Egyptian Mummies

Ancient Lives. New Discoveries.

Date

About

Who They Were. How They Lived.

Mummies have captured our imagination throughout time. Uncover the secrets of six mummified individuals from ancient Egypt in this compelling exhibition from the British Museum. Using the latest technology explore how these people lived along the Nile and what happened to them after they died.

Egyptian Mummies: Ancient Lives. New Discoveries. presents unique insights into six mummies spanning 900 BCE to CE 180 including a priest’s daughter, a temple singer and a young child. Combining CT scans, digital visualizations and the latest research, this exhibition offers a fascinating glimpse into these ancient lives. Each mummy has a story to tell.

Descriptive Audio Tour

Egyptian Mummies: Exploring Ancient Lives

descriptive audio tour

Stop 1

Welcome

Welcome to Egyptian Mummies: Exploring Ancient Lives. This exhibition was

created by the British Museum, to highlight extraordinary research into the lives

of six mummies. Through non-invasive techniques like CT-scans, the British

Museum has been able to construct a more nuanced portrait of life in ancient

Egypt over a thousand-year span. It is our great pleasure to bring this research to

the Royal Ontario Museum and share it with you.

Please be advised that this exhibition contains mummies and digital displays of

human remains from the British Museum. The ROM also holds and cares for some

human remains, to expand our knowledge of ancient cultures. When we make the

decision to display remains, it’s to broaden our understanding of the ways people

lived and cared for their dead – and with the support of the related communities

or places of origin.

This descriptive audio tour will introduce you to the six lives that make up the

heart of this exhibition. We’ll also explore other themes around daily life in

ancient Egypt. From jobs, health, hobbies, and diet, we hope you’ll find a few

surprising connections with their world.

Greeting you at the entrance to this exhibition are two projections of Anubis.

Anubis was an important god to the ancient Egyptians. He is depicted as human,

but with the head of a jackal – a wild animal in the same family as wolves,

coyotes, and dogs. The ancient Egyptians associated jackals with the afterlife

because they often saw these animals in cemeteries.

As you travel down the hallway to your right, you enter a dark space. Tiny lights

hang overhead, mimicking a star-filled sky. Under your feet is an image of the

Nile, the longest river in the world. In both ancient and modern Egypt, the Nile is

extremely important. Its waters and fertile soil help life thrive in the middle of a

desert.

At the end of the hallway is a wooden model of a funerary boat. It’s about the

length of an adult’s arm, and brightly coloured. The yellows and greens that make

up the boat have stayed vivid for over a thousand years. The boat carries three

figures surrounding a tiny mummy on a funerary bed. The two women at either

end of the bed likely represent Isis and Nephthys. They were sisters of Osiris, the

god of the afterlife. The man sitting at one end of the boat may be a priest,

reading rituals that helped the deceased reach the afterlife. This model

represents the deceased’s journey to the tomb and, symbolically, to the afterlife.

Here’s where your journey begins. In the first space, you’ll encounter the mummy

of Nestawedjat, a woman who lived in Egypt almost three thousand years ago.

Find out in the next section how researchers construct the life of someone who

lived so long ago.

