VIKINGS

The Exhibition

Date

About

Bloodthirsty plunderers. Pillaging warriors. Seafaring traders. What do we really know about Vikings?

Explore the myths and stereotypes of this ancient culture in VIKINGS: The Exhibition, presented by investment dealer Raymond James Ltd. Offering a fresh and contemporary look into the Viking Age, VIKINGS is an extraordinary window into the lifestyle, religion, and daily lives of these legendary explorers, artisans, and craftspeople. Encounter objects rarely displayed outside of Scandinavia in this compelling exhibition that challenges the perceptions of the Viking Age through hundreds of objects, as well as interactives, and immersive experiences.

Highlights

Vikings in Canada

Travel back in time over 1,000 years and explore the Viking footprint in Canada. Exclusive to the ROM, this section of the exhibition dives into the archaeology and history of the Norse on our East Coast. Follow their journey across the Atlantic and discover some of the myths and mysteries of these ancient peoples.

Descriptive Audio Tour

Download the playlist in advance.

Descriptive Audio Tour

Vikings: The Exhibition presented by Raymond James Ltd.

November 4, 2017 to April 2, 2017

STOP 1. WELCOME

Welcome to the Royal Ontario Museum.

Vikings: The Exhibition presented by Raymond James Ltd. Is an interactive exhibition featuring a

selection of archaeological finds from the Swedish History Museum in Stockholm, Sweden.

The exhibition is divided into nine themed sections. In this described audio guide you will find an

introduction to each one of these sections, commentaries about the most important objects and also

a few surprises.

Especially for this Toronto showing, the ROM has also added a section on “Vikings in Canada” –

an important facet of Viking history that we hope will truly resonate with our visitors.

For more than 300 years (approximately between the 8th and 11th centuries), seas and rivers were the

Vikings’ main allies. Setting sail from Scandinavia (now Sweden, Norway and Denmark), their ships

travelled across Europe from the cold Northern lands to the warm Mediterranean coasts, through the

great rivers far of the East and westward over the sea to the North American coast.

STOP 2. MEET THE VIKINGS

Who exactly were the Vikings? Were they actually called “Vikings”?

The first thing to know is that the Vikings were neither a people nor a nation. In reality, there were no

actual “Vikings”, but individuals from northern Europe (the Norse) who from time to time “went a‐

Viking”. “Going a‐Viking” meant setting sail and traveling far from home, sometimes to trade

peacefully, other times to rob and pillage and on other occasions to colonize territory. The aim of the

voyage was not always clear when they set sail.

If you wish to listen to a commentary on the objects displayed in this section, find number 2.1.

Otherwise you can continue exploring the exhibition.

STOP 2.1. OBJECTS: THOR’S HAMMER, BROOCHES AND OBJECTS FROM AFAR

No one was born Viking nor went a‐Viking throughout their life. This explains how some of these men

and women from the north had time to make the jewellery in the display cases here.

In this first display case (“Mythical animals and birds of prey”) you will see a small silver pendant in

the shape of an inverted T. It represents the god Thor’s most famous weapon, the Mióllnir hammer.

According to Nordic mythology, the Mióllnir never missed its target. What’s more, the hammer

returned of its own accord into Thor’s hands. The shape of the Mióllnir hammer is as representative

of Norse culture as the silhouette of a Viking ship.

The pendant itself bares Thor’s angry visage. The head of the pendant is wide, representing his

strong forehead and fiercely‐set brow. It’s framed by swirls of hair etched around the perimeter. The

piece then narrows to frame Thor’s nose and lips ‐ which appear to be agape in a thunderous roar.

The bottom of the piece widens again into a hard, square jawline ‐ engraved with large swirls

representing the hair of a long, pointed beard.

In another case (“Costume brooches reveal the differences in fashion”) on the same table you will see

six brooches worn by women. These brooches are fashioned out of bronze, silver and gold. Some

women wore two brooches on their chest linked by coloured half necklaces. The one featured here is

a string of glass beads ‐ in shades of green, red and gold ‐ on a fine silver wire. These brooches came

in a variety of shapes, including animal heads.

In a third display case (“Cultural influences”) there are two cowrie shells. One is pearl in colour and

features a comb‐toothed edge and resembles a hair accessory. The other is more mottled in texture

and colour, resembling an aged stone that’s almost split in half or a claw, as the shell is open down

the centre. These shells were sometimes worn as pendants and are the result of the import of luxury

goods. Cowrie shells are often found in the Red Sea and Indian Ocean.

Although some aristocratic graves contain bowls or plates of bronze, the bronze‐ladle in this case is a

unique object and very well preserved. It has subtle decorations around the perimeter and on the

underside of the handle, and is believed to have been used in ceremonies in the Coptic church of

Eastern Egypt.

In a while we will invite you to listen to a myth involving the god Thor. Don’t miss it.

In the meantime, continue exploring the exhibition.

STOP 3. FAMILY AND COMMUNITY

The modest tools, used for weaving and cultivating the earth, tell us a lot about what Vikings did

much of the time.

Medieval Scandinavia was primarily rural and archaeological finds show that men and women had

distinct roles. Women tended to the household economy and chores while men worked the fields.

Men, as well as many women, would occasionally take part in Viking expeditions ‐ but most never

left the place they were born.

More than gender or status, a person’s life was defined by if they were free. As with many societies

at that time, the Norse practiced slavery. Many were captured in the spoils of war; others were

common folk stripped of freedom for one reason or another.

For further commentary on the objects in this section, visit number 3.1.

STOP 3.1. KEYS FOR THE LADY OF THE HOUSE

The objects in this display case were found in female graves.

The first item, a horn, was used as a drinking vessel. The white [bull] bone tapers from its opening to

end in a point with delicate silver metalwork adorning the opening’s rim.

The second case contains the “Keys for the lady of the house”: a set of bronze keys in varying size and

shape. Whether functional or symbolic, keys indicated property, and the presence of them jingling in

a pocket represented power. Rather than pockets, Norse women would wear chains on their clothes,

from which they’d hang keys and household tools. Sometimes, a leather pouch attached to a belt was

used to display belongings that represented status.

