Safavid Tile Project IV: The Artist behind the Arches

Written by Lisa Golombek, Curator Emeritus (Islamic Art)

In 17th century Iran, unlike earlier times, painters often signed their works. These were individual pages, collected by the connoisseur and bound in an album, or the artist signed pages of an illustrated manuscript. Although these artists may have also designed or painted architectural decoration, no signatures from mural paintings or tile panels are known. Some of the paintings surviving on Safavid palaces, such as the Chehel Sotoun (1647), are significant works of art, but we can only surmise who painted them by comparing them with the signed works on paper. Even then, the style of a great master, such as Riza Abbasi (c. 1565–1635), was emulated by his students and fellows. As some of the mural paintings were done after his death, we know for sure that they were painted by his “school” and not by him.

In order to identify the master of the ROM tile panels, we have to look at the stylistic characteristics of the whole series that we believe belong together and appear to have come from a single palatial building. The series consists solely of tile arches, consistent in size, which share the same palette, figural style, and compositional arrangements. The compositions are complex, often with many figures, but the moving limbs link to form rhythmic lines across the surface.

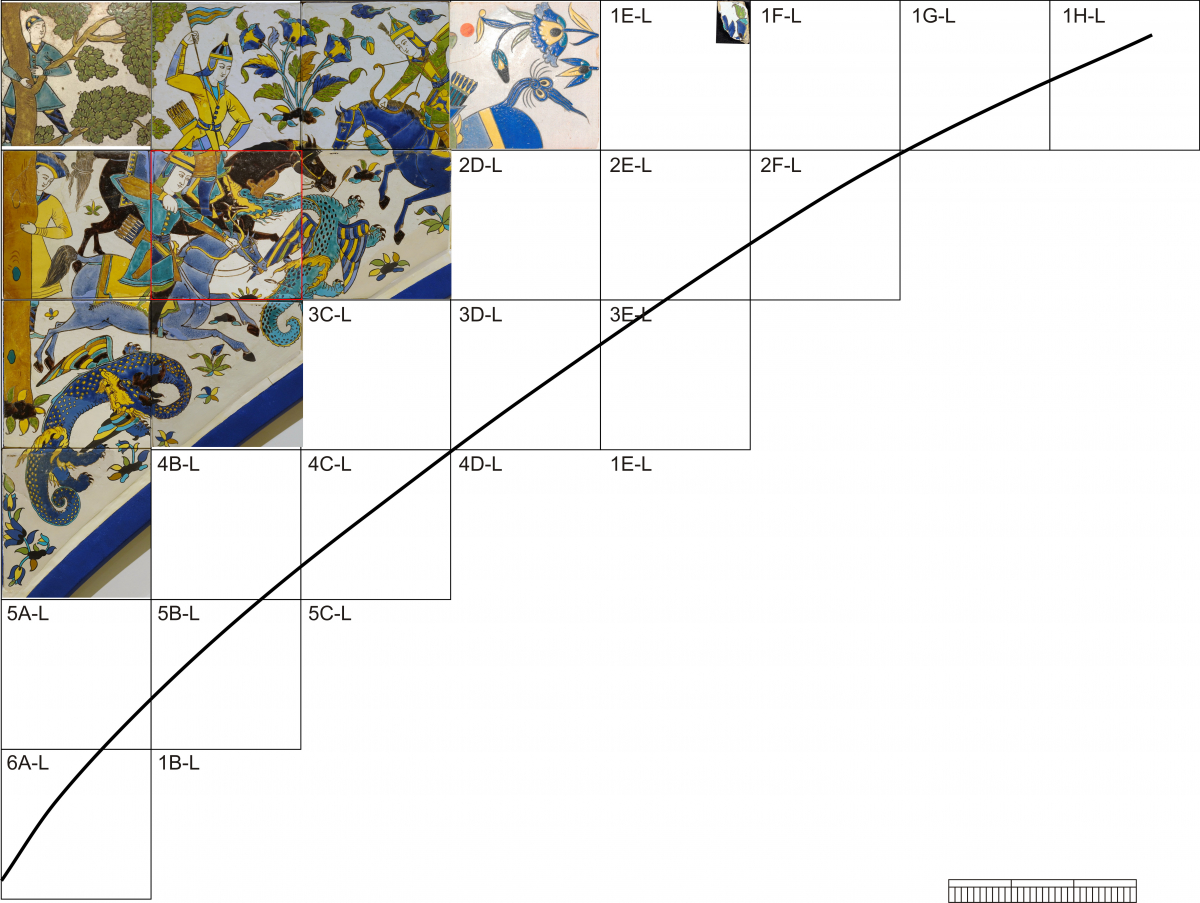

Fig. 1 Dragon Hunt, as reconstructed by Robert Mason, with additional tile in outer corner. Tile Arch, cuerda seca, Isfahan, Iran, c. 1685. Royal Ontario Museum