Stop 2

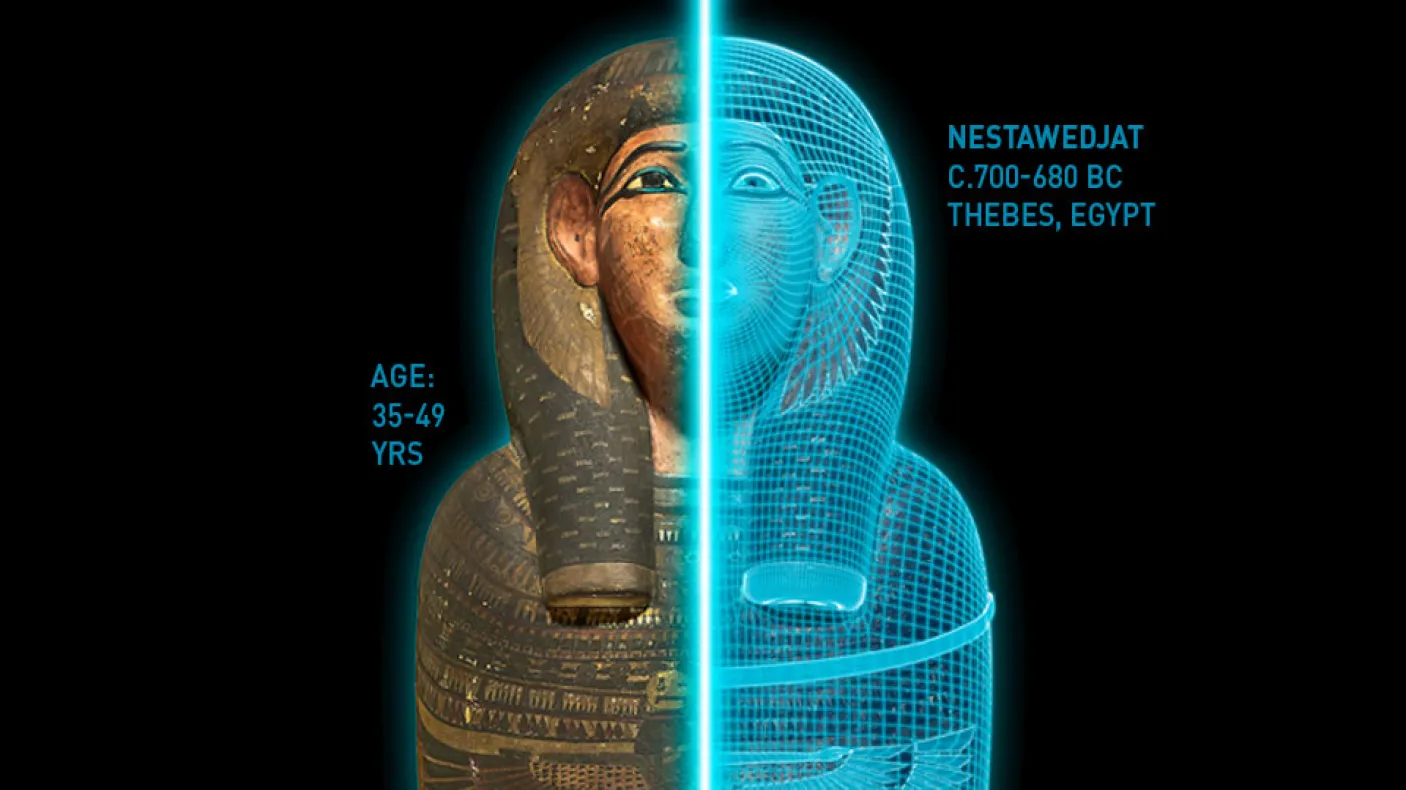

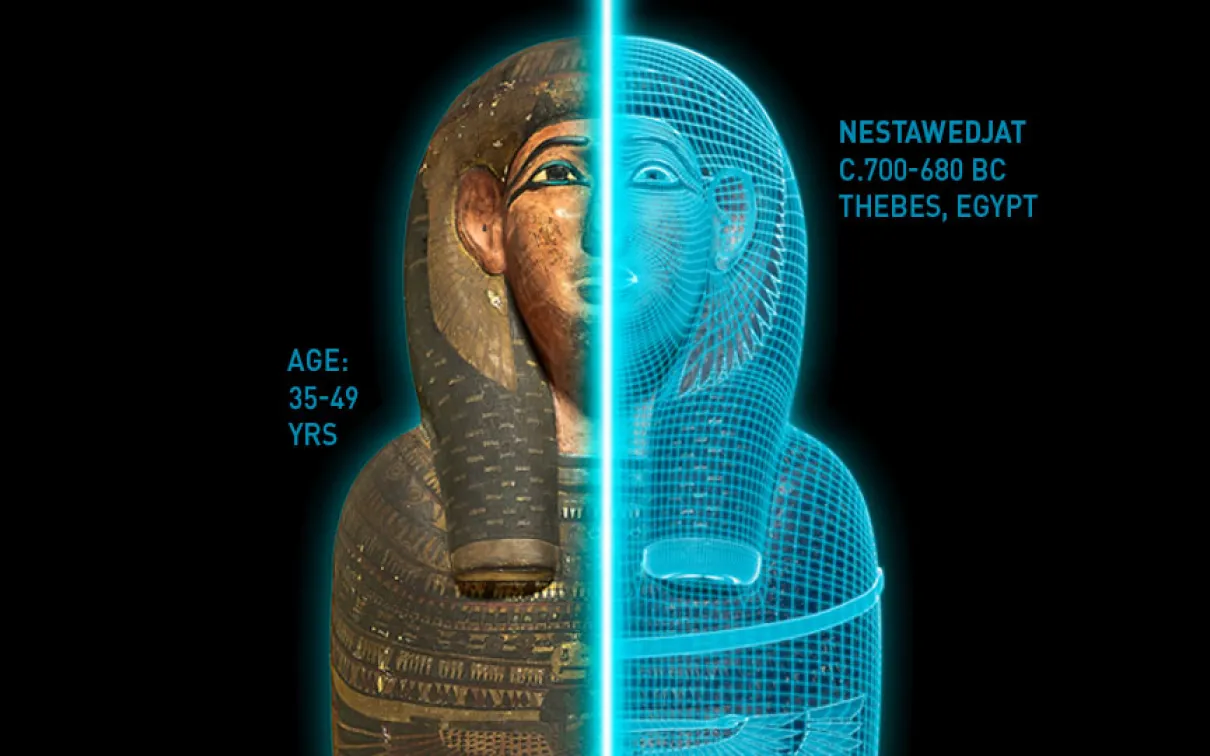

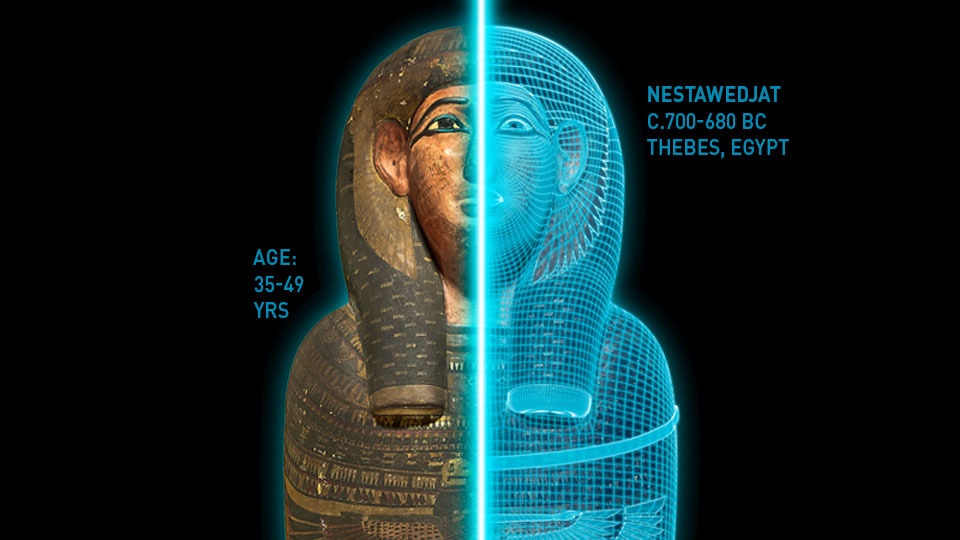

Nestawedjat: A Married Woman from Thebes

In this space are three large coffins. The case on your left contains the mummified

body of Nestawedjat. She was an upper-class woman who died around seven

hundred BCE. The other cases contain her outer, middle, and inner coffins.