In the same case there is also a silver pendant in the shape of a female figure in profile. It is thought

to represent a Valkyrie: the mythological character popularized by Richard Wagner’s opera. Valkyries

rode among warriors on the battlefield and chose the bravest to fight for the gods upon their death.

A second silver pendant ‐ this one a copy ‐ is crafted in the shape of a bowler chair. Known as the seat

of honour, it symbolizes women as head‐of‐the house and farm. It has a wide round base with no legs,

so as to sit directly on the floor. It features no arms and a low, arched backrest so as to be easily slip

in and out of. A pattern of silver studs likely represents a delicate fabric.

If you want to listen to a commentary about a warrior’s grave, find number 3.2. If not, you can continue

exploring the exhibition.

STOP 3.2. THE WARRIOR IN BIRKA

In this display case are finds from a Viking warrior’s grave, including a double‐edged iron sword. Most

remarkably, recent genetic testing suggested that the human skeletal material thought to be

associated with this grave was from a female, presenting the possibility that not all Viking warriors

were male... A possibility that is still the subject of much debate among the archaeological community,

mostly because there are still questions over the actual connection between the female skeleton and

the weaponry; could the skeleton have come from a different grave?

The grave was excavated close to Stockholm, in Birka, which is now a World Heritage site. The port of

Birka an important trading centre. . Birka also held a regional assembly, known as a ting. Only free

men could take part in assemblies. Because of Birka’s strategic importance it also had a military

garrison. Perhaps our anonymous warrior was part of it.

The iron stirrups displayed in this case are rudimentary in design, with a simple bar for a boot rest and

a ring at the top for strapping to the saddle. Their presence in a grave remind us that warriors were

sometimes buried with their horse, if they had one.

Continue exploring the exhibition.

STOP 4. HOMES, COLOURFUL AND BUSTLING

The heart of Norse society was the family. Most families lived on farms. Depending on the available

resources, farms would group together to form villages. Norse identity was forged by family and farm.

When asked “where are you from?” a Norseman or woman would probably respond with the name

of their homestead.

The wealthiest estates boasted a special building called the longhouse. Longhouses were long wooden

structures where sometimes banquets were held.

During banquets the Norse had lots of food, recited poetry, played music and danced. Although some

Norse instruments have been found, we don’t know what the music they played was like. Possibly the

closest we come nowadays is the traditional melodies and rhythms of Iceland and the Faroe Isles in

the North Atlantic.

If you want to know more about the Norse (how big they were, how they dressed) visit number 4.1.

Otherwise, continue exploring the exhibition.

STOP 4.1. LOOKING GOOD

The question “what were Norsemen and women like?” is inseparable from the question “how do we

know?”

One way to find out is to go to written sources. A contemporary Arab traveller described Vikings as

men who were as tall as palm trees, with beautiful bodies, pale skin and many tattoos.

This display called, Looking Good, features the skull of a Viking man. In addition to clothes and

jewellery, Vikings sometimes modified their bodies in different ways, like filing down their teeth. On

the upper jaw of this specimen, the front teeth show furrows created by deliberate filing. The reason

behind the strange dental practice is unknown but it seems to have been exclusive to men.

Archaeological finds confirm an average height of 5 feet, seven inches for men, only four‐and‐a‐half

inches below the average height of modern Scandinavian men. But human remains also tell us that

the Norse people suffered from illnesses and serious injuries, that they didn’t always have enough to

eat and that their lives were very hard, to the point that the majority of men died before they were

45. Women, who also faced the dangers of childbirth, often didn’t reach 30.

If we want to know how Norse folk dressed, we need to look at their graves. As well as remains of

fabric (wool in particular) we can learn from the tombs where exactly jewels were worn. While the

fabric may have decomposed we can discover, for example, where they wore brooches.

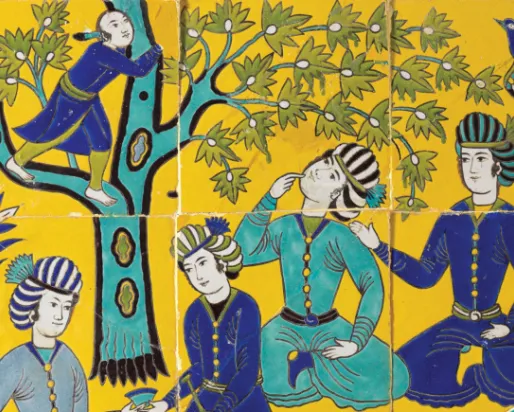

Another source of information about clothing is the artistic representations of the human figure found

on wall hangings, drawn on stone, and engraved in metal.

As for colours, there was the option of dyeing cloth. Dyes were obtained from plants. Yellow was the

easiest. Blue was more difficult and without blue you can’t get green. Red had to be obtained from

warmer latitudes and, therefore, not everyone could afford it. Not everyone could afford linen, silk or

gold and silver embroidery either. As in every other era, clothing was a symbol of social status.

We still have to look at another important question: What language did the Norse speak?

STOP 4.2. EVERYDAY RUNES

The Norse of the Viking era spoke Old Norse, the language from which Swedish, Norwegian, Danish

and Icelandic are derived. The alphabet they used, which already existed before the Viking age, is what

you can see in this part of the exhibition. If you look closely, you will notice that some of the letters

are the same as ours. Take the letter resembling our letter B, for example. (PAUSE) It was also

pronounced “B”. Other letters are not the same although they appear to be. Look for an arrow

pointing upwards. (PAUSE) It looks like our letter T, doesn’t it? It was also pronounced “t”. On the

other hand, other letters are completely different. Can you see a find a cross with a diagonal horizontal

bar? (PAUSE) The sound it made was N but it doesn’t look anything like our letter N. In any case, most

specialists believe that the Norse’s alphabet derived from the Latin alphabet. Though it wasn’t called

alphabet but futhark. The word futhark is made up of the first six letters of the Norse alphabet. In

fact, they weren’t called letters either, but runes.

