Making sense of Auschwitz

Published

Category

Author

Start

All day and night, trains rumbled into Auschwitz, bringing thousands of Jews, Poles, Roma, and others packed into crowded and filthy freight cars. Upon arrival, the prisoners, carrying what little they had, spilled out onto the platform—a maelstrom of terrified families, snarling dogs, and uniformed SS officers.

“They did not know it, but the new arrivals were about to face selection,” writes Jonathan Freedland in The Escape Artist: The Man Who Broke out of Auschwitz to Warn the World. “If they were sent to the right, they would be marched off first, registered as prisoners and given the chance to work and therefore to live, if only for a while. If they were directed left, their imminent destiny was death.”

Of those condemned to die, very few could grasp what awaited them. This was largely by design, part of the Nazis’ larger plan to placate the very people whom they were trying to murder—all in the service of secrecy and efficiency.

Even as prisoners were herded into the gas chambers, a sign assured them they were in the “Baths.” And in the moments before Zyklon B cannisters dropped into the chamber, filling the room with poison, those same prisoners could look up and see fake showerheads.

The other reason so many arrivals failed to grasp what awaited them was that the very existence of Auschwitz—the largest documented mass murder site in human history—was almost impossible to fathom.

The very existence of Auschwitz—the largest documented mass murder site in human history— was almost impossible to fathom.

Second

“It was completely unprecedented,” says Dr. Robert Jan van Pelt, a professor at the University of Waterloo School of Architecture, renowned Holocaust scholar, and lead curator for Auschwitz. Not long ago. Not far away. “Prisoner camps had certainly existed since the late 19th century, when it became possible to produce cheap barbed wire and prefabricated barracks on an industrial scale. But the idea that you would have places where massive amounts of people would be brought without any judicial process and then put into situations of total starvation, abuse, and slave labour—this had never happened before in history.”

While the scale of the camp was certainly unprecedented, historians studying Auschwitz today have access not just to victims’ testimonies but to mountains of archival evidence from the Nazis themselves. “In 1945, because of the defeat of Nazi Germany, because of the bombings, all of the evidence could be found if not literally on the street, then at least metaphorically,” says van Pelt. “And the Americans went into the now forcefully opened archives of the German state to collect the evidence to be used in the Nuremberg trials.”

Yet even with the wealth of archival evidence and survivors’ testimonies, the enormity of the Holocaust remains difficult to comprehend—a fact that “plays into the hands of deniers,” van Pelt says.

So given how hard it is to understand, how do you teach people about Auschwitz and the Holocaust? For van Pelt, the answer is in the sprawling exhibition he helped create: Auschwitz. Not long ago. Not far away.