They’re a bit like Russian nesting dolls – one coffin fits inside the other. Coffins

were among the most important items of funerary equipment. They were

believed to magically protect the deceased and symbolize a rebirth into the

afterlife. Her inner coffin shows a likeness of a woman, gazing upwards. Her eyes

are lined in heavy black kohl liner. An image of the goddess Nut appears on the

front. Her wings span the width of the coffin.

‘Nestawedjat’ is a woman’s name, but British Museum staff had long wondered if

these coffins actually contained a woman’s remains. In the nineteen sixties, early

x-rays indicated the mummy of a man. However, with a CT scan, researchers have

since confirmed these were a woman’s remains. Without unwrapping her linen,

they could examine her pelvis and the shape of her hipbones to confirm her sex.

Wear on her pelvis joints reveal she was between thirty-five and forty-nine when

she died. This sounds young to us, but she lived a long life for an ancient Egyptian.

Researchers also noticed how well-preserved Nestawedjat’s mummy is. It’s a

perfect example of the careful mummification process that was central to

funerary beliefs.

Mummification was so important to ancient Egyptians because they believed a

mummified body was the keeper of a person’s three souls. The first soul, or ‘ka’,

was the person’s double and stayed in the tomb with the body. The second, or

‘ba’, was a human-headed bird, and was free to travel at will. And finally, the

‘akh’, was the blessed or transfigured spirit, which entered the Afterlife. These

spirits might be lost if the body was destroyed through natural decomposition.

To preserve the body, special priests called embalmers removed most of the

internal organs soon after death. They removed the brain by making a small hole

in the deceased’s nose and pulling the tissues out. The embalmers then dried the

body in a natural salt called natron for about thirty-five days. Finally, they

wrapped the body in many layers of linen. In some places, Nestawedjat’s linen is

as thick as the length of an adult’s thumb.

Embalming had both practical and spiritual dimensions. The ancient Egyptians

believed it was overseen by a divine power – Anubis, the jackal-headed god who

greeted you at the beginning of the exhibition. You’ll hear more about him at the

next stop.

Stop 3

Anubis and embalming

In ancient Egyptian religion, Anubis is both protector of the burial ground and

inventor of embalming. According to legend, he performed the first

mummification on the body of the god Osiris, who then became Lord of the

Afterlife. During the embalming process, the priests were meant to embody

Anubis’ spirit. In fact, some might have worn jackal masks during mummification.

The jackal is a close cousin to wolves, coyotes, and dogs. Ancient Egyptians linked

Anubis to the afterlife because they often spotted jackals lurking in burial

grounds.

In nature, jackals typically have light reddish-brown fur with a grey patch on their

back. However, in ancient Egyptian art, Anubis is always jet-black – the colour of

rebirth. This association comes from the Nile river. When the Nile flooded, the soil

along its banks turned a rich black, reviving the farmlands and signifying the

beginning of the growing season. Naturally, the god that helped the deceased

achieve immortality – a spiritual rebirth – would be black too.

Nearby is a small Anubis sculpture. It’s metal and was made between six sixty-four

and three thirty-two BCE. It’s small – about the size of an adult’s index finger. Its

surface is almost black aside from a bright glint in its eyes, where the artist added

small gold inlays.

In the next section you’ll encounter a temple singer. She worshipped in the cult of

Amun, whose priesthood was an incredibly powerful and influential religious

group.

Stop 4

Tamut: a chantress of Amun

Tamut was a singer in the Temple of Karnak, the city of Thebes’ most important

religious centre. She and her father, a priest named Khonsumose, both worked

among the priests running the cult of Amun, the most powerful god in Egypt. His

name means “the hidden one.” Both Tamut and her father took part in religious

rituals at the temple.

Amun-worship was widespread in Egypt by Tamut’s lifetime. The temple at

Karnak was massive – its ruins show us it was one of the biggest religious

complexes in the world. Karnak was so influential that the high priests running the

temple even challenged royal power at times.