Runes don’t have round shapes because they were engraved on hard surfaces. It’s not easy to make

the letter O with a hammer! And speaking of hammers, after the silhouette of the Viking boat and the

Mióllnir, (Thor’s hammer) runes are the other great icon of the Viking era.

Try writing your name in runes before continuing with the exhibition.

STOP 5. MORE THAN WORSHIP

An important role within the Old Norse (pre‐Christian) cult practice was played by amulets. With them

you were able to create a closer relationship to the gods that perhaps was more private and secret.

The amulets often have the shape of certain gods attributes. They occur in materials such as simple

iron but also in more exclusive materials such as amber or silver. Fire steel shaped rings are believed

to represent Freyr ‐ a god of fertility and prosperity, staffs and spears for the chief god Odin, and the

axe might represent Thor, the god of thunder.

Christians believe in a single God. On the other hand, the Norse who still practiced their ancestral

religion were polytheists. They believed in a considerable number of gods, goddesses and other

supernatural beings.

There were two main groups of divinities: the Vanir and the Aesir. The Vanir group was made up of

Njord and his two children. Njord is the god of the wind, fertile land, navigation and fishing. His son

and daughter, Freyr and Freyja, are the gods of fertility. With these characteristics, it’s not surprising

that the Vanir were the gods most venerated by the people, along with Thor.

Among the Aesir, we find Odin, the god of war and wisdom, his wife Frigg and his children. Thor, was

one of Odin’s children.

There were also the Norns, female figures who controlled destiny.

The 300 years that span the Viking Age began when Christianity was already established in Europe and

ended with an officially Christianized Scandinavia. Among the Norse of that time, some practised the

old religion, some were Christian and some probably practised both.

As the centuries went by, the cross began to substitute the symbols of Nordic religion. However, many

people, without realizing, still pronounce the names of the ancient gods every day. For example, the

third largest city in Denmark is called Odense, meaning Odin’s sanctuary. The capital of the Faroe Isles

is called Tórshavn, Thor’s port. And when we spend the week looking forward to Friday, we are

looking forward to the day of Frigg, or possibly Freyja.

If you wish to examine in detail some of the objects exhibited in this section, find number 5.1.

Otherwise, continue exploring the exhibition.

STOP 5.1. THE VANIR – GODS OF THE PEOPLE

The pieces in this display case (“The Vanir – Gods of the People”) are related to two of the Vanir gods:

Freyr and Freyja. It is thought that the phallic bronze figurine with an elongated torso and pointed

head represents the god Freyr, whom Norsemen associated with prosperity.

The silver pendant is a representation of Freyr’s sister, Freyja, the goddess of fertility. We can tell that

Freyja is pregnant and that she is wearing a brooch and a necklace like the ones in the display case.

This may portray Freyja with her magical gold jewel called Brisingamen.

If you want to explore another display case, find number 5.2.

STOP 5.2. DEAR ON BROOCHES TELL of CHRIST

Find the round, rather flat, silver brooch exhibited in this display case. It features four sculpted deer

standing at right angles. (PAUSE) The animals are gathered around a source of water with their heads

turned back.

The scene might be connected to these lines from the Book of Psalms in the Bible:

As the hart panteth after the water brooks,

So panteth my soul after thee, O God.

“Hart” is an old word for deer, and we know deer were used as symbols of Christ from the early times

of the Christian Church. The source of water could represent “the well of life” mentioned in another

psalm. Or it could also refer to Paradise, if we see it as a mountain with four rivers flowing from it. This

is how it is described in the Book of Genesis:

And a river went out of Eden to water the garden; and from thence it was parted, and became into

four heads.

The deer motif also appears, in a simplified version, on a number of silver box‐brooches, such as the

one displayed. Christian symbolism is not so evident here, particularly as they also convey other Old

Norse motifs.

Continue exploring the exhibition.

STOP 5.3. THE PANTHEON ACCORDING TO NORDIC SAGAS

Do you know those days when it rains and then the sun suddenly peeps out from behind the clouds?

On days like that, you’ll see the Rainbow Bridge that leads up to Asgård.

That’s where the gods live, high up among the clouds and the rustling leaves.

The giants and trolls live in Utgård and can be very frightening and dangerous. But the most dangerous

creature of all is the Midgård Serpent.

The geography of Norse mythology is complicated. To begin with, there is the Tree of the World, an

ash called Yggdrasil. Everything that exists in the cosmos exists in the space between the roots and

the highest branches of Yggdrasil. The Nornes, the weavers of destiny, live at the foot of the Tree of

the World. They are called Urdr (the past), Verdandi (the present) and Skuld (the future).

Asgård is at the top of the tree. This is the upper world governed by Odin where the gods have their

palaces. Midgård is Middle Earth where humans live. Asgård and Midgård are united by the bridge

Bifrost which the gods built out of water, air and fire and which only they can cross.

The giants, who are neither men nor gods, live in Jotunheim, site of the citadel of Utgård.

The elves live in Alfheim.

Altogether there are nine different worlds, all between the roots and the highest branches of

Yggdrasil. Odin was suspended from one of these branches for nine days and nine nights in exchange

for learning the secret of the runes. It’s not clear if this was before or after he gave an eye in order to

obtain wisdom. Yes, an eye! Ouch!

So, it’s time to get to know better the inhabitants of some of these nine worlds in Norse mythology.

We recommend that you begin with Thor, a god with a bit of a temper!

To listen to one of his adventures have a seat at one of the listening stations, or enter number 100 as

you walk. After that, or later on, you can listen to two more stories. They all have numbers that are

easy to remember: 100, 200 and 300.

STOP 6. THE LIVING AND THE DEAD

Before the arrival of Christianity, Norsemen buried their dead close to the family farm, sometimes

under a small pile of earth or tumulus. Often, though not always, they were cremated before they

were buried. In time, Christianity unified funeral customs. The Norse stopped cremating the dead and

began to bury them in local cemeteries next to the church. Gradually, the dead ceased to belong to

one family alone and belonged to the Christian community in general.