Looking first at the ROM’s dragon hunt, we see three horsemen, attacking a dragon while a second dragon appears to have been defeated. It is relegated to the triangular space where the arch rises from below. The action is framed along the side of the arch by the tree, and two onlookers direct or view toward the horsemen. The two viewers are static, one hiding behind the tree while the other, a boy, has climbed the tree to safety. The horses gallop, creating movement across the panel. The two warriors who ride with bow tensed, one below near the base of the arch, the other above, tilt toward each other, aiming at the dragon between them. Their bodies, together with the third horseman, form a triangle following the curve of the arch. The straight lines connecting the men, emphasized by the spear thrust by the third horseman, contrast with the energized curling and twisting of the dragons. Although the human figures do not display emotion, this scene is full of tension and drama, from the brave actions of the horsemen, to the fear and trembling evident in the positioning of the two viewers.

A more placid scene is depicted on the ROM’s “Picnic” panel.

Fig. 2. Princely Picnic, displayed in Wirth Gallery of the Middle East. Tile Arch, cuerda seca technique, Isfahan, Iran, c. 1685. Royal Ontario Museum.

Two musicians, sitting cross-legged, anchor the scene at the base of the arch. However, their upward gaze propels our attention toward the apex. In the corner is a group of buildings, probably representing the town, from which this group has escaped to enjoy the countryside. A group of five men is aligned along the curve of the arch. In the middle a servant pours a drink, but our attention is now arrested by a tree, rising from the space between them. On its branch stands a boy, clinging to the tree. He has caught the eyes of the two men before him and of another, who stands above the musicians. They all hold a finger to the mouth, which is a standard gesture of amazement, well known from Persian painting. The main actor in this story appears to be the standing man aiming his bow toward the tree or toward the bird flying in its direction. The robe of the shorter man behind him forms a line with the strung bow that culminates in the boy’s body, thus emphasizing the connection between them and energizing the depicted action. We don’t know exactly what is happening here. Most renditions of aristocratic picnics in Persian painting of this period (and there are many) display no activities other than feasting (and dalliance!) .

Fig. 3 Outdoor entertainment of princess or courtesan, tile panel, cuerda seca technique. Isfahan, Iran, mid- 17th century. Courtesy of the ©Victoria and Albert Museum, London (139;1 to 4-1891)

In our tile panel the archer may be shooting at the bird who is returning to its nest, for fear that the boy is stealing its eggs. Note that there seems to be a “branch” protruding from the boy’s collar. What if it is not part of the tree but a dangerous snake? Might this be an allusion to some folk tale that we don’t yet know? And why are the men wearing “socks” rather than shoes? There is a cast-off shoe at dead centre! So this master has not only created a variation on the traditional picnic theme. He has hidden within it clues to some story or event that we have yet to discover.

A few idiosyncrasies of the tile panels’ style may be useful in identifying the artist although they do not characterize his style. Many of the male faces on the tiles have handlebar mustaches. This fashion was a favorite during the period of the artist Mu’in Musavvir (1630’s-1697), a pupil of Riza Abbasi. The men depicted in both his album pages and manuscript illustrations often wear such mustaches. Another motif shared by the painting with our tiles is the gesture of amazement, frequently seen in Mu’in’s illustrations. A good example is the painting below from a Shahnameh of 1650, signed by Mu’in. The two men behind the hills at the left hold a finger to the mouth in amazement. Almost all of the men in this painting have mustaches. Another characteristic shared by our tiles with the painter Mu’in is the colour palette. He favoured solid areas of luminous colours, such as fuschia, purple, yellow, pink, as one sees here. The technique of cuerda seca found on our tiles (see Blog...) was particularly suited to this bold use of colour. These idioms are found throughout Mu’in’s works on paper, but they would also have appeared in works of his contemporaries who emulated him. However, two tile arches show a more profound relationship to Mu’in’s works on paper. Both arches are in the Hearst Castle, San Simeon, California.

Fig. 4 Shah Isma’il battles his rivals. Tile arch, cuerda seca technique, Isfahan, Iran, c. 1685. Hearst Castle, San Simeon, CA, 529-9-1792. Photograph by Victoria Garagliano/©Hearst Castle®/CA State Parks.