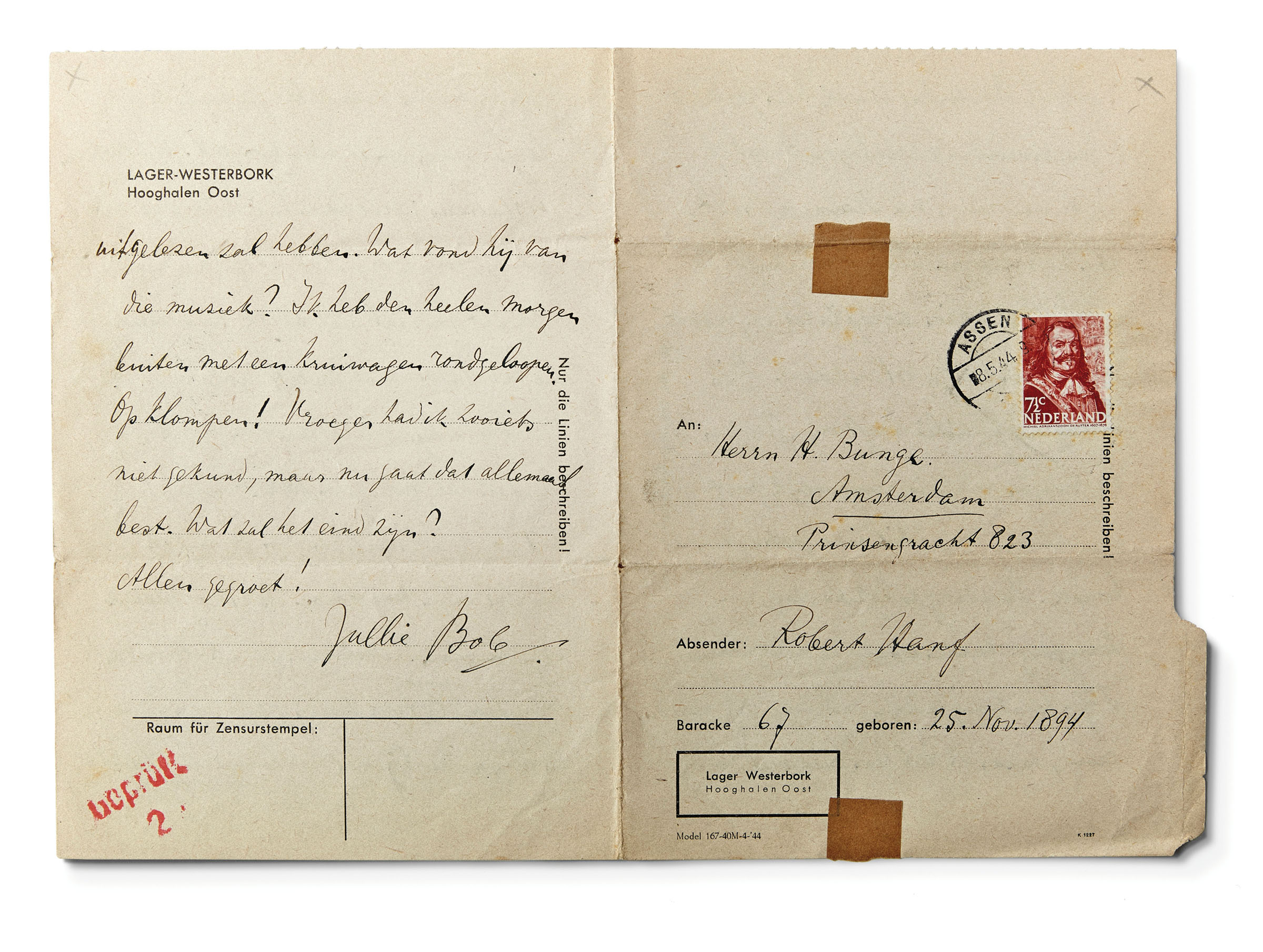

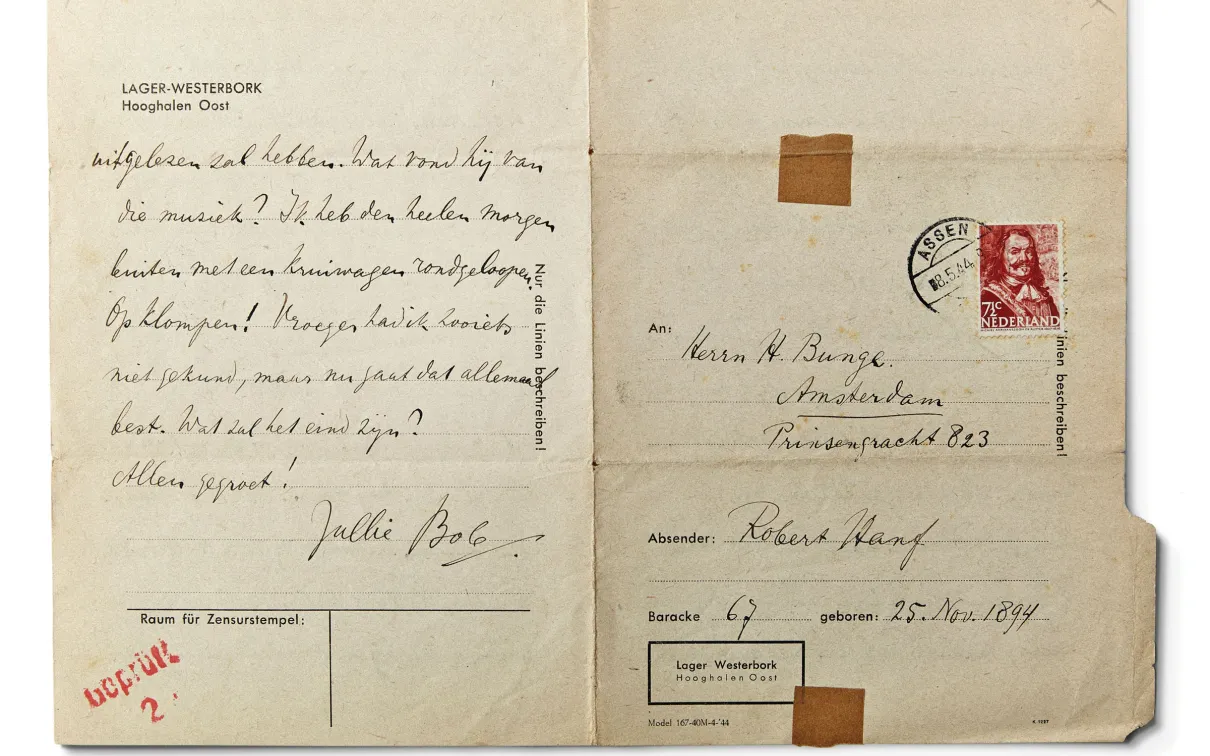

Now on at ROM, the internationally touring exhibition created by Musealia, co-produced by the Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial and Museum in Poland, and developed with an esteemed international panel of curators and historians is one of the most comprehensive exhibitions ever presented on the subject. Survivor testimonials, historical documents, and first-hand accounts by emancipating forces create a powerful connection to the exhibition’s more than 500 original objects—many of which have never been seen before in Canada—on loan from the Auschwitz Memorial and more than 20 other major institutions and private collections around the world.

Throughout the exhibition, many other such personal objects— victims’ hairbrushes, buttons, and eyeglasses—hint at the scale of devastation. 'Ultimately, the Holocaust’s most shattering impact is at the intimate level,' says van Pelt.

Three

While the volume of material seems overwhelming, the presentation of it is remarkably restrained. Luis Ferreiro, the Director and CEO of Musealia, who first conceived of the exhibition, wanted to “present facts and artifacts almost forensically.” His inspiration, both for this approach and the exhibition, was Man’s Search for Meaning, a Holocaust memoir in which the author, psychiatrist Victor Frankl, articulates his theory that the pursuit of meaning is the foundation of mental well-being.

“[Frankl] doesn’t make you feel this or that or push you to cry,” Ferreiro says. “It’s just somebody touching you gently, not shaking you, not forcing you, because, in the end, change is something only each one of us can make in ourselves.”

This restraint and almost forensic approach to the material is woven throughout the exhibition. In fact, it’s apparent in the very first artifact we see: a single red women’s dress shoe. Ever since the Soviet Red Army discovered mounds of shoes while liberating the first concentration camps, shoes have become a potent symbol of the Holocaust. For as van Pelt notes, unlike clothing, “The shoe continues to carry the imprint of the body” and the “presence of the other.” This red dress shoe is particularly affecting because it suggests that its owner imagined a life beyond Auschwitz—a life of pleasure and parties and dancing.

