Long Distance Interaction in the Ancient Andes

Categories

About the Project

The focus of Justin Jenning's fieldwork is on the impact of the Wari (AD 600 - 1000) and Inca (AD 1430 - 1532) states in the Cotahuasi, Majes, and Siguas Valleys of southern Peru.

Excavation at Quilcapampa, a Wari-influenced site in the Sihuas Valley, Peru (2015-2017)

Petroglyphs located just below Quilcapampa

Although our contemporary globalized world is in many ways unique, the history of many regions can be broken up into periods of regionalism followed by broad cultural horizons of shared art styles, technology, and religion. These cultural horizons were transformative eras associated with colonization, surging interregional interaction, and widespread social change. What caused these earlier cultural horizons is an enduring question in archaeology. While often linked to the expansions of early states, these polities were generally too weak to directly shape the lives of many of those living in far-off communities. People chose to radically reshape their lives during these periods. Why?

One example of a cultural horizon that has been linked to state expansion is Peru’s Middle Horizon Period (600-1000 AD), a period associated with the rise of the Wari state in the central highlands, the spread of a Wari-derived artistic style, and the construction of a group of peripheral sites occupied by settlers from the Wari heartland. Over the past two decades, Justin Jennings and his colleagues have sought to understand why people adopted Wari-inspired lifeways in the valleys of southern Peru. With funding generously provided by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council, National Geographic Society, Royal Ontario Museum, and the University of Toronto, Jennings is continuing his work on this theme through excavations at the site of Quilcapampa, a site the grew to regional prominence during the Middle Horizon.

Using a variety of techniques from drone photography to isotopic analysis, the Quilcapampa project will provide a better sense of how this site grew, the changes in lifeways of its occupants, and the role, if any, of the Wari state in the societal transformations that occurred in the period. Excavations begin in July 2015, and videos, photographs, tweets, and text will be posted as the work unfolds both during fieldwork and in the lab work that follows.

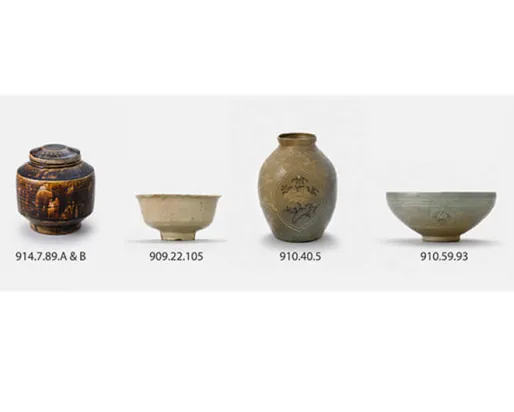

Analysis of Excavated Material from La Real, a Wari-influenced funerary complex in the Majes Valley, Peru (2009-2010)

A Wari-inspired pot from La Real

In the summer of 1995, a bulldozer operator extending a soccer field exposed two burial contexts in the village of La Real in southern Peru. Bystanders immediately rushed into the cave and rectangular structure to look for the mummy bundles that are commonly found in later period tombs on the arid coast of far southern Peru. Called pelotas—the Spanish term for balls—each of these bundles is usually composed of a tightly flexed individual that is often wrapped in multiple layers of textiles. Offerings were typically placed within the textiles or on the ground beside the mummy.

The villagers found a wealth of bones, cloth, ceramics, wood, and other material on the surface, but they were unable to discover any pelotas in the brief time before the La Real contexts were secured. The ensuing excavations of the site directed by Pablo de la Vera demonstrated that mummy bundles had been deposited at La Real. With its feathered textiles, face necked jars, engraved gourds, exotic animals, and precious metals, La Real was actually one of the richest tombs ever discovered in the region. Yet these bundles had been intentionally opened, and their contents broken, scattered, and often burned.

The destruction of the mummies was surprising. There is a long tradition in the Andes of keeping the individual intact after death since visiting with the deceased was often an integral part of ancestor worship. Archaeologists and locals were both accustomed to finding intact bundles in undisturbed burials in this region, and it was initially suspected that the mummies had been broken apart during colonial or modern looting.

Yet there was strong evidence to suggest that both the cave and the outlying structure had been untouched since they were sealed near the end of the Middle Horizon period (600-1000 AD). Moreover, the layering within the contexts suggested that the destruction was not a single act of desecration or rebellion, but rather a routine procedure that followed the burial of an individual. It did not make sense. Why would a group expend considerable effort to carefully prepare mummy bundles and then bring together a wide array of exotic and labor-intensive grave goods if the assemblage was ultimately destined to be destroyed?