Tamut’s mummy is covered by a cartonnage case. Cartonnage looks a bit like

papier-mâché. Makers used linen, plaster, and glue to create a hard outer-shell

that protects the mummy. An artist has covered Tamut’s cartonnage case with

colourful religious scenes. In one image on the coffin’s front, Horus, the falcon-

headed god of the sky, leads Tamut to a company of gods. The crowd includes

Osiris and his sisters Isis and Nephthys. Even though the cartonnage is almost

three thousand years old, much of the colour is still vibrant.

Like Nestawedjat, the first mummy you encountered, researchers believe Tamut

was between the ages of thirty-five and forty-nine when she died. We see this age

reflected in the wear and tear on her joints.

CT scans also reveal that she had dental disease and plaque in her arteries. Plaque

can lead to strokes and heart attacks. Today, cardiovascular disease is regarded as

the main cause of death in the developed world. Mummies like Tamut show that

the disease has a longer history than we previously thought.

Tamut’s CT scans revealed a lot of information around health in ancient Egypt. But

the British Museum’s research team also noticed something intriguing that helps

us understand more about the cultural practices around death in ancient Egypt –

specifically magical rituals. Continue the audio tour when you’re ready to hear

more.

Stop 5

Amulets

Tamut’s mummy offers an incredible record of disease in ancient Egypt. But under

the wrappings are items that reveal cultural – and magical – practices around

caring for the dead.

CT scans show Tamut’s body is covered in amulets and other protective items.

Objects like these were believed to have magical powers that protected the dead

and helped them achieve immortality. Amulets came in many different forms,

including gods and animals. But it wasn’t just an amulet’s shape that made it

powerful –the colour, the materials used to make it, or the spiritual words used to

activate it, were also factors.

Tamut has an amulet of a winged goddess curved around her neck, in the form of

a kneeling female figure with outstretched wings. The figure is probably Nut,

goddess of the sky and eternal mother of the deceased.

On one of Tamut’s breasts is an amulet of the sun god Ra-Horakhty. He appears in

the form of a falcon, a large bird that’s like a hawk. Artists often depicted him on

coffin lids. He symbolizes the renewal of life through the power of the sun.

A vulture-shaped amulet rests on her pubic area. Vultures often represent the

goddesses Nekhbet and Mut, who are associated with birth and rebirth.

Narrow leather bands called stola run from Tamut’s shoulders to her stomach,

crossing at her chest. Stola were considered the trappings of the gods – in fact,

depictions of Osiris often show him with similar chest straps. Stola were probably

meant to provide divine status to the deceased.

Nearby are amulets that were common in ancient Egypt – the djed pillar, the

heart scarab, and the wedjat eye. All of the amulets are small and would fit in the

palm of your hand.

The djed pillar symbolized stability and endurance. It’s shaped like a small

column, with four ridges at the top. It’s a reference to Osiris – the god of the dead

– and his backbone. The Egyptian Book of the Dead, a collection of magical spells

believed to guide the deceased’s journey into the afterlife, contains a reference to

the djed pillar: ‘Raise yourself, O Osiris, you have your backbone…’

Among the most important amulets were those in the form of a scarab beetle

inscribed with spell 30B of the Book of the Dead. Spell 30B reads in part, “…O my

heart, the heart of (my) mother! O my heart of the different forms! Do not stand

up as a witness in the presence of the Balance. Do not be opposed to me in the

Tribunal.” The Egyptians believed these words would prevent the heart from

revealing a person’s wicked deeds when judged in the hall of Osiris.

The wedjat, or Eye of Horus, was one of the most popular amulet styles.

According to myth, the god Horus’s right eye was injured in battle, but later

magically healed.

The wedjat eye became a symbol for integrity and the state of being whole.

Believers saw it as a protector from injury or harm. The lines beneath the eye are

a reference to markings around the eye of a falcon, the bird used to represent

Horus. The embalmers who prepared Tamut’s body for mummification placed

two metal plates with engraved wedjat eyes over cuts in her abdomen, as a form

of magical healing.

In the next section, you’ll encounter a priest who reveals quite a bit about dental

health in ancient Egypt.