The objects and animals buried with Norse men and women, whether they were cremated or not, give

us clues into their beliefs. Spiked shoes, for example, were possibly meant for the dead to walk with

on the icy path that led to Hel, the kingdom of the dead. Horses, carts and sledges could also make

the journey easier. The dogs were perhaps there to guide them on this one‐way journey.

But the Norse’s most remarkable burial custom was to be buried or cremated within a ship. To be

buried like this must have been a great honour because a ship was a most valued possession. In fact,

it seems that at times, in order not to waste resources, just the nails were buried instead of the entire

ship.

STOP 6.1 THE GHOST SHIP

This hanging sculpture is composed of the 219 iron rivets of an authentic Viking ship, from eastern

Sweden. The ship’s planks, boards, oars, etc. long ago decomposed – leaving only the rivets in the

ground where it was buried. Here, the rivets have suspended from almost undetectable wires, in the

shape they were discovered ‐ showing the ghostly, three‐dimensional silhouette of the original

vessel.

Continue to explore the exhibition.

STOP 7. NORSE CRAFTMANSHIP

Norse men and women liked beautiful things. We know this because, although their life was far from

easy, they clearly owned jewellery and other luxury items; some of them made from material as fragile

as glass. But we mostly know they liked beautiful things because they made ordinary objects ‐ such as

swords, bridles for horses, combs for weaving and utensils for ironing clothes ‐ into things of beauty.

In this section the Norse’s skill in working the materials at their disposal: wood, leather, clay, bone,

horns, fabric and, especially, metal, are on full display. In the cases you’ll find some of these raw

materials and many of the tools that artisans used.

It is believed that among these tools there were some primitive magnifying glasses: round pieces made

of glass. The Scandinavian climate meant people couldn’t work outdoors all year round and houses

hardly had any windows, so it’s not surprising that artisans used magnifying glasses to work.

While you’re exploring the display cases in this section, consider the shapes used for decorating the

more elaborate pieces. At first they seem like simple geometric shapes but upon closer inspection you

will find that many of them represent real and imaginary animals. This style of decoration was deeply

rooted in Scandinavia: it existed before the Viking age and survived into the Christian era.

STOP 7.1 EXQUISITE ARTS AND CRAFTS

The so‐called Penannular brooch on display is made of silver and bronze and gilded. The circular

brooch features an animal face at the top centre. The circle remains open at the base and an animal‐

head with its teeth bared crowns each end‐knob. Fine filigree inlays of gold make this brooch even

more spectacular. Brooches were an important and common accessory in the Viking Age, used not

only for practical purposes but they also served as indications for rank and social position. They were

often decorated with animal‐heads on the end‐knobs, although Penannular brooches with this

splendid design and size are quite unusual.

Go towards the sword in this section and select number 7.2.

STOP 7.2. THE SWORD

This sword is a harmless replica of the kind used by the Norse. When you lift it, consider how long you

could carry it on your back or hanging from a belt. Would you be able to hold it in one hand like the

Vikings did? I do hope so, because otherwise you wouldn’t have a free hand to hold your shield!

The sword was the most prestigious weapon among the Vikings. We will talk about it in the next

section.

STOP 8. AWAY ON BUSINESS

Weights and scales found in tombs tell us that the Norse engaged in commerce. But what did they

sell?

To begin with, they had a lot of woodland. This gave them access to timber, honey, wax, horns,

amber and animal pelts. Vikings also produced flint, tar and iron, and trafficked slaves.

And what did the Norse seek when they would go a‐Viking? Top of the list was silver, for everything

from jewellery ‐ as displayed here ‐ to currency. In those days, one might carry “money” by way of a

silver bracelet that would be divvied into chunks to pay for things ‐ hence the scales.

Silver coins, jewels, rods and bars flowed in the Viking Age ‐ much of it from plundering and much of

it from trade. Some was also buried for safekeeping and many Viking silver hoards likely remain buried

to this day.

STOP 8.1. PRESTIGIOUS WEAPONS

In this area you can see real swords, the head of a battle axe and the point of a spear. Along with bows

and arrows, these were the weapons Norsemen used when they left their homes to go a‐Viking.

They’ve rusted with time but were once shiny, and certainly ‐ sharp, metal. The non‐metal elements

like the pole of the axe and handle of the sword have long disintegrated.

The best swords, and especially the blades of these, were imported from the continent. An inscription

on the long needle‐point blade of this particular sword states that it was made by the sword smith

Ulfberth (or a sword smith‐“company” with the same name) which probably was located in present‐

day Germany.

In ideal battle conditions the first weapon used would have been the bow and arrow. When the enemy

drew closer, Vikings would have used spears, and in hand‐to‐hand fighting, axes, swords and even

knives. In ideal conditions, warriors would have had some protective elements such as leather or metal

helmets, some sort of chain mail garments and, above all, wooden shields (with a shield‐boss, i.e. a

metal piece in the middle to protect the hand). Battle axes, such as the on display in this section, often

had a hook. Why? Well, with this hook it was possible to catch hold of the enemy’s shield and pull it

aside, making them more vulnerable.

However, we don’t know how often the Vikings fought in ideal conditions. Very possibly their battle

axes were often the same ones that they would have used on the farm. Very few would have had a

sword and fewer still a sword with a decorative handle and a double edge reinforced with steel. Metal

helmets and chain mail were very special accessories.

In reality, the Vikings’ best arms were bravery, their ships and… the element of surprise.

STOP 9. OVER THE SEA

Ever since the first replica of a Viking ship crossed the Atlantic 125 years ago, history and sailing fans

have been able to see dozens of functioning reproductions of Norse ships, each one more exact than

the one before. These reproductions have been built using data collected in various ways. On the one

hand, gathering details from the remains of real ships studied by archaeologists and other experts.

But also from visual information found on picture stones or on the famous medieval tapestry of

Bayeux in Normandy. Written sources and clues from ancient local traditions were also taken into

account.

Norsemen perfected ship design, and each Viking ship had a different function:

Smaller boats were used for quick coastal excursions or river jaunts to the Baltic Sea.

Merchant ships were slow but able to carry large cargo, which helped when colonizing new territory.