This scene has not been identified, but because it shows two armies confronting one another wearing different headgear, it is likely to be a specific event. The army closest to the apex wear turbans, while their opponents have helmets. This is how battle scenes in manuscripts of the History of Shah Isma’il are depicted according to my colleague Eleanor Sims. The army of the Shah Isma’il wear the turbans.

Fig. 5 Shah Isma’il Defeating Amir Husayn and Murad Beg. From the Tarikh- Jahan gusha’i-yi khaqan-i sahib-i qiran. Worcester Art Museum, Worceser, MA. Acc. No. #R1962.179. Isfahan, Iran, c. 1688.

Shah Isma’il was the founder of the Safavid dynasty and is considered to have been divinely guided. At the age of twelve he began to assemble followers who, after many ups and downs, defeated the ruling Turkman dynasty. Stories about his life and struggles leading to the founding of the Safavid dynasty were collected and recorded during the early 17th century. According to A.H. Morton these stories were compiled around 1676 by a certain Bijan. At least three manuscripts with illustrations of these tales survive. In this painting Shah Isma’il (fig. 5), who is often shown as a young man without a beard, is on the right with his army chasing after his opponent, Amir Chulavi, an event that took place in 1504.

It is remarkable that all of the illustrated histories of Shah Isma’il date to the late Safavid period, that is, over 150 years after his death. The notion that these manuscripts represent an unexplained revival of interest in the founder of the dynasty is supported by the appearance of a scene inspired by the manuscripts on the tile panel. Charles Melville suggests that the Safavids valued the heroic and charismatic qualities of Shah Isma’il as exhibited in these tales, making their ancestor an equal to the traditional heroes of Iran, celebrated in the Shahnameh. As in the painting shown here, the army of Shah Isma’il wear the Qizilbash turban (the turban is wrapped around a red cap with protruding cone). Shah Isma’il rides a dappled horse and wields a sword to combat an army that appears to outnumber him. Notable is the use of a musket by the horseman behind Shah Isma’il, as firearms were just beginning to come into use at this time. Already one of his followers has been slain. He is being trampled, while his horse has been upturned! The positioning of the upturned horse in the triangle at the base of this arch may be compared with the placement of the conquered dragon on the ROM arch.