Stop 6

Irthorru: A Priest from Akhmim

You’ve arrived at Irthorru’s mummy and coffin. Researchers believe he was

between the ages of thirty-five and forty-nine when he died.

Irthorru was a priest who lived in Akhmim, a town on the Nile River. In ancient

Egypt, most priests served one month out of four. During their off time, they

worked outside of the temple or served in another sanctuary. Individuals could

hold several priesthoods at the same time. Their role was prestigious and

lucrative – daily food offerings were probably shared among the priests after

being offered to the gods. By Irthorru’s lifetime, most positions were inherited.

Many members of his family served in the priesthood.

An artist has painted various scenes across Irthorru’s coffin. In fact, illustrations of

Irthorru appear in several. As a living person, he is introduced to the gods of the

afterlife by Thoth, the god of wisdom, magic, writing, and the moon. Below the

scene lies his mummy. Soaring above his body is his ba spirit in the form of a bird

with a human head. This suggests his ability to travel between the afterlife and

the world of the living.

Irthorru’s face is covered in a gilded mask with a false beard. It’s a perfect face for

eternity – gold symbolized the skin of the gods. Masks like these usually covered

the whole head of the deceased, but CT scans reveal this mask only covers

Irthorru’s face. It’s an unusual feature for mummification during this period.

The scans also revealed Irthorru had extremely poor dental health. He had

numerous lesions that were probably abscesses – infections that would have

released pus – which would have probably been very painful.

We don’t know why Irthorru had such poor dental health, but research by the

British Museum may offer some clues. Analysis on thirty different bread loaves

from their collection revealed many surprising ingredients – stones, sand, and

chaff, a grain casing that humans can’t digest. These coarse additions may have

caused the heavy wear observed in some ancient Egyptian mummies’ teeth. Such

dental wear would have allowed the bacteria of the mouth to enter the pulp

chamber – that’s the centre of the tooth - causing an infection.

We’ll shift from the mouth to the top of the head in this next section and explore

hair. In today’s world, hair carries so much meaning and significance – and the

same was true, thousands of years ago, in ancient Egypt.

Stop 7

A Temple Singer from Thebes

The number of unearthed styling tools tell us haircare was serious business in

ancient Egypt. Men usually shaved their faces. Tweezers helped both sexes

remove unwanted growth.

Hair could also be symbolic. Styles and length could reveal information about age,

sex, and social standing.

Although we don’t know her name, the inscription on this woman’s cartonnage

case tells us that she was a priestess. It’s possible she had a high status in society

too. When researchers reviewed her CT scans, they noticed she had extremely

short hair – a cut that may indicate she wore wigs for special occasions. Both

high-ranking men and women wore elaborate wigs of human hair with their

natural hair cut short or shaved. These status symbols concealed receding

hairlines and discouraged lice – a big problem for many ancient societies.

This priestess lived in Thebes around eight hundred BCE and probably worked at

the temple of Karnak. CT scans show that she was probably between thirty-five

and forty-nine years old when she died.

A painter has decorated her cartonnage case in colourful scenes that offer divine

protection. On her chest is a falcon with a green ram’s head. There’s also a red

circle symbolizing the sun god Ra emerging at dawn.

The scans reveal the embalmers placed a few different amulets under her

wrappings, including one shaped like a headrest. The headrest is u-shaped and

supported by a thick base. The Book of the Dead explains the magical functions of

the headrest. It elevated the head of the deceased, in reference to the sun god’s

rise in the east each morning. It was also believed to offer magical protection

against decapitation.

Like Irthorru, the priest in the previous section, these CT scans also show various

dental diseases – bread was a staple for all levels of society, and perhaps those

rough ingredients wore down her teeth, too.

Based on what we know about religious life in Egypt, it’s likely the priestess

played musical instruments during spiritual ceremonies. You’ll hear a bit more

about ancient Egyptian music in the next section.