But the outline that was feared the most, and the one that still comes to mind when we think of the

Vikings, is the longship silhouette. The Viking longship was the perfect warship: strong, light, fast and

easy to manoeuvre. It could go under sail in open waters but it was the strength of its oarsmen that

allowed it to appear and disappear like a ghost during battle. Narrow enough to enter almost any river,

it didn’t need more than a metre of water below the keel and was so flat that it didn’t need a port to

moor: it could be dragged ashore like a small boat. Nor did a longship need to turn round in order to

retreat because it could be rowed in reverse. It was also so light that it could be taken out of the water

and sometimes carried across land. And although it was light, it wasn’t fragile. Each plank, cut with an

axe so as not to break the grain of the wood, was fixed to the plank immediately below it to make the

ship stronger and more waterproof. The oarsmen and the warriors were one and the same. They slept

on deck and sat on the trunks containing everything they needed for the voyage. All resources,

including space, were stretched to the maximum. The sail, made of wool and smeared with animal fat,

could cope with any kind of wind.

Dragon figureheads and blood‐coloured sails terrified people when they saw them but we don’t know

if this was their original function.

If you want to know how far the Norse travelled on these magnificent ships, visit number 9.1.

STOP 9.1. TRAVELLING EAST AND WEST

Between the 8th and 11th centuries the Norse set off on expeditions in all directions.

To the east, where there were few opportunities for pillage but many for trafficking in slaves, Vikings

sailed, or rowed up the Volga as far as the Middle East. They threatened Constantinople more than

once but the Byzantine emperors also chose them for their loyalty to join their Vareg guard. Vikings

settled in what is now Ukraine where they were actually called rus.

Heading south, they went upstream along the Seine and sacked Paris. In order to put an end to their

attacks, the Franks let the Vikings settle in the north of France (what is Normandy today). Christian

descendants of those Vikings founded a prosperous principality in southern Italy.

It might surprise you to learn that, for one entire week in the year 844, the Vikings sacked one of the

most important cities of the Cordoba caliphate, Isbiliya, the place we now know as Seville, Spain. They

arrived by going up the river Guadalquivir.

To the west, they repeatedly attacked the British Isles, with monasteries being one of their favourite

targets. We know, for example, that at the end of the 8th century they attacked a monastery in

northeast England, on the island of Lindisfarne. The foundation of Dublin is proof of their continued

presence in the area. The Vikings also colonized Iceland, which was then more or less uninhabited.

And as we’ll see later on, from Greenland they travelled as far as Canada .

STOP 9.2. REINTERPRETTING THE VIKINGS

In this part of the exhibition we look at some of the clichés associated with the Norse over the

centuries. We begin, naturally, with those famous, and non‐existent, horned helmets.

Archaeologists have found very few helmets from the Viking era and none with horns.

In fact, it seems that the mistaken notion of Vikings with horns comes from… opera! Specifically, the

costumes created for the premiere of the Ring of the Nibelung, the cycle of four operas written by

Richard Wagner in the second half of the 19th century. Who could’ve guessed that a prop devised by

Carl Emil Doepler, a set designer, would become much more famous than the designer himself?

However, it is much easier to forgive Mr. Doepler’s poetic licence than the Nazis’ attempt to

appropriate Viking iconography, when they borrowed runes to create the logo of their infamous SS

organization.

Fortunately, the rigorous work of archaeologists and historians made accessible by exhibitions such

as this one is setting the record straight. Researchers still don’t have the answer to all our questions

about the Norsemen but their work continues. For example only a small percentage of the important

archaeological site in Birka, Sweden, has been excavated.

Meanwhile, you can continue to enjoy the greatest treasure they have left us – their incredible stories.

STOP 10. VIKINGS IN CANADA

In the early 11th century, Vikings arrived in Newfoundland and established a small encampment –

known today as L’Anse aux Meadows. The Sagas, written two hundred years or more later, recount

multiple Norse explorations to present‐day Canada. Taken together, the archaeological and written

records of Canada’s Viking history provide valuable information on the trials and tribulations of

settling and exploring what was yet another new frontier for the Norse.

Leif Eriksson was the first to intentionally explore this new territory. His expedition delighted in the

rich natural resources that they found, including salmon, timber, and even wild grapes. The latter

inspired them to call this place Vinland (or “wine land”).

STOP 10.1. L’ANSE AUX MEADOWS

In 1961, Norwegian explorer Helge Ingstad announced an important find – traces of a small, very old

encampment at L’Anse aux Meadows in Newfoundland. Years later, this remains the only firm

archaeological evidence for a Norse presence in Canada. The site consists of the footprints of eight

main structures, visible above the ground as a series of grassy ridges. Initial archaeological

excavations by Anne Stine Ingstad showed it was occupied by the Norse just over 1,000 years ago.

It is possible that this site was built and occupied by Leif Eriksson and members of his expedition.

Each hall area at L’Anse aux Meadows was likely a manor – with a large communal living area used

by residents and a private living area reserved for the head of the manor, his family, and close

associates. Some of the smallest huts may represent slave dwellings. This display case features a

bronze pin, not quite 5 cms in length. With a straight barrel that has no key‐like teeth, and only a

simple ring at the head this object would have been used for fastening a neck cloak. It is also one of

the first Viking artefacts found at L’Anse aux Meadow ‐ which remains the only firm archaeological

evidence of Norse presence in Canada.

STOP 10.2. INDIGENOUS‐NORSE INTERACTION

When exploring Canada, the Norse encountered Indigenous peoples – they called them skraelings (a

term they also applied to the indigenous peoples of Greenland). The Sagas include descriptions of

both friendly and violent encounters.

In this display, you is a small small stone crucible (a tool used in metalwork), excavated from an

archaeological site on Baffin Island. , excavated from an archaeological site on Baffin Island. Though

it looks like a standard rock, scientists found traces of a copper‐tin alloy and glass spherules on the

inside of it; hinting that it was once used at high‐temperatures to tool non‐iron metalwork. Such

technology was previously unknown in the area before Europeans arrived. Given the location of this

find, it is possible that the crucible relates to Norse‐Indigenous interaction in the far north.

