. This helped pave the way for analyzing colour in terms of the physical properties of light (as Newton did), but it left unexplained the way colours look—the experience of colour.

Nature in Brilliant Colour, a new exhibition opening in December at ROM, shines a light on the brightest and boldest examples of the vital part colour plays in nature, including mysteries hidden in plain sight: animals that change colour to mate or camouflage themselves, plants that cast an eerie glow, minerals that glitter in gleaming hues, even shades of colour that the human eye can’t detect.

But—as Galileo and his contemporaries wrestled with—what is colour, exactly?

“Colour is your brain’s way of perceiving the frequencies of photons that stimulate your eyes,” explains Richard Murray, principal investigator at York University’s Centre for Vision Research. “Different things reflect different frequencies of photons. A red fox reflects low-frequency photons, a green apple reflects mid-frequency photons, and so on. Being able to perceive these properties of light is very useful because it helps you to understand what it is that you’re seeing.”

The human experience of (and response to) colour barely scrapes the surface of how colour manifests itself in nature. Each section of Nature in Brilliant Colour represents the sequence of hues that make up a rainbow. As visitors move through the exhibition, they will discover how colour is just as important in the animal, plant, and mineral worlds as it is in ours.

“Nature is a brilliant artist, using colour to fill the world with beauty. But there is so much more to it than that,” says Courtney Murfin, Interpretive Planner at ROM. “Each colour in nature communicates important messages. Some say, ‘Pick me,’ while others warn, ‘Stay away!’

Each colour in nature communicates important messages. Some say, “Pick me,” while others warn, “Stay away!” Some help animals hide, while others are meant to stand out.

“Some help animals hide, while others are meant to stand out.

“Some help animals hide, while others are meant to stand out. And some aren’t at all what they appear, like polar bear fur (which isn’t actually white!) or a green snake that turns blue after it dies. All of nature’s secret messages are revealed in this exhibition.”

The natural world offers a rainbow of examples: the warning reds of king snakes and velvet ants, the fish and reptiles mirroring the light-reflecting blues and purples of oceans and skies, the earthy yellows and greens that let bees and butterflies hide among the flowers and grass. Colour is inextricably woven into how animals look, behave, and react.

Take camouflage, for instance—a clever tactic that sees animals and plants use colour as a defensive strategy. Also called “cryptic colouration,” camouflaging is used to hide from predators, blend in with surroundings, or mask location or movement. Animals with fur often camouflage themselves seasonally. The Arctic fox maintains a brown summer coat but blends into the snow in winter, when its fur turns white. Birds or fish can quickly shed feathers or scales as needed.

“Colour is so ubiquitous in the animal world that it is difficult to imagine situations where it isn’t relevant. If colour exists, there must be an evolutionary advantage to it,” says Suzanne MacDonald, University Professor in the Department of Psychology at York University.

Colour is also key to mating across species. It is perhaps no surprise that the peacock, with its crown of dazzling turquoise-dappled feathers, is one of the first animals visitors will encounter as they walk into the exhibition.

Animals and insects

Colour perception evolved because it gave animals

Colour perception evolved because it gave animals a ‘leg up’ to be able to use the colours as signals, whether for finding food, attracting mates, or avoiding danger,” adds MacDonald, who has done extensive research on animal behaviour in Canada and Kenya. “So colour is vitally important in animal species that have eyes or other receptors equipped to perceive it.”

For example, the male peacock’s striking jewel-toned tail might seem like a bad way to avoid predators, but it certainly helps entice the females, notes ornithologist Mark Peck, Manager of the Schad Gallery of Biodiversity at ROM.

“Colours are an evolutionary advantage for birds and other species,” Peck says. “The brilliance of their many different colours is what makes birds so beautiful and a big part of why we as humans are so attracted to them.”

How humans and animals

How humans and animals see colours can be very different. It is something researchers continue to study today, both MacDonald and Jacob Beck, Research Chair in Philosophy of Visual Perception at York University, point out. As humans, our visual systems are grounded in three types of photoreceptors, each sensitive to a different wavelength of light. Dogs, in comparison, have only two types of photoreceptors and so are unable to distinguish quite as many colours as we can. No wonder Toronto’s trash-panda mascots leave an explosion of mess behind when they break into the compost bin: raccoons have only one type of photoreceptor, so their weak vision is akin to watching a black-and-white movie.

On the other hand, some animals are able to see beyond the range of human sight or can adapt themselves to that ineffable hue known as ultraviolet.

“Humans are sensitive to a small portion of the electromagnetic spectrum, while bees and butterflies are sensitive to ultraviolet light, and snakes can sense infrared light,” says Beck, who researches animal thought and perception.

“[We have] learned a lot about how colour vision works, but the puzzle of colour experience remains with us today. That’s why we don’t know what colours actually look like to a bird with four colour photoreceptors or to a bee that sees ultraviolet.”

