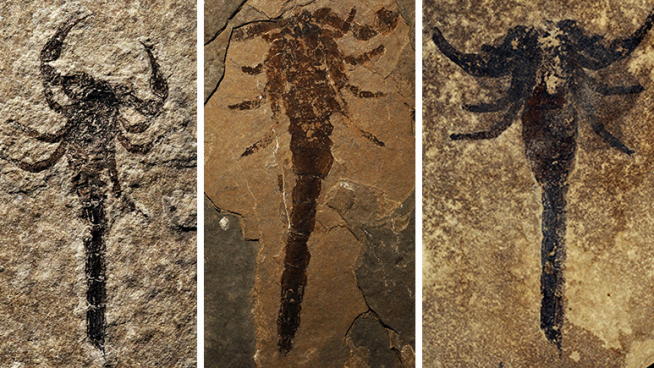

A mid-Silurian aquatic scorpion – one step closer to land?

Rocks of the 430 million year old Eramosa Formation Konservat-Lagerstätte on the Bruce Peninsula have produced an amazing new species of aquatic fossil scorpions, Eramoscorpius brucensis, which contributes to our understanding of how scorpions may eventually have moved from the sea onto land.

Their legs, intriguingly similar to those of a modern scorpion, end in a short foot that could have been placed flat on the ground, providing a weight-bearing surface which, combined with the legs’ sturdy attachment to the body, would have allowed the animal to support its own weight without using the buoyancy of water. This demonstrates that a key prerequisite for living on land – the ability to walk unsupported by water – appeared surprisingly early in the fossil record.

The presence in the same rocks of other fossils of animals that lived only in the sea, and a lack of any other evidence of dry land, indicate that these new scorpions must have spent most of their time under water; however the fossils occur alone on rock surfaces that show ripples suggestive of brief exposure to air. A possible explanation is that the scorpions took advantage of their leg structure to venture briefly into a temporarily exposed area in order to moult and then returned to deeper water. A scorpion sheds its old exoskeleton (shell) by spreading its legs and pincers and then pulling itself out through the front of its old shell. Picture trying to get out of a turtle neck onesie through the neck, without undoing it, by pulling it down over your arms, body and legs. Oh – and it has built in mitts and booties, doesn’t crumple up very well, and you can’t turn it inside out. Having difficulty? For a while you are totally immobilized. Scorpions do this several times in their lifetime. If it could get away from deep water, the vulnerable, and probably tasty, scorpion would have been safe from predators such as large cephalopods and eurypterids, whose remains are also found in the Eramosa Formation. Our scorpions are preserved in a splayed posture suggesting that they represent empty moulted exoskeletons – the discarded, too small shells they left behind - rather than actual carcasses of an animal that died.

The Eramosa scorpions range in size from about 29 to 165 mm long, representing several different age classes. These Ontario specimens are the oldest known scorpions from North America and among the oldest in the world.

Our specimens all hail from the Bruce Peninsula, where the Eramosa Formation Konservat-Lagerstätte has been likened to “Ontario’s Burgess Shale” because of its rich assemblage of superbly preserved remains of soft-bodied organisms normally poorly represented in the fossil record (see also https://www.rom.on.ca/en/blog/a-silurian’shark’tale). The Eramosa is quarried extensively for building and dimension stone, but our fossils have arrived at the ROM in a variety of ways: while several were spotted by quarry workers, one was found in a quarry spoil heap by a young fossil hunter, and others were discovered in quarried stone delivered to landscaping projects far from their origin, destined for patios and garden walls.

The enthusiasm and generosity of amateur fossil collectors brings important specimens to our attention and allows us to study and publish these findings, which are vital to the ROM's collections and research.

The findings form the basis of a paper co-authored with former ROM Assistant Curator Dave Rudkin, and Jason Dunlop, of the Museum für Naturkunde in Berlin and published in the journal Biology Letters.