Stop 8

Musical Instruments

Music was an important part of ancient Egyptian life – we see performance

depicted in different types of art, including paintings and carvings. We also have

many examples of musical instruments – different types of drums and shakers, as

well as flutes and string instruments, like lutes and harps. These give us a general

idea of the types of sounds instruments made, but we don’t know exactly what

melodies or hymns were like – there aren’t any examples of arrangements.

The god Bes, protector of households and families, was associated with music.

Artists usually depicted him dancing or playing the tambourine while sticking out

his tongue, as a way of warding off evil forces.

The next section focuses on the symbolism of the family in ancient Egypt. It also

features an alcove, containing the mummy of a young child who died during the

period of Roman rule in Egypt. Objects that explore the importance of the family

structure and childhood in ancient Egypt are outside of the alcove.

Stop 9

A Young Child from Hawara

We know little about the ancient Egyptians’ beliefs about children in the afterlife.

Few children received elaborate burials, perhaps because many died young. But

during the Roman period, which began in thirty BCE and ended in six-forty CE, the

practice increased. Researchers have located many examples of mummified

children at different burial sites.

During Greek and Roman rule, residents of the city of Arsinoe buried their loved

ones in the cemetery at Hawara. Some graves at the site often contain several

bodies. This young boy was discovered with other mummies, including a woman

and two children. We do not know if this group was related.

CT scans confirm this boy was around two years old when he died. His spine and

ribs show damage which may have happened during mummification. Many layers

of bandages cover his body. His cartonnage mask is gilded with intricate

decoration, suggesting he came from a wealthy family. The cartonnage also shows

traditional scenes, such as a priest – or maybe the boy himself – performing

rituals and presenting offerings to the gods. On the back of the mask an artist has

painted a scene showing the child being purified in life-giving waters by the gods

Horus and Thoth. Horus is falcon-headed. Thoth has the head of an ibis, a bird

with a long, pointed beak. Both gods have human bodies.

The family unit was central to life and was often explored by artists and sculptors.

For the ancient Egyptians, the ideal family unit contained a father, mother, and a

child. This grouping was also echoed in religious art. Many works show Osiris and

Isis together, with their child Horus.

This child passed away during the first hundred years of Roman rule over Egypt.

Until about three hundred CE, some burial traditions remained the same. But the

era saw new practices too. In the last section, you’ll hear how methods shifted as

ancient Egypt entered a new age.

Stop 10

A Young Man from Roman Egypt

Mummification continued under Roman rule, but techniques and styles changed

over time. One major shift was the ‘mummy portrait’ – wooden panels that

showed the deceased as they appeared in life. Despite this change, funerary

practices still centred around the deceased’s rebirth into the afterlife in the

footsteps of Osiris.

CT scans reveal this young man skeleton has nearly finished growing and he died

between the ages of seventeen and twenty. His mummy portrait shows a young

man with dark curly hair, large expressive eyes, and thick eyebrows. His face is

slim, but CT scans show he was significantly overweight when he died. He also

had significant tooth decay – perhaps his diet was high in sugar and starchy foods.

The shroud that covers his body is unusual because it’s plain. During this era,

funerary shrouds usually had elaborately painted scenes or complex criss-crossed

bandage patterns.

You’ve almost reached the end of the exhibition. Before you go, spend a bit of

time with the short film at the end. You’ll learn that the study of ancient Egypt has

come a long way since the eighteen hundreds. While x-rays made in the nineteen

sixties helped uncover some information, today’s CT scans provide details that

would amaze early Egyptologists. As technology improves, we’re able to answer

questions we thought we’d never solve. And that leads us to wonder – what will

tomorrow’s researchers discover? How will we refine our understanding of life

and death in ancient Egypt? What more can we learn from the people beneath

the wrappings? And what could an ancient Egyptian exhibition look like in twenty

years?

We hope you’ve enjoyed your visit to Egyptian Mummies: Exploring Ancient Lives.

If you’re eager to spend more time with this history, please visit the ROM’s own

Egyptian galleries and the Mummy Portrait display, which are both located on the

3rd floor.

Partners & Sponsors

The presentation of this exhibition is a collaboration between the British Museum and the Royal Ontario Museum.