An international research team was put together in 2009 to address this question. With the exception of human remains from La Real, the material from the 1995 excavations had been transferred to a storage facility and left unexamined for almost 15 years. Our team opened the boxes of La Real artifacts and analyzed the ceramics, textiles, metals, botanical remains, faunal remains, leather work, and spindle whorls that had been recovered from the site.

Based on this research, we argue that the destruction of the mummy bundles can perhaps be best explained as a reaction to a surge in long distant interactions that brought this part of Peru in contact with a variety of people, objects, and especially ideas that threatened the stability of centuries-old local traditions that celebrated relative equality. Newly won elite positions were initially legitimated through association with exotica, but were replaced by the end of the period by objects that signaled ties to a burgeoning regional economy. The objects that signaled these extra-local entanglements were celebrated as status markers at death, but were ultimately erased in subsequent mortuary ceremonies that broke apart, scattered, and burned the remains of elite individuals.

The results of this research have recently been published in Spanish in a volume entitled Wari en Arequipa? Análisis de los contextos funerarios de La Real (see list of publications if you are interested in downloading a free copy of this book). English language discussions of our findings are currently being written.

Excavations at Tenahaha, a Wari-influenced site in the Cotahuasi Valley, Peru (2004-2007)

Over the past 25 years, archaeologists have become increasingly aware of the complex nuances of culture contact and the difficulties in distinguishing between a broad range of interregional interactions based solely on the archaeological record. This situation is particularly relevant to the Middle Horizon (AD 600 - 1000) period of Peru, since writing only appeared in the Andes after the Spanish Conquest in 1532 AD.

Wari emerged as an urban centre in the highland valley of Ayacucho at the beginning of the Middle Horizon. Craft specialists soon developed an artistic style that influenced ceramic, textile, metallurgical, and architectural traditions across Peru. No one denies the significant stylistic influence of the Wari, but there is considerable debate on the interactions that peripheral areas had with the Wari urban centre. This debate is fueled in part by a dearth of studies of those areas that were clearly impacted by the spread of Wari ideas and material culture, but do not appear to have fallen under direct Wari control.

In 2004, Justin Jennings began a four year project in one of the areas influenced, but perhaps not controlled, by Wari—the Cotahuasi Valley of Peru. This work has been conducted in collaboration with Willy Yépez Álvarez, the Peruvian director of the project, bioarchaeologist Corina Kellner, paleobotanist Emily Dean, and an international team of students and professional archaeologists. With the valley edges rising in places over 3,500 metres from the valley floor, Cotahuasi is one of the deepest canyons in the world. It is one of the richer natural resource areas in Peru, and boasts large deposits of obsidian, copper, silver, gold, ochre, and rock salt.

Like many regions of Peru, the evidence for Wari influence on the Cotahuasi Valley is unmistakable, but evidence for Wari control is ambiguous. The ceramic and textile traditions in the valley were radically transformed by Wari influence. At the same time, population significantly increased, and there was an increase in agricultural production. Middle Horizon sherds found on many of the terraces suggest that much of the region’s terracing dates to this period. There is also evidence for the increased exploitation of the valley’s natural resources, and data from both ceramic assemblages found at cemeteries and architectural forms at habitation sites suggest the development of social stratification by at least the Middle Horizon.

Tenahaha was an important ritual and funerary centre in Cotahuasi during the Middle Horizon, and contains both architecture and ceramics that exhibit strong Wari influence. It appears to have been critical to the dissemination of Wari culture in the valley, and is also the only site that was abandoned after the Wari state collapsed around 1000 AD (the site was reoccupied 500 years later when the valley came under Inca control). The excavations at Tenahaha were designed to uncover data on ceramic assemblages, diet, mortuary remains, and architecture to use as indicators of interregional relationships.

The 2005 and 2006 field seasons revealed a complex occupation sequence at Collota that includes material from the Late Horizon, or Inca (AD 1470 - 1532), and Early Colonial (AD 1530 - 1570) periods. The 3-hectare site contains a Middle Horizon and Late Horizon domestic sector, a Middle Horizon cemetery, and a Late Horizon and early Colonial domestic sector. While the later material provided interesting opportunities to explore different periods of state expansion into the valley, the Middle Horizon period remained the main focus of the project.

Results of the excavations in the Middle Horizon layers question previous interpretations of the site as an administrative centre of the Wari state. For example, the seven tombs excavated from the period all contain locally made ceramics that are often poor imitations of Wari styles and/or blend local elements with Wari iconography. House forms also follow local tradition, and cuisine choices are neither exotic nor elite.

The results of the excavations at Tenahaha, as well as earlier survey work in the Cotahuasi valley, have been extensively published (see the list of publications on the ROM staff page). A monograph on the Tenahaha excavations was published by the University of Alabama Press in 2015.