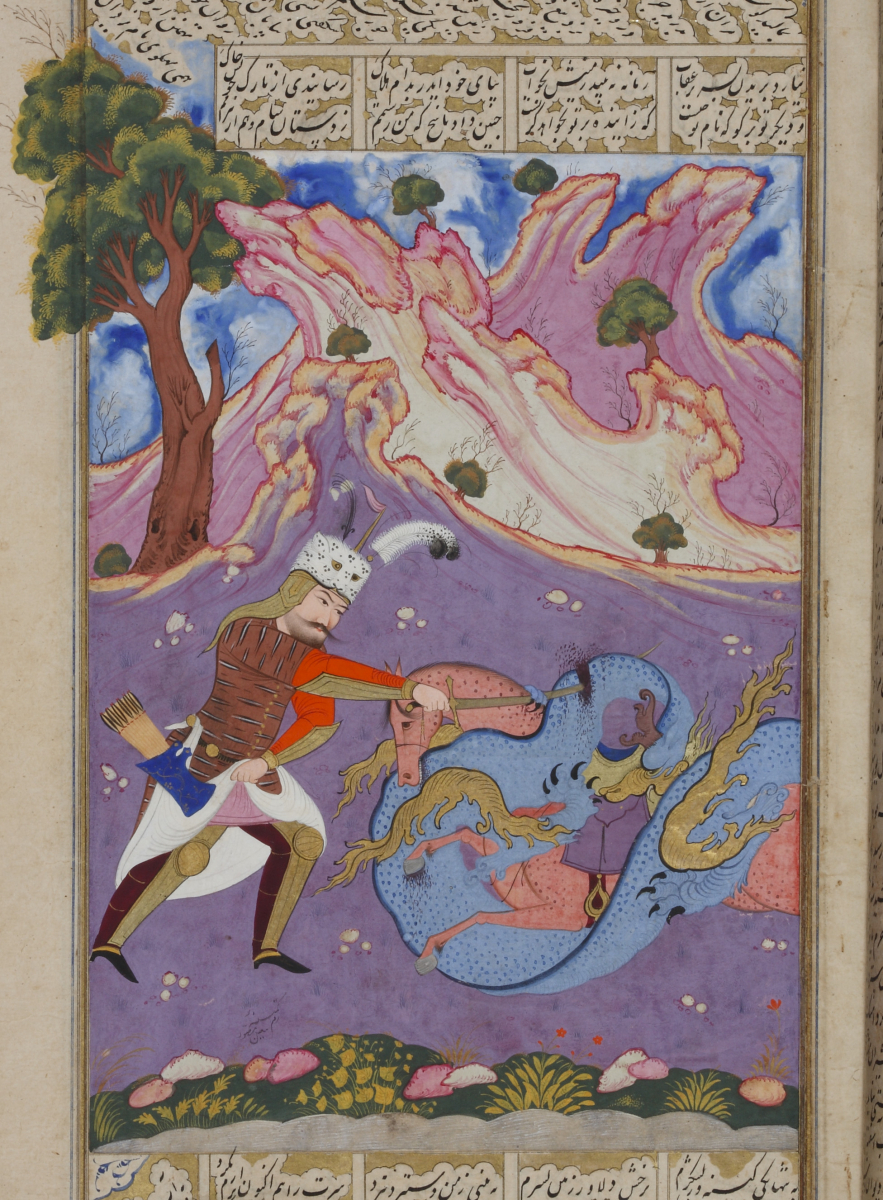

The upturned horse is an unusual motif and catches our attention. We can see a similar dramatic twist in a page from the Shahnameh page painted by Mu’in.

Fig. 6 Rustam overturns Chinghish. From a Shahnameh, Yazd or Isfahan, 1650. Signed by Mu’in Musavvir. The David Collection, Copenhagen, #217/2006, fol. 109b. Photograph by Pernille Klemp.

On this page the hero Rustam has caught Chinghish’s horse by the tail. Chinghish is falling to the ground, where Rustam will behead him. Chinghish was a soldier in the army of the Khan of China. He challenged Rustam to avenge the death of a comrade. Sheila Canby remarked in an article about this manuscript that the more common illustration of this story shows Rustam grabbing the horse’s tail and chasing after him. Mu’in illustrated seven manuscripts of the Shahnameh . Canby considers the moment chosen by Mu’in here to be “utterly novel”. The upside-down horse catches our eye. The circle formed by Rustam’s arms with those of Chinghish, completed by the body of the upturned horse, is a choreography that recalls some of the more complex compositions of the tile arch panels. Mu’in himself may have felt that this was a tour de force. He signed almost all the paintings in this manuscript, but in the margin below this one he added the unique comment: “If there has been any shortcoming, let it be forgiven.” The upturned horse must have won accolades, as it appears on the tile arch panel (Fig. 4).

A second tile arch at the Hearst Castle contrasts sharply with the battle scene.

Fig. 7 Hero fights dragon attacking horse. Tile arch, cuerda seca technique, Isfahan, Iran, c. 1685. Hearst Castle, San Simeon, CA, 529-9-1788. Photograph by Victoria Garagliano/©Hearst Castle®/CA State Parks.

There is only one main actor, the horseman fighting a dragon which has wrapped itself around the horse. Two young persons have taken refuge in the tree at the center of the arch. The blending of the horseman’s raised arm with the circle formed by the dragon infuses this image with energy. The dragon’s tail tightens the circle around the horse’s hind legs. This composition appears inspired by the work of Mu’in as seen in an illustration to the story of Rustam and his horse fending off a dragon. The artist Mu’in seems to have loved the challenge to entangle man and beast. In the tile panel even the two onlookers appear wrapped in the branches of the tree. This panel was clearly designed in the spirit of Mu’in, if not by the artist himself.

Fig. 8 Rustam kills the Dragon with the help of his horse Rakhsh. From a Shahnameh, Yazd or Isfahan, 1650. Signed by Mu’in Musavvir. The David Collection, Copenhagen, #217/2006, fol. 44a. Photograph by Pernille Klemp.

Finally, another characteristic that our tile panels share with the paintings of Mu’in is the attention paid to the faces.