Throughout the exhibition, many other such personal objects—victims’ hairbrushes, buttons, and eyeglasses—hint at the scale of devastation. “Ultimately, the Holocaust’s most shattering impact is at the intimate level,” says van Pelt.

But as often as the exhibition zooms in, it zooms out, providing essential context about World War I, the Weimar Republic, the history of anti-Semitism, and the rise of Nazism. For Ferreiro, these sections of the exhibition also provide answers to some of the most fundamental questions about the Holocaust. “How was it possible for one of the most technologically and scientifically advanced societies of its time to turn to genocide?” asks Ferreiro. “How was it possible for neighbours to betray their neighbours and to become silently complicit in such a genocide?”

While Auschwitz asks us to bear witness, it also invites us to come together—and imagine a different future. That’s central to the work of a great museum like ROM.

Four

Josh Basseches, ROM Director and CEO, adds that the exhibition’s many objects, “combined with the searing testimony of survivors, speak not just to the horrors of the Holocaust, but to the systems, people, and beliefs that allowed it to happen.” Basseches continues, “While Auschwitz asks us to bear witness, it also invites us to come together—and imagine a different future. That’s central to the work of a great museum like ROM.”

The exhibition is also clear eyed about the dizzying scale of the crimes. “1.3 million people were deported to Auschwitz,” writes van Pelt in the Auschwitz. Not long ago. Not far away. catalogue. “Of these, more than 1.1 million perished in that camp: 1 million Jews, from Hungary, Poland, France, and a dozen other European countries; seventy-five thousand non-Jewish Poles; twenty-one thousand Roma; fifteen thousand Soviet prisoners of war; and up to fifteen thousand people who fall into other categories.”