LISTEN TO VIKING MYTHS

STOP 100. THOR TAKES A BITE

There are lots of stories about Thor’s adventures. Lots of people have told them, each in their own

way. This is the story of how Thor went fishing. Like all fishermen’s tales, it changes a little bit with

each telling.

Thor is the god of thunder. He’s the one who makes all the thunder and lightning, as he drives his

goat‐driven chariot across the sky and wields his mighty hammer.

But sometimes, Thor gets a bit tired of making thunderstorms. He longs for adventure. He'd rather

fight giants and trolls.

The giants and trolls live in Utgård and can be very frightening and dangerous. But the most dangerous

creature of all is the Midgård Serpent, the Serpent of the World. Thor would really love to come face

to face with it.

In fact, when the Midgård Serpent was little, it lived in Asgård with the gods. But the gods got tired of

tripping over the small slippery snake. (They didn’t like the way it stared at them either. It didn’t look

very friendly, you know.) And that's why Odin, who is in charge of Asgård, threw the serpent into the

sea, so the gods wouldn’t have to look at it ever again.

Now the Midgård Serpent lies at the bottom of the sea, and it isn’t that small any more. It has grown

so big and so long that it encircles the whole world! And it's angry as well. It lies down there, biting its

tail, and thinking how best to take revenge on the gods.

Thor often boasts that one day he'll go fishing and catch the terrible Midgård Serpent.

“We know you fight giants and trolls”, say the gods. “But how are you going to fight a serpent that’s

as big as the whole world?”

“No problem”, says Thor. “I’ve got my hammer Miollnir and my belt of strength.”

When Thor tightens his belt of strength, it makes him twice as strong.

“Yes, yes”, say the gods, “of course you will”.

“I’ll show them I can catch the Midgård Serpent”, thinks Thor.

But first, he needs a boat. Then he remembers the giant Hymir who lives by the sea in Utgård: he has

a good, sturdy boat. Thor decides to pay him a visit.

But before setting out, he disguises himself as a little boy so the giant won’t recognize him. That's

really clever of him. The giants don’t like Thor very much, after all the times he’s travelled to Utgård

to fight them. When Thor arrives in Utgård, he finds Hymir down by the beach, getting his boat ready.

“What are you doing?” asks Thor in his best little boy’s voice.

Hymir glares at the boy.

"Mm. That red hair looks familiar." But the giant has no idea this little chap is really Thor.

“I’m going fishing,” he says grumpily.

“Can I come, too?” pleads Thor.

“You’re too small”, thunders Hymir. “I’m not taking small boys on my boat. It's too cold!”

“I’ve got warm clothes on”, says Thor, patting his woolen shirt. (His hammer and his belt of strength

are well hidden underneath it.) The giant nods crossly.

“Hm. Alright then” he mutters. “But you’ll have to bring your own bait.” He points to a field nearby.

“You’ll find plenty of worms over there.”

Thor dashes off to the field. But worms won’t be enough for the kind of catch he has in mind. He’s

going to need something much, much bigger. So he goes up to one of Hymir’s prized bulls and swiftly

twists its head off. Hymir goes pale when he sees the little boy coming back with a bloody bulls head

under his arm. He’s never encountered a boy quite like this one before.

Thor and the giant get into the boat. As Thor places the bull’s head by his feet. Hymir stares at him

grimly. That was his best bull! But Thor doesn’t even notice that Hymir is angry. He grabs the oars and

rows out to sea at top speed. The giant watches him quietly, and once the boat is far enough from the

shore, he clears his throat and says:

“Let's stop here for a while. This is where I usually fish for herrings.”

“Ha! Small fish!,” snorts Thor and carries on rowing with powerful strokes. The giant looks at the boy.

There’s definitely something familiar about him, but he can’t quite figure what.

The water gets darker, and land is soon out of sight. Not even birds dare come this far from the shore.

Hymir sits grunting with his head in his hands. They have entered the realm of the Midgård Serpent,

and the giant knows this is no place for them to be. Thor lifts his oars with a satisfied sigh. This is going

to be his best adventure ever!

Thor chooses a fishing line that is as thick as his thigh, and fastens the bull's head to the hook. He

throws out the bait, which disappears in the water with a mighty splash.

“Aren’t you going to wish me luck?” Thor asks. Beads of sweat appear on the giant’s forehead.

“Watch out, boy. You might catch a bigger fish than you bargained for,” says Hymir in a worried voice.

The giant just wants to go home, away from these treacherous waters. He wishes he had never set

eyes on this little boy. Meanwhile, the Midgård Serpent lies in a coil at the bottom of the sea, biting

its tail dreamily. He likes to imagine how, one day, he will destroy those gods who threw him into the

sea. And it’s not just the gods he wants to bite. The Midgård Serpent dreams of destroying the whole

world, and Utgård, too.

Suddenly something bumps against the serpent’s nose. It's the bull’s head on the hook. The Midgård

serpent spits out his tail and swallows the head, hook and all.

A huge wave surges over the sea and jolts the boat. Hymir clings onto the gunwale with both hands.

Thor loses his balance for a moment, and grips the line tightly.

“We’ve got a bite”, he whispers to the giant.

When the Midgård serpent realizes he’s been caught, he starts lashing out with his tail. The sea churns,

the sky turns black, the giant throws himself to the bottom of the boat. On the shore, mountains shake

and wolves howl with fear. The whole world shakes as Thor struggles to pull the Midgård Serpent out

of the depths of the sea. Reaching under his shirt Thor tightens his belt of strength. Now he is twice

as strong. He pulls and pulls so hard that his feet push right through the bottom of the boat. Then,

with a final haul, he drags the serpent out of the water.

Thor and Hymir shiver as they stare straight into the eyes of the mighty beast. The gaze of the Midgård

Serpent is cold. He has a scaly head with long feelers. His slippery body twists and turns as he hisses

and spits out his foul‐smelling venom. Thor takes out his hammer, and just as he is about to fling it on

the serpent's head, the giant springs to action. Hymir pulls out his knife and cuts the fishing line

throwing Thor backwards into the boat. The Midgård Serpent is free again. He blinks a few times

before sinking back down into the sea with the line still hanging out of his mouth.