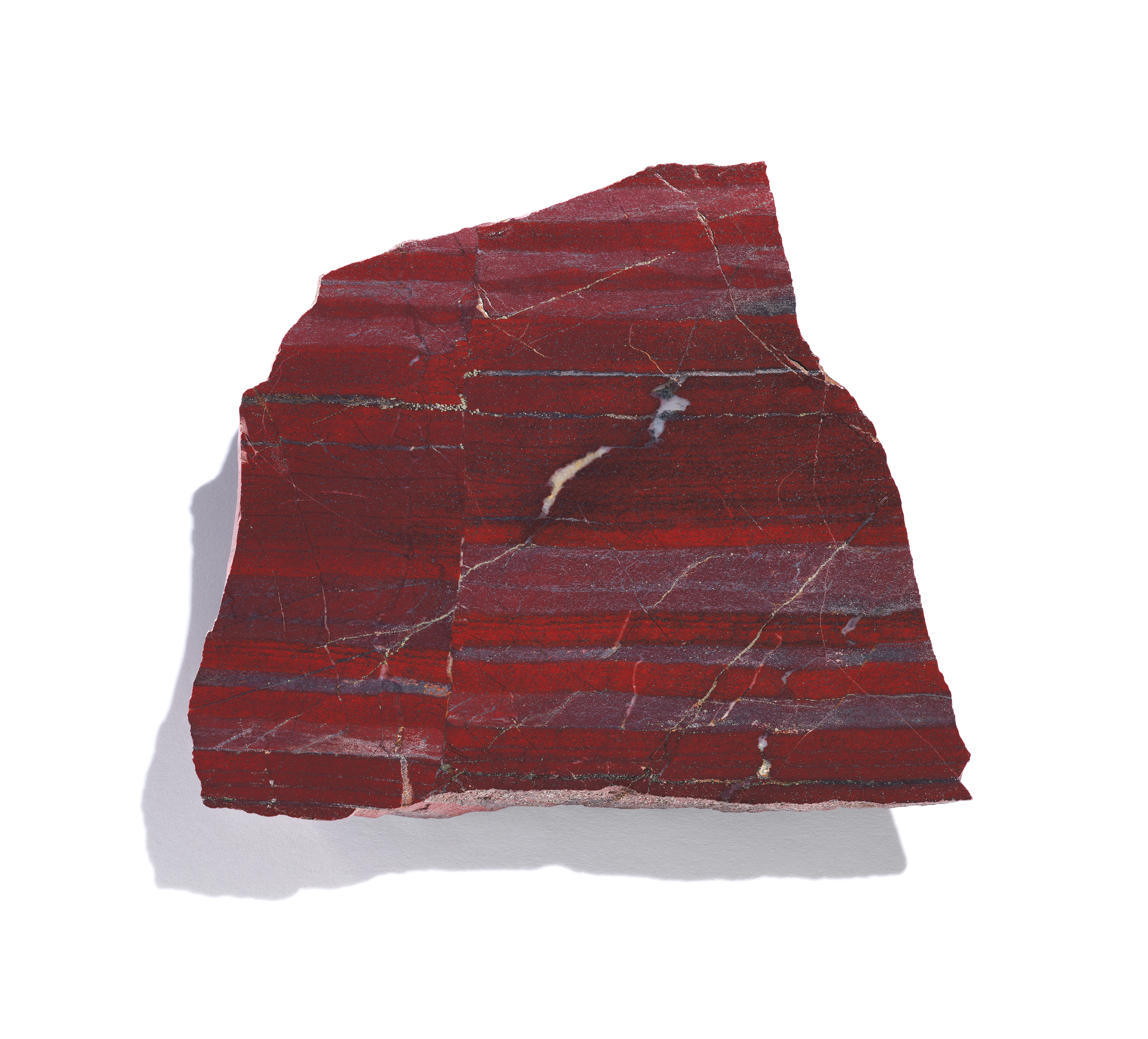

Certain animals, plants, and minerals undergo a drastic colour shift and appear to glow under ultraviolet light—a phenomenon known as fluorescence. Common fluorescent minerals include calcite and fluorite, but some of the eye-catching gemstones on display in Brilliant Colour can also fluoresce when exposed to ultraviolet light.

Minerals and Gems

author line

In fact, the mineral world represents as wide a colour spectrum as the animal kingdom does, notes Kim Tait, lead curator of the exhibition and Senior Curator, Teck Endowed Chair of Mineralogy at ROM. Tait selected many of the show-stopping specimens from the Museum’s vast collection that will be on display in the exhibition.

“You can find every colour of the rainbow in gems and minerals,” says Tait. “Many gemstones have benchmark colours: purple for amethyst, yellow for citrine. Both are the mineral quartz, but it is colour that lends itself to them being called a different name.”

The ways colour touches and shapes our world are boundless. From the bright golden tones of the daytime sun to the shadowy greys after dark, our days are filled with colours that paint a unique picture of our relationship with nature and the way we connect with the ecosystems around us.

“I hope visitors to the exhibition take away that we don’t all perceive colour the same way,” Tait says. “There’s so much to learn about how colour plays a role in nature—and we are only one small part of that spectrum.”

Tabassum Siddiqui is Communications Manager at ROM.