Even when the exhibition zooms out, it never loses sight of Auschwitz as a physical reality, which for van Pelt, a professor of architecture was essential. “One of the things that we try to do in this exhibition, right at the very beginning, is to give the visitor a clear sense of the place—and repeat,” he says. “We talk about the town. We talk about the region. We locate the town before the camps were created.”

five

By “continuously reinforcing” the geography of Auschwitz, van Pelt says visitors can better visualize the architecture of the camps in their minds, allowing them “to understand this very chaotic reality.”

Then once that geography and broader history has been established, the exhibition takes visitors deep inside the concentration camps. Here, large artifacts, like a concrete post and a section of a wooden barracks, reinforce that sense of place, while smaller ones, like a pair of black SS jackboots placed at a child’s eye level, give a sense of the victims and their perpetrators.

One such artifact is a hulking rusted metal street sign reading “Auschwitz Kreis Bielitz” (Auschwitz District Bielitz)—evidence, says van Pelt, that the city of Auschwitz was “a fully functioning municipality.”

Another is the large wooden desk that belonged to the Auschwitz commandant Rudolf Höss, the focus of Jonathan Glazer’s Oscar winning 2023 film Zone of Interest. At first glance, the desk is unremarkable save for the eight artifacts—including a photograph of Adolf Hitler and another of the commandant’s family—adorning its surface. But then, as Ferreiro says, Höss’s “upside-down” world comes into focus.

At this very desk, a man sat down, organized his papers, and committed himself to the task of finding a better, more efficient way to extinguish an entire people.

Six

Colin J. Fleming is Senior Creative Communications Strategist at ROM.

Sponsors

Exhibition Patrons: Colliers International Group; Wendy & Elliott Eisen and Family; FirstService Corporation; Fogler, Rubinoff LLP; Freeman Family; Lillian & Norman Glowinsky and Family; Ira Gluskin and Maxine Granovsky-Gluskin; Goldman Sachs Canada Inc.; Louis and Garry Greenbaum and their Families in memory of Morris and Helen Greenbaum z'l; Brown and Lindenberg Families; Metropia; Power Corporation of Canada; The Rechtsman & Silver Families; Rochelle Reichert & Henry Wolfond; The Edward and Suzanne Rogers Foundation; Shael Rosenbaum; The Schulich Foundation; The Gerald Schwartz & Heather Reisman Foundation; Isadore and Rosalie Sharp; Larry and Judy Tanenbaum Family Foundation; Temerty Foundation; Torys LLP; The Jack Weinbaum Family Foundation; Ted and Annette Wine & Family; Anonymous (2).

Community Partners: Andrea and Michael Barrack; Judy Bronfman Bernick and Howard Bernick; Sari and David Binder; Rocco and Irene Pantalone, Penny Offman, Harry and Dora Kichler and Simon and Jan Zucker; Paul and Tanya Braun; Helen Burstyn; CIBC; The Ricky and Peter Cohen Family Foundation, Moez and Marissa Kassam Foundation, The Levy Family Foundation, Albert Sliwin and Family; Myrna Daniels; Kiki and Ian Delaney; Susan, Perry, Taylor and Nicholas Dellelce; Focus Wealth Management and Hazelview Investments; George and Kitty Grossman; Cory Hawtin; Mark Hilson and Kathleen O'Keefe; Pierre Lassonde Family Foundation; Geoffrey S. Belsher; Gregory S.Belton C.M., C.V.O, LL.D; Wayne Squibb; Rosamond Ivey; Pamela Pastoll Jacobson, Ian Jacobson and Families; Khrom Capital; KingSett Capital; Northbridge Capital Inc.; Andrew Pastor and Nicholas Telemaque; RBC Foundation; Heather Regent Family Charitable Foundation; Jill Reitman and Joel Reitman, C.M.; RioCan REIT; Larry Rosen & Susan Jackson; Robert Rubinoff; The Shen Family Charitable Foundation; Ken Shi & Yvonne Lou; Elsa Stringer and Shephen Stark; Fran and Ed Sonshine; TorQuest Partners; The Venn-Mitchell Family; Bunny Adler Vyner and Brian Vyner honouring Gabriella Adler, an Auschwitz survivor, born in 1926 - ; Anonymous.

This exhibition is generously supported by the Royal Exhibitions Circle.