The sea is calm again. The mountains stop shaking, the sky is clear. Everything is back to normal. It

almost feels as if nothing had happened.

“Nooo!!!” shouts Thor as he boxes the giant's ears. “No one will believe me now!”

Angry as a hornet, Thor jumps out of the boat and wades back to shore. Hymir rows his way back. That

night, the giant can’t sleep. He keeps thinking about the strange red‐haired boy and the terrible

Midgård Serpent. It’ll be a long time before he goes fishing again.

Thor goes home to Asgård where he tells everyone how close he came to catching the Midgård

Serpent. He describes the serpent’s terrifying eyes. He stretches out his arms to show how large it

was.

”It was this big!” he boasts.

Thor vows that one day he will try to catch the serpent again. One day, he will succeed. One day,

before the days of the gods and giants come to an end.

STOP 200. THE APPLES OF IDUN

This story is a thousand years old, maybe even older. It’s been told by lots of different people in lots

of different ways. It’s been told so many times that nobody knows any more how the original story

went.

Right at the very top of the World Tree is a kingdom called Asgård. That’s where the gods live, high up

among the clouds and the rustling leaves. If you’ve been there, you’ll know that the gods are young

and strong, even if they’re as old as the hills. Their hair doesn’t go grey, and they don’t get wrinkles or

get weaker with age, like us humans do. Years come and go ‐ a hundred, a thousand years – but the

gods stay young forever. And do you know why? Well, it’s all thanks to Idun.

Idun is a goddess. Wherever she goes, she carries with her a beautiful little box that she never puts

down. That box contains the most valuable thing in the world: Idun’s apples. The apples are golden

and shiny, they‘re juicy and thirst‐quenching. They’re the most delicious apples there have ever been.

But the really amazing thing about these golden apples is not how wonderful they taste. It’s their

magic powers. Those who eat them never grow old.

Idun guards her apples carefully. None of the gods’ children can have so much as a bite, and none of

the gods are allowed to eat too many. That’s because the more apples you eat, the younger you get.

So Idun must be very strict. The gods are allowed one apple a day, no more no less. When Idun gives

someone an apple, a new one immediately appears in her box. It’s magic. (Magic is quite common in

the world of gods, you see).

But it’s not only the gods who live in the World Tree. In the lower branches, far away from Asgård, lies

Utgård, the land of the giants. The giants would love to get hold of Idun’s apples. They want to be

young and strong forever, too, just like the gods. But Idun says no. Only the gods are allowed to eat

her apples.

One of the giants, whose name is Thjazi, is always wondering how he can steal Idun’s apples. One day,

he sees his chance. It all starts when he has an argument with Loki. Loki is a giant, too, but he looks

like a god and actually lives in Asgård. Loki is constantly getting into arguments and fights. And most

of the time the gods just try to ignore his troublemaking.

However, this time Loki does something really stupid. To make up with Thjazi, he promises to lure Idun

away and hand the apples over to him. Loki regrets it almost immediately, but a promise is a promise,

and he has to keep his word.

The first problem is getting Idun to leave Asgård, which she never does. Loki goes to Idun and tells her

that in a large forest outside Asgård, he has seen a tree with golden fruit. He tries to convince her to

follow him into the forest.

“Maybe the fruit of this tree has the same magical powers as your apples!”, says Loki.

Idun is finally persuaded. Side by side they leave Asgård and enter the vast forest.

Thjazi the giant is ready and waiting. He has disguised himself as an eagle and is circling high up in the

clouds. He follows Idun and Loki’s every move, waiting for the right moment to pounce. He dives down

towards Idun, the wind whistling through his wings. He grabs her and her box with his giant claws,

flaps his wings and soars up into the sky again. Idun screams and beats Thjazi until feathers fly.

Loki stays on the ground and watches them rising higher and higher. Soon, all he can see is a small

fluttering speck in the distance.

Idun is gone. The world stands still. For a long moment everything goes silent. Strange things start to

happen to the gods. At first, they don’t even notice. A grey hair in Thor’s beard, a tiny wrinkle between

Freya’s eyes… A freezing cold blast of wind blows through the top of the World Tree. Everything seems

a bit greyer, just a little bit sadder.

No one understands what’s gone wrong. Until the watchman at the gate remembers that he’d seen

Loki and Idun walking out of Asgård. And yes, he clearly remembers that Idun was carrying her box.

The gods put two and two together and start looking for Loki. By then one of the gods has backache,

another is going bald, a third is going deaf. Now that Idun is gone, they are all growing old, and fast.

When they finally find Loki, they’re fuming with anger. Loki breaks out in a cold sweat. Shaking with

fear, he promises he will fetch back both Idun and her apples. If Freya lends him her falcon disguise,

he’s more than willing to venture into Utgård. Freya fetches the disguise and lays it on the ground in

front of him.

Loki puts on the beak and wings and flaps away. It takes him a while to get the hang of flying, but soon

he’s floating high in the sky. He peers down over the World Tree and sees dark thickets and black

water. It is Utgård, the world of the giants.

He can see Thjazi’s farm but no sign of the giant. Loki’s beak feels dry, and his wings are tired. He

cannot keep on flying.

Loki manages to land and find Thjazi’s house. He pushes the door open and scrapes the floor with his

bird feet. There, in darkness, sits Idun. She’s holding the box in her arms, a few apple cores glistening

in the shadows. Loki reveals himself, and asks her to forgive him for what he did. Idun is angry. She

looks at his skinny bird legs and unsteady wings.

“Will you carry me back to Asgård in your beak?” Loki nods. “Then turn me into a hazelnut, but promise

you won’t swallow me on the way home” says Idun firmly.

Loki nods again and magically turns Idun and her box into a tiny brown nut. He picks her up in his beak

and flies up and away from Utgård. But Thjazi the giant comes back just in time to see them taking off.

He flings on his eagle disguise and flies off after Loki and Idun. He can fly faster than the wind.

In Asgård, the gods see Loki heading towards them, followed by a fierce‐looking eagle.