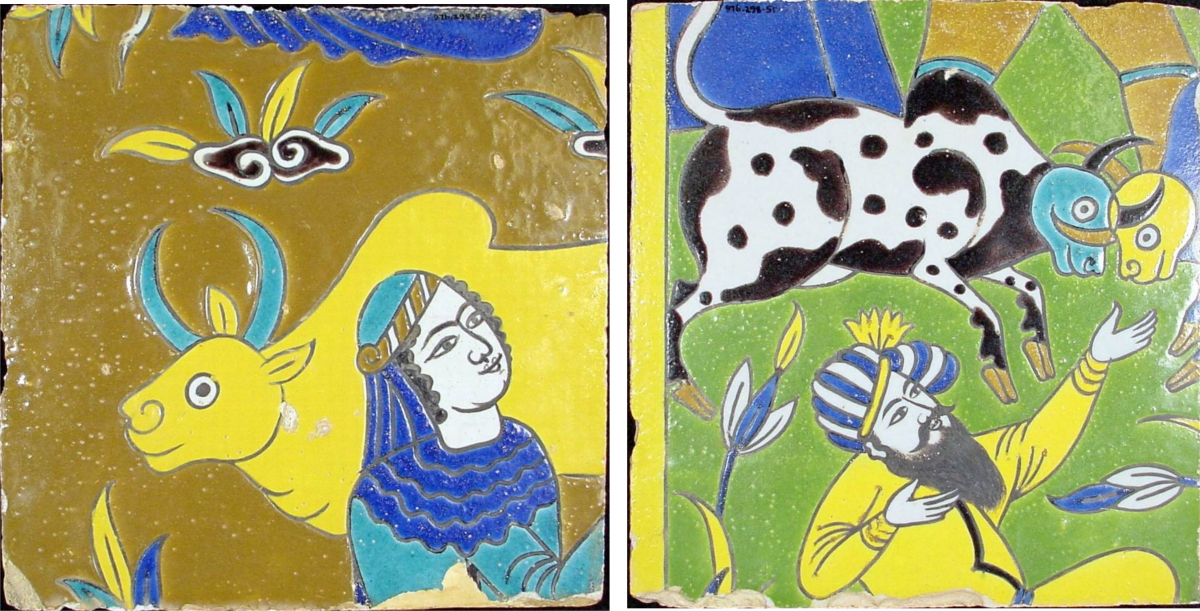

Fig. 9 Woman milking zebu, and Butting zebus watched by bearded man. Tile, cuerda seca technique, Isfahan, c. 1680. Royal Ontario Museum.

On the tiles the faces do not express a specific emotion but are rendered in fine brushstrokes that endow them with a certain gravity and beauty. The details were done after the coloured glazes had been fired. They are painted over the mat white glaze that underlies the entire tile. The area for the face was left uncoloured, to be completed at the end. It is probably at this point that a master such as Mu’in would have put his hand to the tile. The expression of drama and emotion is not to be found in these beautiful faces but instead, in the movement suggested by the bodies. They pulsate and convey excitement, wonder, or some other relevant feeling. This is precisely what we see in Mu’in’s paintings. Massumeh Farhad, Curator of Islamic Art at the Sackler Gallery, Washington, points to Mu’in’s use of “poses and gestures” to create tension. While we cannot be certain that this master was himself responsible for adorning the arcades of the palace garden with brilliant tiles, his influence is clearly there. Perhaps he had a hand in applying the finishing touches.

LINKS:

Safavid Tile Project I: The Technology

Safavid Tile Project II: Rebuilding the Friezes

Safavid Tile Arch Project III: The Palace of the Stables

Wirth Gallery of the Middle East

Moʿin Moṣavver at persianpainting.net

Further Reading:

Sheila R. Canby, “An Illustrated Shahnama of 1650: Isfahan in the Service of Yazd,” Journal of the David Collection, 3 (2010):54–113.

Robert Eng, on the painter Mu’in Musavvir’s illustrations to the histories of Shah Isma’il: http://www.persianpainting.net/moin_ms_index.html)

Massumeh Farhad, “The Art of Mu’in Musavvir: A Mirror of his Times,” in Sheila R. Canby (ed.) Persian Masters: Five Centuries of Persian Painting, Bombay, Marg Publications, 1990:113–28.

Lisa Golombek and Robert B. Mason, “The Garden of the Pavillion of the Stables, Isfahan,” Orientations, 50/2 (2019): 124–33.

Charles Melville, “The Illustration of History in Safavid Manuscript Painting,” in Colin P. Mitchell, New Perspectives on Safavid Iran: Empire and Society, New York, Routledge, 2011: 163–97.

A.H. Morton, “The Date and Attribution of the Ross Anonymous. Notes on a Persian History of Shāh Ismā`il I,” in C. Melville (ed.), Persian and Islamic Studies in Honour of P.W. Avery, Pembroke Papers, 1990, Vol. 1: 179–212.

Eleanor Sims, “A Dispersed Late-Safavid Copy of Tārīkh-i Jahāngushā-yi Khāqān-i ṣāḥibqirān,” in S.R. Canby, Safavid Art and Architecture, London, British Museum Press, 2002: 54–57.