“Quickly, let’s build a fire”, one of the gods says.

And just as Loki reaches the ground and Thjazi is about to land, they light it. The hot flames whoosh

up and burn off the giant’s feathers. Before he knows, he’s crashing into the fire.

Loki takes off the falcon disguise and turns Idun back to her original shape. The gods stand silently

around the fire until there’s nothing left of Thjazi the giant.

“Oh, well”, says Idun finally, opening her box. “Anyone fancy an apple?

STOP 300. THE DEATH OF BALDER

Hullo! Yes! It’s you I’m talking to, sitting there under that tree. Let me tell you a story.

Do you know those days when it rains and then the sun suddenly peeps out from behind the clouds?

On days like that, if you look up at the sky, you’ll see the Rainbow Bridge that leads up to Asgård. Up

there, behind a wall, there are houses and farms. And that’s where the gods and goddesses live.

There are lots of gods. And they all have different powers. One of them is strong, another clever, one

can do magic, another knows everything there’s to know about love.

Apart from that, the gods are very much like us. They can get annoyed, bored, angry or jealous, just

like we do.

With one exception: Balder. Balder’s always kind, always cheerful. And he’s so good‐looking that gods,

humans and giants all fall in love with him the moment they set eyes on him. It’s no wonder: Balder

has such fair hair… And you should see his eyelashes; they’re just like white petals!

Anyway, let me get on with the story.

One morning, Balder isn’t feeling himself. He’s worried and depressed.

“Last night, I dreamt of my death”, he whispers.

All the gods worry; most of all, Balder’s mother, the goddess Frigg. She knows that sometimes the

dreams of gods come true.

“Don’t be afraid, my dear son”, says Frigg. “I’ll make sure that nothing bad can happen to you.”

The goddess takes her plea to the fire and the stars, to iron and water; to all animals and trees, to the

scariest giants and naughtiest trolls.

“Promise you’ll never harm Balder”.

And they all promise, because they all love him. That is, all except one: Loki.

Loki lives in Asgård, and he looks very much like a god, but he’s actually a giant. And just as everyone

loves Balder, hardly anyone likes Loki. Loki can do magic, and he’s not bad‐looking either, but he plays

too many tricks and mostly just causes trouble. That’s why the gods try to avoid him as much as they

can.

One day, Loki is sitting in the shadow of a tree in a meadow in Asgård. Next to him is the blind god

Hod, who has not joined in the gods’ newest pastime.

The gods are shooting arrows at Balder, knowing he cannot be harmed by iron or stones. The arrows

just bounce off him and tickle him until he chokes with laughter.

“Loki, what’s going on now?” asks Hod, hearing the gods clap and cheer.

“Now it’s Thor’s turn to shoot”, says Loki. “He’s taking aim.”

“Oh dear”, says Hod. “But it won’t be a problem for Balder, will it?“

“Nah, he won’t get so much as a scratch”, says Loki, sounding disappointed. “Thor might as well tickle

him with a feather.”

“Isn’t he the best?”, says Hod, impressed. “There’s nobody quite like Balder.”

“He’s not that great”, says Loki. I know plenty of people who are just as charming and good‐looking. ”

“Yeah, right. Like who?”, asks Hod.

The gods cheer again. One of the goddesses strokes Balder’s fair hair. Balder says something and

everyone around him laughs.

“I’ve had enough of this!“, says Loki, getting up. “Haven’t people in Asgård got anything better to do?”

“Don’t go”, says Hod. “You’ve got to tell me what they’re doing now!”

But Loki has already left. He’s gone into the forest so he doesn’t have to look at Balder for a while.

“Balder, Balder, Balder”, mutters Loki. “Nothing but Balder. I wish he would disappear for good.”

And then he remembers Frigg’s plea. Has she really talked to everyone and everything in the whole

world? Has she really got every living or dead being to promise never to harm Balder? Loki decides to

find out. Maybe she forgot something. Loki asks the big trees and the little trees, he asks the rose

bushes and the oak trees, the alders and the boles. But all the plants give him the same answer:

“I couldn’t harm Balder. He’s so handsome and good!”

But then Loki catches sight of a small plant with dark green leaves. The plant is called mistletoe, and

apparently, it hasn’t promised anything at all.

“Hm, I’ve never heard of this Balder”, grumbles the mistletoe. “Frigg never even spoke to me. She

probably thought I was too small!”

“Then come with me!”, says Loki, breaking off a small sprig of mistletoe.

He whittles it into an arrow and runs back to the meadow. Hod is still sitting under the tree and

listening to the gods cheering.

When Loki sees the blind god, he has a really wicked idea.

“I’ve got a bow and arrow for you”, says Loki. “Now you can join in the games, too!”

“ I’m not so sure”, says Hod. “I wouldn’t be able to hit anything!”

“Go on, have a go”, says Loki. “I’ll help you!”

Hod stands up reluctantly. Loki stands behind Hod and helps him pull back the arrow and take aim at

Balder. The mistletoe arrow flies up and over the field, but when it hits Balder’s naked chest, it doesn’t

bounce off and fall to the ground, like the other arrows. Instead, it plunges into his flesh and pierces

his heart, exactly as in Balder’s dream. The handsome god falls to the ground and dies, lying as white

as a flower in the green grass.

Out in the field, the gods fall silent. For a while no one dares utter a single word. When they finally try

to speak, the gods are choked with tears. Only Hod’s voice is heard.

“Eh, what’s happened? Loki! What’s going on?”

Loki has disappeared again. He plans to keep out of the way for a while, just until the memory of

Balder has faded.

But Loki was wrong when he thought Balder would one day be forgotten. The whole world cried when

the god lay dead in the meadow. The trees, even the stones, shed tears.

The story of Balder has been told over and over by different people at different times. With every

telling, Balder gets nicer and fairer and Loki nastier and nastier. How would YOU tell the story?

Partners & Sponsors

The exhibition is a joint venture between and produced by The Swedish History Museum in Sweden and MuseumsPartner in Austria.

Royal Exhibitions Circle:

Gail and Bob Farquharson, James and Louise Temerty, Richard Wernham and Julia West